Below is a range of general information on Selective Mutism, in three sections:

You can:

- view the documents in the preview panes, or

- click Open to view the document at larger size in a new page, or

- click to Download the document (as a pdf to your computer) for printing or sharing via email.

SMIRA Leaflets

—

Where to Get Help with Selective Mutism

Registered Charity No. 1022673

The information charts below are particularly relevant for England and Wales (UK) but contain general points which may be useful elsewhere.

NB: Page 4 below contains a glossary of abbreviations

The links shown on the flowcharts are given in clickable form underneath each flowchart

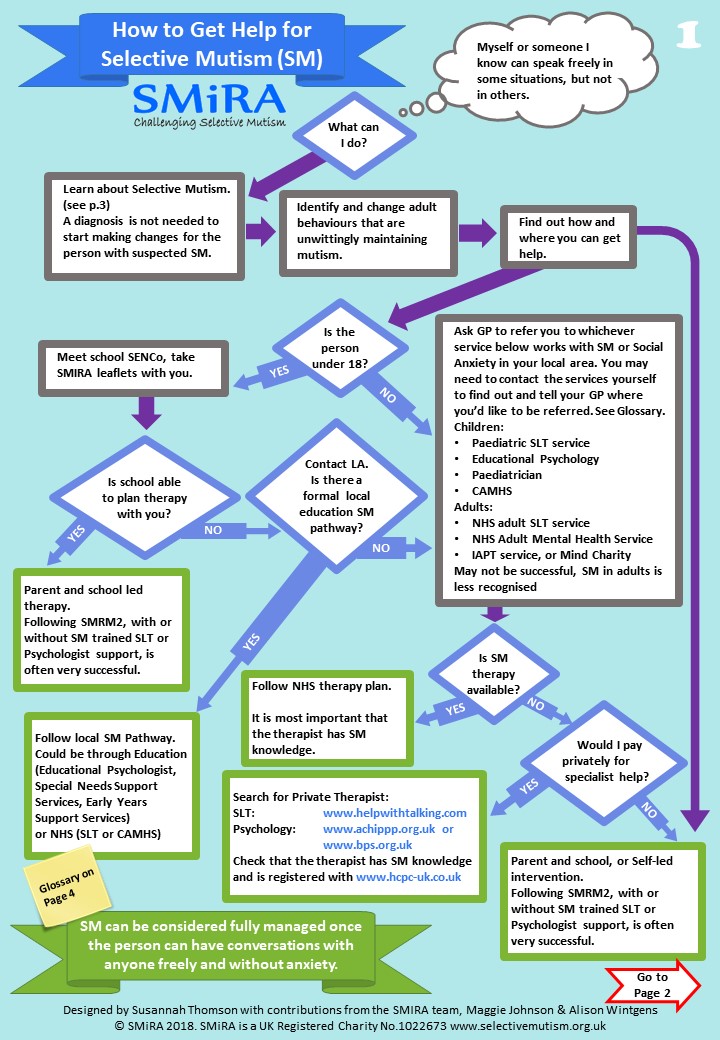

1. How to get help for Selective Mutism

Links given on page 1 above:

Search for Private Therapist

- Speech & Language Therapy: www.asltip.com – in the ‘Services Offered’ section, tick the Selective Mutism box. In the ‘Distance’ section, you can extend the distance as support can be done remotely for you

- Psychology: www.achippp.org.uk or www.bps.org.uk

Check that the therapist has SM knowledge and is registered with www.hcpc-uk.co.uk

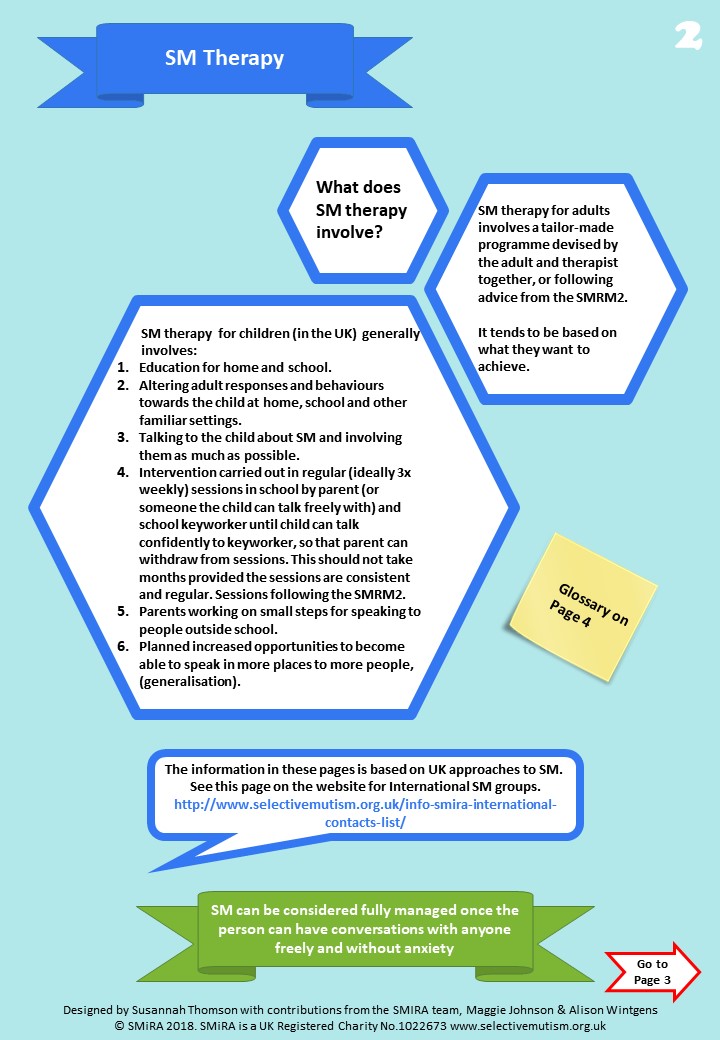

2. Selective Mutism Therapy

Links given on page 2 above:

SMIRA International Contacts List

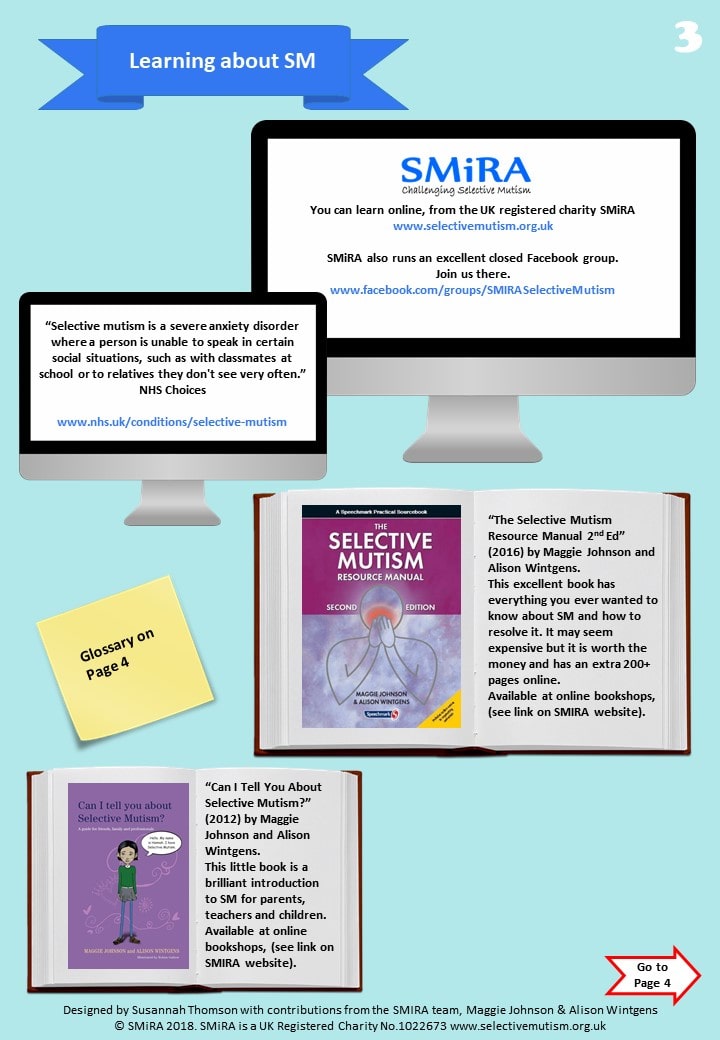

3. Learning About Selective Mutism

Links given on page 3 above:

- Learn online, from the Information section on this website

- Join the SMIRA Facebook Group (it’s a closed group so there may be a short wait while we approve your membership request.)

- See NHS Choices – Selective Mutism

Additional Reading

Details and purchase links for all of the books below are on the Books page on this website.

- “Selective Mutism Resource Manual 2nd Edition” (Johnson & Wintgens). Most changes in 2nd Edition are for older people with SM and generalising outside school

- “Tackling Selective Mutism” (Sluckin & Smith, ISBN-13: 978-1849053938, ISBN-10: 1849053936)

- “Can I tell you about Selective Mutism?” (Johnson & Wintgens, ISBN-13: 978-1849052894, ISBN10: 1849052891)

- “Can’t Talk? Want to Talk!” (Jo Levett, ISBN-10: 1909301310,ISBN-13: 978-1909301313)

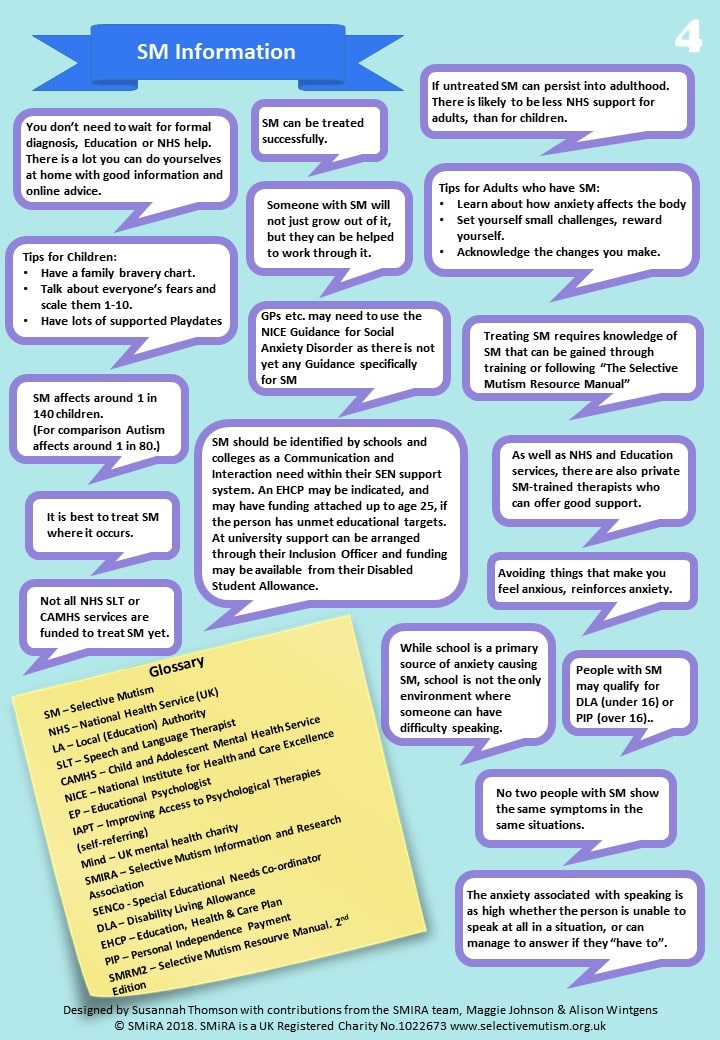

4. Selective Mutism Information

You may download these flowcharts to your computer as a PDF file, for emailing or printing out:

SM Awareness Leaflet (A4)

What Does Selective Mutism Mean?

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

What does Selective Mutism mean?

The following article was written by a parent in an attempt to increase understanding of her daughter’s condition amongst her peers:

If someone uses a hearing aid, you know they have trouble hearing you. If someone else uses a wheelchair, you know they have difficulty in walking. A person who stammers can have problems in saying what he or she really wants. These people have disabilities – selective mutism is a type of disability too, but it is one which can be very hard for other people to understand.

However, many of us can think of something which frightens us or makes us feel extremely uncomfortable. We might not always like to admit it – maybe other people would laugh at us, or say that we were being silly, but to us, that fear is very real. We might be terrified of spiders and be unable to go in a room where we knew one was. Some people are scared of heights, of flying, of confined spaces, of water, of dogs, or even cats. They may go to great lengths to avoid getting themselves into situations where they might have to confront the thing which frightens them. We call these fears phobias.

Try to imagine yourself in the sort of situation which might make you feel anxious. What happens? Your heart-rate can increase, you may sweat, get breathless, feel sick, perhaps blush – perhaps your lips or hands or legs start to quiver or shake? Your brain has received signals of potential danger and has begun to set off a series of reactions that will help you to protect yourself.

A person who suffers from selective mutism has a phobia too. They can speak normally and they want to speak but they often fail to speak. They behave in a completely normal way when they are in an environment in which they feel relaxed and comfortable. In their own home, for instance, they are quite likely to be very talkative, loud, funny and even bossy.

In most other settings, however, including school – they will feel real fear, just as if they are permanently “on stage”. This feeling will be made worse by the knowledge that someone will be expecting them to speak. The words just won’t come out, or else they will come out in a whisper. It may seem like shyness, but it is very different, and the affected person is not necessarily shy. People who have been able to look back and describe their feelings at these times, have talked about their throats feeling tight or paralysed.

It is not so surprising then, that sufferers will try to protect themselves from these unpleasant feelings. They may try to communicate in other ways, with nods or shakes of the head, for example. They are very sensitive to how others see them and are easily hurt. They are afraid of seeming different, or being mocked, or criticised or rejected, and more than anything, they do not want anyone to know they are afraid.

What happens then is that they start to avoid activities which they would genuinely like to take part in. They know that speaking leads to acceptance and to making friends, but speaking, and especially starting a conversation, is incredibly difficult for them. They avoid speaking by withdrawing from people and isolating themselves. This means that they do not really learn how to socialise with other people. They become very lonely, even though they are not loners. They may protect themselves by pretending, and even believing, that they did not want these things in the first place.

Some facts:

Selective mutism was once thought to be very rare, but the incidence is said to be almost identical to the rate of narrowly defined autism.

It is more common in girls than in boys.

No single cause has been established, though emotional, psychological and social factors may influence its development.

Children with selective mutism are likely to…

- Find it difficult to look at you when they are anxious – they may turn their heads away and seem to ignore you. You might think that they are being unfriendly, but they are not – they just do not know how to respond.

- Not smile, or look blank or expressionless when anxious – in school, they will be feeling anxious most of the time and this is why it is hard for them to smile, laugh or show their true feelings, even when they have a wicked sense of humour.

- Move stiffly or awkwardly when anxious, or if they think that they are being watched.

- Find it incredibly difficult to answer the register, or to say hello, goodbye or thank-you – this can seem rude or hurtful, but it is not intentional.

- Be slow to respond – in any way – to a question.

- Worry more than other people.

- Be very sensitive to noise or touch or crowds.

- Be intelligent, perceptive and inquisitive.

- Be very sensitive to the thoughts and feelings of others.

- Find it difficult to express their own feelings.

- Have good powers of concentration.

References:

Robert Goodman & Stephen Scott. Child Psychiatry, Blackwell Science 1997.

Maggie Johnson & Alison Wintgens (2001) The Selective Mutism Resource Manual.

Speechmark Publishing Ltd. Telford Road, Bicester Oxon. OX26 4LQ. (Second Edition published 2016)

© J.Teece/AS/SMIRA/2003

www.selectivemutism.org.uk

Suggestions for Intervention

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

Suggestions for Intervention for Selective Mutism in Children

The Selective Mutism Information and Research Association (SMIRA) has put forward the following suggestions for health professionals and families:

-

- Assessment: because some SM children suffer from other communication disorders that can easily be missed, a Speech and Language Therapist’s assessment should be requested. This can be managed by a home visit or use of recordings if necessary. A psychologist’s assessment is also advisable, but intervention should begin at once.

An experience all too commonly reported, is that children are moved around from one waiting list to another, without actually receiving the help they need.

- Early diagnosis and treatment is important. It is unhelpful to ‘wait and see’ as this could lead to entrenchment and possibly longer term problems. The ability to speak in some situations, but not in others, indicates Selective Mutism.

- Parents and carers must be provided with support and up to date information such as that provided by the SMIRA helpline or its handouts and website.

- All pressure to speak must be removed by all those with contact with the child.

- Offering help at a very young age through an informal play approach has the best chance of success. This usually takes the form of facilitated noisy play during which confidence is instilled and trust is built; adults make mistakes which children become eager to ‘correct’ and uninhibited laughter is generally encouraged. Interaction with animals can also help.

- Older children have been shown to respond well to a very gradual ‘step by step‘ desensitisation approach based in the behaviourist tradition. (Trained professionals from several disciplines, as well as teaching assistants have been able to deliver this.)

- A small minority of SM children will need specialized services such as CAMHS, as their problems are complex and their environment may be problematic. This is sometimes combined with formal CBT. It should be noted however, that unusually minute and gradual steps in the behavioural aspect of treatment are required if the actual speech behaviour is to be changed. Broad, general recommendations are not effective.

- The possible role of medication requires careful thought and is currently used more in the US than in the UK. It is discussed by a Child Psychiatrist in Smith and Sluckin 2015 pp 131-137.

Information and Support

Selective Mutism Information and Research Association (SMIRA) Reg Charity No.1022673.is a national UK support group based in Leicester. It also has overseas links.

It deals mostly with children and parents and has a ‘facebook’ membership of over 3000. It is in touch with many of the leading specialists in the field of Selective Mutism (SM).

www.selectivemutism.org.uk

Email: info@selectivemutism.co.uk

Phone: 0800 2289765

Facebook: Smira – Selective Mutism

There is a completely separate support group for SM adults:

www.ispeak.org.uk or email carl@ispeak.org.uk

Books

Tackling Selective Mutism: A Guide for Professionals and Parents

Benita Rae Smith and Alice Sluckin Eds. 2015

Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London and Philadelphia

ISBN 978 1 84905 393 8 paperback, 308p, £19.99 (royalties to charity)

The Selective Mutism Resource Manual (2nd Edition) Johnson, Maggie and Wintgens, Alison (2016) Speechmark, Bicester, Oxfordshire:

Can I tell you about Selective Mutism? A guide for friends, family and professionals

Johnson, Maggie and Wintgens, Alison (2012) Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London.

Selective Mutism. An assessment and Intervention Guide for Therapists, Educators and Parents

Kotrba, Aimee (2015)

PESI Publishing and Media. Eau Claire, Wisconsin:

Helping your Child with Selective Mutism

McHolm, Angela E., Cunningham, Charles E. and Vanier, Melanie K. (2005) New Harbinger Publications, Inc., Oakland, CA

The Selective Mutism Treatment Guide: For Parents, Teachers and Therapists. Still Waters Run Deep

Perednick, Ruth (2011) Jerusalem. Oaklands

Helping Your Anxious Child

Ronald M. Rapee. 2nd Edition 2009

New Harbinger Press

Also Recommended:

Silent Children – approaches to Selective Mutism – Book & DVD

Edited by Rosemary Sage & Alice Sluckin (2004),

University of Leicester

(Available to purchase from SMIRA)

Exam Guidance

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

Guidance for Special Arrangements and Exemptions from School Exams

One question that comes up frequently, with relation to SM, is how can someone with SM (an anxiety disorder) better handle exams, particularly an oral examination either in their mother tongue or in a second language.

The following advice is written primarily for the UK education system but contains information that might be useful in other countries and education systems.

Introduction

Everybody handles anxiety in a different way. We know that people with SM find some situations highly stressful and examinations are just one of those causes, or triggers, which can generate high levels of anxiety. This is commonly visible as what is known as a ’freeze’, which renders the person incapable of completing the examination in a normal fashion, in the normally allotted time, or with the expected results. Oral examinations, where speech is required can often be impossible for someone with SM.

We hear of some students who are deducted marks from their score for ‘failure’ at the oral stage, even where the failure is not due to lack of knowledge. We hear of others who obtain agreed adjustments to exempt them from such examinations and we hear of those who obtain agreement to sit the oral examination under special conditions such as ‘with a parent’ or ‘using a recording device’.

What we are looking for are reasonable adjustments to the normal examination procedure for those who usually struggle with that, and have a justifiable reason for needing an adjustment. Common sense is probably not considered as ‘justifiable’ but should be applied. The procedures are looking for documented evidence of the reasons why someone should receive an adjustment. It’s a formal process. It needs time, and it needs planning. Clearly this situation needs managing in advance and we hope that this document gives some useful advice.

© Copyright 2016 SMIRA

UK Regulations and Guidance

The adjustments available for external exams (e.g. GCSE, GCE AS & A Levels & vocational qualifications) are called ‘Access Arrangements’ and there is a deadline by which schools have to apply for them. This deadline depends on when the exam is due to be taken, and is likely to be several months in advance of the exam, e.g. a date in March is common for June GCSE exams. For this reason it is sensible to make enquiries about Access Arrangements with the school at the start of any exam course to allow plenty of time to discuss the needs of the student, for the school to do the administration required and to allow evidence to be collected to support the application.

The following links to the Joint Council for Qualifications (for Key Stages 4 & 5) and the Standards and Testing Agency (for Key Stages 1 & 2) give advice on how to go about getting such adjustments to an exam.

Joint Council for Qualifications – Access Arrangements and Special Consideration

www.gov.uk – Key Stage 1 – 2017 Assessment and Reporting Arrangements (ARA)

www.gov.co.uk – Key Stage 1 tests: how to use access arrangements

www.gov.uk – Key Stage 2 – 2017 Assessment and Reporting Arrangements (ARA)

gov.co.uk – Key Stage 2 tests: how to use access arrangements

General Advice

Education establishments, schools, academies, colleges and universities all have processes and procedures for dealing with examinations and will also have procedures for dealing with special cases. Parents and students should approach the establishment to discuss what processes exist and what the specific procedures are.

Usually it would be the establishment that carries out the procedural work, contacting the authorities to gain approvals for adjustments. Parents and students would provide the justification required by the procedures (e.g. may need medical reports).

- The establishment may need to get permission for a student to have extra time for the exam;

© Copyright 2016 SMIRA

- For special equipment in exams e.g. the use of a laptop, the establishment will have to show proof that the student usually uses one in class i.e. it is their ‘normal way of working’. Some SM people find a laptop easier for exams as they may physically freeze and find it difficult to write manually when anxious, and they can rewrite things if they are not happy with them, thus relieving some of their anxiety. If you think a laptop would help then get the school to either provide a laptop or provide your own but insist they allow it to be used for lessons from the start of the exam course – they can then honestly state that it is the student’s normal way of working in lessons;

- Schools can provide some access arrangements without having to ask the exam board first, such as a separate room (with invigilator) & timeouts;

- Think about using recording devices, video, etc. where they don’t themselves raise anxiety;

- Use common sense.

… and finally

Education establishments may be reluctant to go through the procedure, as it requires them providing documentary evidence that the student needs them and takes time.

Don’t let them fob you off! Parents and students can successfully guide the establishment to what they want them to arrange.

© Copyright 2016 SMIRA

Appendix

Other Links

Home-Educated Students: ehe-sen.org.uk/exams

Other Needs

driveryouthtrust.com

Glossary

SM – Selective Mutism

Bibliography

None for this document.

Please refer to the SMIRA bibliography published on the www.selectivemutism.org.uk site.

Disclaimer

SMIRA is not responsible for the content of external websites. Websites are subject to change at any time by their owners.

Advice

for Sports Coaches & Extra-Curricular Providers

Children with SM often find it hard to pursue hobbies and interests because of the expectations to talk, but that shouldn’t prevent them from being accepted and being able to have a go. Many children with SM are creative and enjoy activities such as dance, drama and sport. They just need the right adults around to support and encourage them.

Below is a link to a document with information on how to support children with sports and extra-curricular activities:

Advice

for Sports Coaches & Extra-Curricular Providers

NHS (UK) Selective Mutism

Below is a link to the UK National Health Service (NHS) guidelines on Selective Mutism:

SMIRA’s Global Links

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

SMIRA International Contacts List

(Click the ‘Open’ button below for the list)

SMIRA is happy to provide links to SM support organisations around the world. These are grouped by language rather than by country.

The links referenced in this list are provided for informational purposes only. SMIRA is not responsible for the content of external websites. The internet contains other sites, some of which are out of date, others are dead links. These have been omitted from this list. If you are aware of errors in this list of any other association, please advise SMIRA so that the list can be updated.

Contact: info@selectivemutism.org.uk

Advice to Parents and Carers during COVID 19

We at SMiRA – many of whom have family members who have SM ourselves – know that it is very hard to juggle all that is expected of us in terms of our own work, home schooling and so on. We can only do what we can do. So we want to say – if you can only focus on one thing with your SM youngsters during this lockdown period it would be to prevent them from withdrawing completely to the small comfort zone of home.

Returning to School After Lockdown:

Here is an additional document with regard to returning to school after lockdown:

Open Download

Leaflets from the Selective Mutism Resource Manual (2nd Edition)

—

Video chat – small steps

We are posting this link to Maggie Johnson’s resource at the top as it is especially relevant for online therapy at the moment:

Quiet Child or SM?

Do’s and Don’ts at Pre and Primary School

Do’s and Don’ts at Secondary School

Maintaining Factors

Helping Children Cope with Anxiety

What to Say When

Talking in Public Places

Older Children and Teens

The Older Child or Teen with Selective Mutism

Ricki Blau

Selective Mutism in the Older Child

Selective Mutism (SM) is usually noticed when a child begins pre-school or kindergarten, if not before. So when a student in the upper elementary or secondary grades has SM, it’s safe to assume that he or she has been living with Selective Mutism for many years. Within the lifetime of today’s teens, researchers and treating professionals have learned much about this anxiety condition. Young children who receive prompt and appropriate treatment now make great strides. But information about SM is still not as widely available as it should be—educators, doctors, and psychologists often fail to recognize SM or understand how to help affected children. Consequently, many children do not receive early diagnosis or appropriate support.

Older students with SM may have received no treatment or may have suffered years of inappropriate treatment and negative reinforcement. Instead of being helped to control their anxiety and become more comfortable at school, they may have been pressured to do the things they feared, such as speaking. Over the years they have developed ingrained behavior patterns and maladaptive coping mechanisms by which they avoid situations that make them anxious. Not speaking has become a habit that is difficult to break. They begin to see themselves as “the kid who doesn’t speak” as do many people around them. The fear of receiving attention if they should start to speak makes it harder to imagine changing. They may also have developed phobias about speaking or having their voice heard. Older children with SM often lag behind their age peers in social competence because they’ve had less experience with peers and adults. Treatment plans for the older child must take these complications into account. 1

Students with SM are, in general, extremely sensitive individuals. Older children and teens are acutely aware of their differences and the responses they elicit from their teachers and other adults. People have been trying to get them to talk for years! They understand that they repeatedly fail to meet standard expectations in the school setting. Consequently, they are wary and keenly aware of the most subtle pressure to communicate. Wanting to avoid attention, they typically have learned to hide the appearance of anxiety; while younger children may freeze and show a blank expression, older students more commonly appear relaxed and “ok,” even when they’re not.

In summary, older children have developed more complicated profiles, influenced by their experiences and environmental stressors. Their individual profiles tend to show more variation than with younger children, and treatment needs to be tailored to the individual.

Helping the Student Make Progress

For all of the above reasons, you can expect progress to be more difficult and slow once a child has reached the age of eight or nine. Different strategies and interventions are needed for older children or teens. Consider, for instance, a fading strategy, in which a child first talks with a parent in a private room at school, and over time other individuals are gradually drawn into the conversational group. This often succeeds with a very young child. Older children, on the other hand, have developed a self-image as a noncommunicator and would recognize the situation as a set up aimed at getting them to talk.

The fading strategy doesn’t work for them. As experienced treating professionals have found, the older child or teen needs to be actively involved and in control of their therapy, which aims to help them recognize their anxiety and take small, controlled steps in real life situations. In younger children, medication to reduce the anxiety often produces quick and dramatic results. With older students who have many habits to unlearn, medication is often an important adjunct to behavioral therapy but many treating professionals have found that it not as effective on its own.

For older children, the thought of changing longstanding habits and exposing themselves to anxiety-provoking situations is frightening, and they can become quite resistant to therapy. Dr. Elisa Shipon-Blum, the Medical Director of the Selective Mutism Group/Childhood Anxiety Network, has observed that if a child is not verbal in school by the age of eight or nine, he or she is unlikely to talk at school until at least high school, and possibly later. For students in this age range, she has suggested that the emphasis be on helping the student realize his or her academic potential and remain socially connected. This will usually require flexibility about assessment and participation.

The student’s self-consciousness usually extends to situations beyond speaking and commonly affects non-verbal as well as verbal communication. In general, the student with SM finds it much easier to respond to another individual than to initiate communication. A student who is able to respond to a teacher’s question, (verbally, in writing, or with a gesture) may be unable to initiate with that same teacher to ask a question or contribute to a class discussion. He or she may be unable to take a note to the attendance office, check out a library book, or make a purchase at the snack bar. SM has an impact both academically and socially, and students can feel left out because of their inability to interact with ease.

If teachers can help decrease anxiety at school and increase the student’s self-confidence, there will be a greater chance of progressing communicatively, both non-verbally and verbally. Perhaps the student will interact with new work partners, carry notes to the office without a friend, or respond more easily, in writing, to discussion questions. It is important to recognize even small improvements and not become discouraged! Measure success by how well the student functions at school in general, and not by his or her communicative relationship with the teacher. Even the most empathetic and skilled teacher is an authority figure, and students with SM are commonly more inhibited with teacher than with other people. At the beginning of a new school year, new teachers should start allow for plenty of “warm-up” time. Start slowly with the goals of getting to know the student, gaining their trust, and helping the student become as comfortable as possible at school. Emphasizing or pushing for communication in any form, non-verbal, written, or oral, is likely to cause the student to withdraw. Communication will develop as the student becomes less anxious.

Helping the student make and maintain social ties is vital. It is, unfortunately, too easy for a socially anxious individual to become isolated and depressed. Depression is more likely as a child enters adolescence and can lead to more severe anxiety, social isolation, lower performance in school, suicidal thoughts, and self-medication with alcohol or drugs.

It’s More than Not Talking

Studies have shown that over 90% of children with SM have Social Anxiety Disorder, also known as Social Phobia. 2 3 4 5

In fact, some experts have suggested that SM may be a manifestation or variant of social anxiety. These students are excessively selfconscious. They are afraid of being embarrassed, judged or criticized, and of receiving scrutiny or attention. 6

Social anxiety does not make a child anti-social or even asocial. A socially anxious child can be very social and enjoy the company of family and friends when in a familiar and comfortable setting. Many students are more comfortable with their peers (this is more common), but others are more comfortable with a trusted adult.

Some students, who may have partially overcome their SM, do speak at school. Most likely, these students still experience anxiety, even though it is less obvious. 7 8

They may not be able to speak in all situations or with all people. A student who is able to respond to a teacher’s question or even contribute to a discussion may be completely unable to ask a question or express a concern.

Anxiety can affect academic performance in many ways, even in a student who begins to talk at school. Not talking is only the tip of the iceberg! Other manifestations of anxiety include:

- Perfectionism; worry that work is inadequate in quality and/or quantity

- Procrastination and avoidance

- Problems with test-taking and timed testing; may rush for fear of not finishing in

time; may panic; may be too anxious to check answers or may check answers repeatedly and not finish - Problems with open-ended or unclear assignments; worry that they don’t know what the teacher wants or that they will do the wrong thing

- Unable to ask for help or clarification; unable to express worries or complaints

- Afraid to express an opinion, even to express likes or dislikes

- “Blanking,” or panic-like reactions

- Easily frustrated

- Illegible, tiny, or faint writing to obscure answers they’re unsure of

- Difficulties with group work; may be unassertive or passive; conversely, may be a “control-freak” if worried that the group’s work is inadequate

- School refusal or faked illness to avoid social situations at school or because of worries about schoolwork

The first step in helping a student with these difficulties is to recognize that they are manifestations of anxiety. The student is not choosing to behave this way and is neither unmotivated nor oppositional. Then,

- work to build the student’s self-esteem and self-confidence,

- increase the student’s comfort and reduce anxiety at school,

- back off on all pressure to speak, and

- make accommodations, such as those suggested in the following section, that allow the student to progress academically.

Mild expressive language difficulties may be more common in students with SM, and they can be a source of added self-consciousness and anxiety.9 10 Subtle effects on oral and written expression can include: word retrieval glitches, terse writing with few descriptive details, and the use of non-specific language (e.g. “that thing” instead of a precise noun). A screening by a Speech and Language Pathologist or Neuropsychologist may be appropriate if there are concerns about language difficulties.

Accommodations and Classroom Strategies

Listed below are suggestions for strategies and accommodations that may be helpful for the older student with Selective Mutism. 11 Accommodations and modifications may be specified in an IEP or 504 Plan (in the US). Some accommodations are appropriate for almost any student with SM:

- Training for teacher(s) covering the nature of SM and classroom strategies; training before the start of the school year followed by on-going support

- Brief training so that all adults who might have contact with the student understand SM and how to interact with the student.

- No grading down for not speaking or for any failure to communicate that is due to the anxiety condition.

- No pressure to speak. No teasing, threatening, limiting the student’s participation, or punishment for any failure to participate that is related to the anxiety condition.

- Alternative forms of assessment and participation to substitute for speaking, such as: written work, non-verbal communication, audio- or video-taping, collaboration with friends, practice at home under parent’s supervision, the use of a computer, or the use of another person as a verbal intermediary. Individual work may be allowed for a student who is unable to participate in a group.

- Warm, flexible teachers who understand SM as an anxiety condition

- Avoid singling out the student or calling attention to any differences.

- Avoid calling attention to any new steps the student makes, such as talking in a new situation; other students should be told, without the student present, to not comment if the student with SM talks

- Do not attempt therapeutic interventions except under the guidance of an authorized treating professional or as specified in the IEP or 504 Plan, and keep written records of interventions.

- In general, except as specified in the IEP, treat the student as much as possible like any other student.

Other accommodations and strategies to consider, depending on the individual student, include:

- Clear, specific assignments and expectations; detailed grading standards or rubrics that reduce the student’s worries about what is expected

- Clear and specific prompts and questions for written work and discussion topics, rather than open-ended topics

- Place trusted friends in the same class(es). In secondary school, this probably will require hand scheduling.

- Frequent opportunities for small group activities, preferably with at least one trusted peer.

- Frequent opportunities for hands-on activities, since many students are more engaged and less distracted by worries when physically active.

- Frequent opportunities for gross-motor activity (not only organized physical activities, but also informal opportunities to get up and move around) to help the student with self-regulation.

- Teachers initiate a regular check-in with student to compensate for student’s difficulty in initiating verbal or non-verbal communication; ask if the student has any questions or anything they want to communicate.

- Seating in less conspicuous locations: back half of the room, towards the sides, and away from the teacher’s desk

- Seating next to a trusted friend and near students identified as good work partners

- Vary modes of participation for the entire class to include non-verbal communication, e.g.: students write on individual small white boards, students signal “thumbs up” or “thumbs down,” students indicate a numerical response by raising the corresponding number of fingers, students write a question or comment (possibly anonymously) to hand in

- Advance preparation for class discussions; present questions to the student the day before or earlier in the day. If the student is unable to respond, move on rather than waiting for the student to answer.

- Extended time for testing and assignments, or non-timed testing.

- Advance notice for large projects; help break projects into smaller chunks to avoid overwhelming the student.

- Alternative forms of participation in school performances. Some students with SM enjoy acting and find it easier to speak in the role of a character, and some sing or do cheerleading in a group.

- Many are too self-conscious to appear onstage even in a non-speaking role but contribute as a writer, publicity artist, set designer, or lighting technician.

- A private location to dress for PE

- Support social connections: identify potential friends and work partners; initiate activities with those students and monitor as necessary; teacher assigns partners rather than let class choose

- Encourage the student to tell others how he or she would like to be contacted, for instance if they are working together on a project that requires some contact outside of school

- Set aside an area within the classroom where a pair or small group of students can work more privately, so as to encourage more easy communication. The area might be equipped with small whiteboards, office supplies, etc.

- Social support at lunchtime, on field trips, and at other unstructured times

- Support for participation in extracurricular activities

- A steady adult, such as a trusted teacher or counselor, responsible for maintaining a continuous relationship with the student from year to year

- Disability awareness and sensitivity training for other students; monitoring for bullying; be prepared to answer questions from other students, help them understand SM, and address their

- Regular and frequent communication with the parents and outside treating professionals; communication mechanisms, such as email or voicemail, so that the parents can alert the school to immediate problems

- Support for the student’s goals in behavioral therapy under the guidance of an outside (or in-school) treating professional, including: communication with treating professional (possibly through the parents), record keeping and reporting, and carrying out the specified communication activities. Examples of activities: send student on an errand to the office with or without a buddy, student “interviews” teacher with written questions, student mouths words while class recites poem.

With appropriate support the older student with SM can achieve academically and develop social relationships. Helping students gain comfort and confidence at school fosters an environment in which they experience less anxiety and can increase the level and variety of communication at school.

1 The discussion in this and the following two sections are based on a series of lectures given by Elisa Shipon-Blum, D.O. at the conference Speaking Out for Our Children. Quality Resort Hotel, San Diego, California. 17-18 January 2004.

2 Bruce Black and Thomas W. Uhde, “Psychiatric Characteristics of Children with Selective Mutism: A Pilot Study.” J. Am. Acad. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 34:7, July 1995: 847-856.

3 Denise Chavira et al., “Selective Mutism and Social Anxiety Disorder: All in the Family?” J. Am. Acad. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 46:11, November 2007: 1464-1472.

4 E. Steven Dummit III et al., “Systematic Assessment of 50 Children with Selective Mutism.” J. Am. Acad. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:5, May 1997: 653-660.

5 “Practice Parameters for the Assessment and Treatment for Children and Adolescents With Anxiety Disorders.” J. Am. Acad. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 46:2, February 2007: 267-283.

6 Ibid.

7 R. Lindsey Bergman, John Piacentini, and James T. McCracken, “Prevalence and Description of Selective Mutism in a School-Based Sample.” J. Am. Acad. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 41:8, August 2002: 938-946.

8 Bruce Black and Thomas W. Uhde, op.cit.

9 Hanne Kristensen and Beate Oerbeck, “Is Selective Mutism Associated With Deficits in Memory Span and Visual Memory?: An Exploratory Case-Control Study.” Depression and Anxiety 23:2, 2006: 71-76.

10 Katharina Manassis et al., “The Sounds of Silence: Language, Cognition, and Anxiety in Selective Mutism.” J. Am. Acad. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 46:9, September 2007: 1187-1195.

11 School accommodations for younger students are discussed in Elisa Shipon-Blum, The Ideal Classroom Setting for the Selectively Mute Child (Jenkintown, PA, The SMART Center, 2003) and in Angela E. McHolm, Charles Cunningham, and Melanie K. Vanier, Helping Your Child with Selective Mutism (Oakland, CA, New Harbinger, 2005).

Leaflets authored by parents from their own experiences

—

What Causes SM (Carmody Factors)

Factors

The following is a list of three types of factors which are considered to be causal in the development of a child with SM:

- Predisposing;

- Precipitating;

- Perpetuating/exacerbating.

These factors are described briefly in the SMRM and were first outlined in a publication by Carmody, 1999.

In this document there is no indication of when or at which age the SM might appear except in the case where a precipitating factor might be linked to a specific event or place in time. The first day at nursery might be a classic ‘precipitating’ factor, but is not the only one. It is though easy to say that this day was where the condition first occurred, although it might be that it was just the first time that you noticed a problem.

The diagnosis of SM includes the caveat that the condition must present itself for ‘one month’. The first day at nursery is a stressful day for a child, but if after a month of stress the child has still not spoken, then there might be a case to say that this is SM.

Objective: to outline the factors listed as causal in the development of selective mutism. Very often, the family struggles to understand why their child has developed SM, and in some rare cases denial can make things worse.

Note: This document does not discuss anything related to treatment of the condition. An SM child is not born mute, they cry at birth too. They are at risk of developing SM because of genetic factors linked to their family and it is specifically the level of anxiety which will be at issue.

They might develop SM because of an event or a series of events which raise the level of anxiety in their life. The environment in which they live can cause a negative reaction raising the level of anxiety which in turn takes the form of mutism. Anxiety manifests itself is other forms too.

The onset of SM can appear at any time. Being predisposed to SM but living in a calm, happy environment will not necessarily bring on the symptoms. One or many of the precipitating factors need to appear in the environment: an event has to happen and have its effect.

A child diagnosed with traumatic mutism, which is temporary in nature, might have suffered an event which has caused the mutism, but will not necessarily be predisposed to SM. The shock of a traumatic event might give rise to mutism in a child who has never shown any signs of predisposing factors, nor has any genetic history of anxiety.

Once an SM child has shown the symptoms of SM, the mute period can be extended or made worse by other so-called perpetuating factors. What is called ‘entrenchment’ can last for years.

Predisposing

Things that an SM child is born with, genetic factors:

- Presence of a speech and language impairment in the child;

- Anxiety, wariness and hyper-sensitvity within the child;

- Family history of shyness or selectve mutism;

- Family history of other psychiatric illness, especially anxiety.

Precipitating

Factors which might occur in the environment around a child:

- Separation, loss or trauma;

- Frequent moves or migration;

- School or nursery admission;

- Self-awareness of speech impairment;

- Teasing and other negative reactions.

Perpetuating/exacerbating

Factors which make things worse or extend the period of mutism (known as entrenchment):

- Reinforcement of the mutism by increased attention and affection;

- Lack of appropriate intervention or management;

- Over-acceptance of the mutism;

- Ability to convey messages successfully non-verbally;

- Geographical or social isolation;

- Family belonging to an ethnic or linguistic minority;

- Negative models of communication within the family.

(Reproduced from the SMRM where it is adapted from Carmody, 1999)

Case Study

Predisposing: The child has a slight lisp. She displays anxiety when meeting new people or going somewhere new. This might be family members or strangers. Somewhere new might be a place set up for children to play in. She would never just go and play in a ball park alone at McDonald’s. She would only ever go with a parent. Being shy is common for many people. At the age of 14 her father was described in his school report as ‘Reticent despite knowing the answer’.

Precipitating: From very young age, the father worked away from home during the working week. At the age of 14 months she was admitted to hospital for a biopsy involving an invasive procedure and a one-week period of convalescence at the hospital. She was cared for by her mother at home until starting at nursery aged 18 months. She never spoke at nursery, and was extremely upset on her first day and every day through the period at the nursery before starting at pre-school aged 3. Aged three the family relocated to a new country. The parents separated before her 4th birthday.

Perpetuating/Exacerbating: The mother and maternal-grandmother show extreme forms of affection whilst expecting her to reciprocate their approach. There is constant reference to her as ‘angel’ (and many other terms of endearment). At the same time intervention by the mother in her mutism at an early age included regular threats of corporal punishment for failure to speak, to eat or to behave in the prescribed way. Being effectively tri-lingual she lives in a world of multiple languages, with all members of the family varying the language spoken around her. She is often spoken about in her presence.

Taking the case study, it isn’t difficult to compare the list factors and see that over half of those factors are present in the case. This child was silent from nursery until the age of 8. Reading the list of factors published in the SMRM for the first time, and reading between the lines, was in short, enlightening. This list of factors describes so many although not all cases display all of the factors of course, so don’t try too hard. Being honest is sometimes brutal, but it might just help you understand. Ignorance is not bliss, but it has got you here reading this document as a parent, thinking: ‘Did I?’ hasn’t it?

How the factors present themselves

This section looks at the factors again, and hopefully tries to go a little deeper into the list by describing them in a different more pragmatic or real way. Each reader might see the same list with a different case history in mind. Your child might have first displayed the symptoms in the early years, or maybe not. Maybe the symptoms appeared later as a result of an event … The predisposition hadn’t manifested itself, the genetic lineage was dormant, until that day when … you know what I mean.

Predisposing

- Presence of a speech and language impairment in the child; A child might have some speech impediment but if they themselves are unaware of it why should it be a problem. Awareness of being different comes with repeated mention of the difference. Negative connotations can be easily associated. Saying ‘You sound funny’ or ‘Don’t speak like that’ will reinforce the negativity and can themselves appear very close to bullying.

- Anxiety, wariness and hyper-sensitivity within the child; Some children are anxious by nature. This can be genetic.

- Family history of shyness or selective mutism; The fact that anxiety can be genetic might result in anxiety for a child.

- Family history of other psychiatric illness, especially anxiety. Similarly, some family members share other illnesses and disabilities.

Precipitating

Separation, loss or trauma;

Separation from a family member can be the cause of anxiety. This might be simply the absence of a working parent (business travel, government service abroad etc.). Many absent parents have no choice in the matter. The loss of a parent (divorce, death) can obviously be very difficult to handle for any other family member. Trauma can occur to anyone at any time. This could take the form of medical trauma, an accident, a natural disaster, war etc. There is at this point a need to mention the existence of traumatic mutism which tends to be temporary in nature, but can lead to entrenched selective mutism if not properly treated.

Frequent moves or migration;

Moving house can be a busy time for a family. Stress levels will go up. An anxious child will handle stress differently. Anxiety can be caused simply by changing the layout of a room, moving house, resulting loss of friends, a new environment. Changing countries adds another level of potential anxiety. A new country can give a culture shock beyond any other. New places, new sounds, new weather, new voices, anything new can bring out anxiety.

School or nursery admission;

Nursery is a new place, a new room with new people around you, new colours, new noises, a new routine, new hands, new smiles. You are removed from those who have been close to you, maybe for the first time.

Self-awareness of speech impairment;

Being self-aware can drive anxiety. ‘I’m different?’ This leads to more questions, no

answers when you are young because you just can’t formulate a question. Conforming to expectations might come later, but already ‘I sound different inside my head’ can be worrying.

Teasing and other negative reactions;

Teasing within the family or the extended family can be very destructive. A simple reaction to a ‘wrong’ sound or a failure to make any noise at all will potentially reduce the willingness to try. Teasing is one step removed from bullying. It might be innocent at one level while bullying is deliberate and divisive. Bullying should be seen as negative. Bullying at any age can lead to the onset of SM in an already anxious case.

Perpetuating/exacerbating

Reinforcement of the mutism by increased attention and affection;

Too much TLC, like too much chocolate isn’t always a good thing. Reacting to a disability by an overdose of honest love can unfortunately have negative outcomes. Smothering love has the effect to blocking release. Wrapping a child in ‘cotton wool’ prevents the risk of damage, where actually taking the risk might be beneficial.

Failing is a learning experience. Falling over hurts, but you learn not to do it again in the same way. A simple hug isn’t always appreciated, it can be invasive: someone’s in my personal space. We all have a personal, physical space. You, me, and the child you love so much … and the adult with SM is potentially even more anxious about your excess of affection. It’s case by case, we’re all different, don’t assume anything.

Lack of appropriate interventon or management;

Doing nothing is a choice. Doing something is a choice as well. Whether interventon

is possible is another story. The wrong interventon may be worse than doing

nothing.

Over-acceptance of the mutism;

‘That’s OK, they’ll grow out of it’. Well that’s a classic phrase, but the reality is not exactly that. Some children don’t just grow out of it, very few in fact. Speaking for a child is an option, but it doesn’t necessarily help them, whether you are a parent, family member or a child in the same class at school.

Ability to convey messages successfully non-verbally;

Signs can replace speech. Nodding, pointing, shrugging, and the acceptance of such non-verbal motons in replacement of speech is acceptable of course, but not in the long term. Some SM children are not able to communicate even non-verbally.

Geographical or social isolation;

Being away from regular interaction for whatever reason will deprive someone of the opportunity to converse or even to learn to converse.

Family belonging to an ethnic or linguistic minority;

Changing countries leads to you being seen as different within the host community. Some hosts accept difference more easily than others and bullying again rears its ugly head. When it comes to speech, a new language is a challenge. Having an accent is an excuse for teasing and eventually bullying. Being a Geordie in a class full of Scousers is bad enough, but being an SM child anywhere … The time it takes to acquire a language is a time of risk, risk of not understanding simple instructions and the risk of being misunderstood.

Bilingualism should be included in this sub-section. Children born into a family where there are multple languages are also at risk. A so-called “language delay” might occur as a child takes an extended time to acquire the basic vocabulary. A parent mixing languages when talking to a child will only confuse, cause delay or worse.

Negative models of communication within the family;

Bad language, aggressive language, negativity can all add to anxiety. The comments in this document come from a parent. They are all drawn from personal experience and based solely on an interpretation of those basic factors.

The objective of this document is twofold:

- To compare the list against experience (e.g. the case study)

- To try to impart that experience to a wider audience through the theory, and hopefully making the theory more accessible to others.

Sometimes the professionals hide the reality in a phrase, and reading between the lines is not always easy. The word ‘trauma’ can mean many things to many people. Affection can be a positive and sometimes in excess it can be completely destructive. In the good old days a ‘clip round the ear’ was all it would take, wasn’t it. Events happen. Ignorance is one of the biggest factors in the entrenchment of SM. It’s never a crime to be ignorant. It’s not a crime to hope either but between ignorance and hope, there’s a lot we can do to raise awareness, react in an informed way, change the environment around a case of SM, and have patience, buckets of patience.

Written by Dad.

PS Read between the lines!

SM Spaces

This document is published by SMIRA and is written by a dedicated parent, known to SMIRA, from their own experiences, in the hope that it will be useful to others.Disclaimer: The opinions expressed here are not necessarily the views of SMIRA.

One word: ‘Spaces’

We all have them. Call them ‘comfort zones’, ‘safe places’, ‘body space’ whatever you like. One person chose to call them ‘spaces’ in order to try and explain a concept to other people. The concept is about human nature. It’s about self-defence. It’s about nurture and support. It should not be about anxiety or invasion.

Explaining something which is difficult is sometimes a difficult task. As a basketball coach this dad used a basketball metaphor to achieve his goal. Your body space is sacred on a basketball court. In theory any contact is a foul, and 5 fouls in one game and you’re not allowed to play anymore.

In this document this dad tries to convey the message about spaces in relation to Selective Mutism (SM). Anyone with SM, even the youngest person has their own space. But with SM your space is threatened. Your anxiety levels are excessive many things can lead to increased anxiety, which in turn, and for those with SM, leads to a failure to communicate.

In order to overcome this, the spaces concept tries to help build and manage new, safe, comfortable spaces for those needing them. Over time, and the more spaces that exist, the concept says, that person with SM should be less anxious, and therefore more able to communicate. Speech generalisation comes when many spaces are ‘talking spaces’.

Read the document, and then think. Have you got spaces? Can you build a space for someone else or are you a space invader?

SM Spaces

This is what I understood about what my daughter (MissT) needed once we had the diagnosis for SM aged 5 and a half. The Ed.Psych said SM was like a pressure cooker with the lid on. With a pressure cooker you want to control the steam to cook the food, and release it once the food is cooked. This obviously doesn’t work with SM, because you need to let out the pressure to speak … The other problem is that if you just let the steam out, it dissipates, it is not useful anymore and it disappears.

What I understood that day was that yes, we could take off the pressure to speak, but we also had to put in place something where MissT could relax outside of her ‘pressure cooker’. Let her out if you want, but give her a ‘space’ where she was free of pressure. At the same time I had the *SMRM1 book and decided to follow instructions (so to speak). For me that meant two things:

1. Release the pressure

2. Create her space

Her space would be somewhere where she was relaxed, but somewhere where she could learn to speak. The space needs structure, needs planning, needs looking after, and needs to grow with her.

The SMRM book says ‘treat the SM where it occurs’ … so her space was for me, always going to be at school, but school obviously had to agree.

We had the planning meeting, I explained my idea, and school agreed. The primary teacher would take off any pressure to speak to him, and the SENCo would do the sliding-in. MissT was unaware of the plan … she was happy to slide, and off she went.

As parents, I also discussed with my ex- that ‘we’ had to take off the pressure at home. We should never discuss ‘talking’, never ask ‘how was your day’ etc etc … wait for her … it’s a risk, because she might never tell us anything …

The plan worked. She’s now talking … She’s now a ‘shy’ 11 year old.

What I do now is that I continue to manage her space. She has a space with her mum ‘at home’, and she has a space at my house with her little brother and sister me and my partner. She has ‘school’ as a space, she does sleepovers, she travels by bus, swims, rides her bike, all spaces which I slid her into … graded exposure … no pressure to dive in, no pressure to get that bus …

One space leads to another. Spaces merge:

– School merges with home : homework

– School merges with friends : Sleepovers and so on

The idea I guess is that everything merges to become ‘MissT’ at the end … she will live her life in her space! I’m very careful even now to talk to her like this. She does NOT have to grow up because I say so! She will grow up, fall over, learn and advance through life, not with me telling her how to make every move, but on her own because she has learned to live in her space. If needed I’ll slide her into another space … whatever that may be: job, work experience, college, relationships …

The opposite is also true, as with anything in life. If someone is in your space, they might be welcome or they might not be. The bad guys can be called space invaders. We all know them, they wake you up when you’re asleep, they ask you to do things you can’t do, they put pressure on you do things you can’t do and worst of all they invade your space.

Changes can happen to spaces, they can happen to you. You can move into a new space, a school, a new house, you can migrate to a new country. Are those new spaces good for you? Are those old spaces full of bad memories? Would you go back to a bad space? The concept can be turned forever. The idea is to exist in anxiety-free spaces.

The plan is to make them. Can you build a space on your own? A Do-it-yourself space? Do you need someone to help you? Do the people around you understand spaces? Is the person you know that has SM in a happy space? Are they communicating in that space? Can you help them make a space bigger? Can you help them make a new space?

Space, they say, is limitless, so are ‘SM spaces’. Go create one …

Appendix

References

Glossary

SM – Selective Mutism

SENCo – Special Educational Needs Coordinator (in-School role)

SMRM – Selective Mutism Resource Manual

Bibliography

*SMRM – Selective Mutism Resource Manual (Johnson & Wintgens, Speechmark 2001)

Published by SMIRA

Outgrowing SM – the Myth and the Effect of Change

1. Introduction

In the book Tackling Selective Mutism (Sluckin, Smith, 2014) from the chapter on Care Pathways, written by Maggie Johnson, Miriam Jemmet and Charlotte Firth, there is a section which states:

Page 183: First section.

“Services (UK) are aware that by dispelling the myth that it is safe to wait for young children to ‘outgrow’ SM, the need for more costly or extended intervention at a later date will be reduced.”

Opinion

To me, this is a very clear statement that young children should not be left without specific support, they will not just ‘outgrow’ SM. Those responsible for their care should not leave an SM child without the support, care and therapy that they need. To me, it is a myth.

The myth should/must be dispelled in order to prevent the long term effect of SM which will be more costly to treat than it would be if it has been treated effectively in early years.

The cost is not purely the cost of later treatment, for potential depression for example. This cost can be measured by the health service in question in financial terms, but it should also be measured in the human cost: the effect on a human being of being left without the correct diagnosis and treatment. The human cost is unmeasurable in financial terms. Our children are priceless.

Preventative medicine is lower cost than delayed or reactive medicine. Proactivity has a cost but it is usually cheaper than reactivity and the degeneration of someone’s health. We are talking about mental health, in the main. The problem, in the future for some can degenerate from mental health to their physical well-being. Depression can lead to selfharm, overdose or worse.

SM is identified internationally by the APA DSM5, the UN-WHO ICD-10 and therefore the diagnostic criteria are visible around the World.

What follows is my own take on the debate, which I base on the above quotation. One thing leads to another. This document also discusses the effect of change on SM and suggests a few things to think about.

2. Outgrowing SM

I begin this section with a series of questions to promote the debate:

- What does it mean to outgrow SM?

- Does a child get older, and suddenly at a certain age the SM disappears?

- Is the anxiety that drives SM age dependent, so that it disappears at a certain date, or when the child reaches a certain physical state, weight, height or puberty?

- Can a child make a conscious decision to break out of the SM cycle?

I don’t believe that children just outgrow SM. It doesn’t just disappear independently.

Personally, I’m very tall. I was a ‘refuser’ at pre-school age. I took entry to primary school very badly but my mum will tell you that the only thing I ever grew out of was my trousers and my hand-knitted pullovers. I was lucky to have some good teachers to help me overcome my school anxiety. One of those teachers remains a close family friend to this day. She will tell anybody that my sister was in her class and famous for blooding the nose of one of her 5 year old classmates, while I was in the room next door unhappy with the separation from my mum after 4 years of 24/7 care and affection.

A myth is a myth. It’s a story which is untrue. Mythical monsters with eight arms? It’s just fiction.

Anecdote 1

I recently discussed outgrowing SM with someone who said they out grew SM.

“I did, A change of schools following a house move aged around 7 did it for me”.

Was it because they reached the age of seven that the SM disappeared, or was it the house move, or maybe the new school?

Personally, I’d say that the SM was associated with school space before the age of seven, and the opportunity to go to a new school removed the associations this person had with anxiety in the old school. The cause of this young child’s anxiety was removed by change.

The new school didn’t have the same feeling as the old one, the old school being where the SM began. SM is selective by definition, that first school was the place where the SM occurred. The second school was a new environment, a new space without those old associations and without the mutism. Similarly, moving house can have both a positive and/or negative impact.

At this point I usually say that this child moved from one space to another, from an anxious space to a non-anxious space. This is nothing to do with outgrowing SM, this is everything to do with the selective nature of SM and the word ‘change’ which I’ll come to in a later paragraph.

Anecdote 2

A teenage boy overcomes his SM by himself. Somebody told me this story. It would seem that peer pressure played a part in motivating the teenager to overcome his mutism. He was no longer willing to miss out on what his peer group were getting up to. The pressure to join-in overcame the anxiety associated with speaking. The influence of an external factor may be significant in this case.

Again, a change occurred and affected this teenager. His friends changed. They moved their focus onto other things. He was left alone. He had the chance to follow them and succeeded. Did he outgrow SM or did his environment change?

Anecdote 3

I talk a lot about my own daughter MissT (12, ex-SM). Using her as an example as I try to explain something.

I changed a number of things in her life. These are visible in the next section of this document. I dictated those changes on her life, and I regret none of them. Maybe one day she’ll tell me I made a mistake which is fair enough. On the whole I’d say I’m happy with the end result, although at nearly 13, there’s more to come in terms of change.

Recently the admins in the SMIRA FB group were debating the idea that someone could outgrow SM. On behalf of the team, I’m happy to say that we prefer the term ‘overcome’ ahead of terms like ‘cure’ or ‘outgrow’.

3. The effect of risk and change on SM

Personally, and professionally I spend a lot of my time thinking about the subject of change. As a student of history at University change is visible across the ages. Single individuals are able to effect changes which impact entire nations, continents, peoples, religions. Change is part of our history. Nothing is ever the same forever. Things change.

Some changes are out of our control, others can be managed. SM is driven by anxiety. Anxiety occurs at different levels at different times, and in different places. SM is selective in the sense of the situation, not a choice, but driven by anxiety.

Carmody* identified 3 groups of factors which can influence someone with SM. I call them the 3P’s and have discussed them in other documents.

Each factor on the Carmody list is a risk. The risk that it might cause increased anxiety. Each risk has an effect if it occurs. Not all risks occur. Some never occur, others can be avoided, reduced, transferred. We can all mitigate risks once they are identified. We can identify responses to a risk based on a ‘what-if’ scenario. If a risk occurs, then we have to deal with the effect.

If we are proactive about risks, we can make a change. Changes can be made. Change is risk mitigation. If we are reactive about risk, we will be too late.

One of the biggest questions about change related to SM has to be whether the child is informed of the change, if it is proposed by a parent or professional. Would you discuss moving house with a young child, or just make the decision with the best intentions and get on with it. Does a young child’s opinion matter? What about a teenager? Can an SM adult make a ‘change’ decision or does the anxiety preclude this? What if you have to change, you don’t have the choice and you are forced to change something?

Unexpected changes happen too. Some changes our unpredictable, out of our control. They happen. They might be traumatic in one extreme or might be the slightest changes at the other end of the change spectrum.

– A teacher who is absent or off sick for a day is a temporary change and raises anxiety but it is by nature ‘unexpected’ on that day. It’s part of life.

If you have to change, you can look at a change forever, but eventually a decision has to be made.

What is a change?

A change alters something.

You might change clothes, food, house, school, car, partner, job, the list is endless. Everything can be changed.

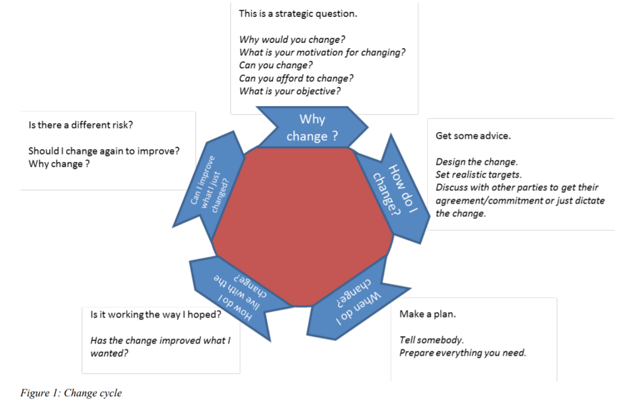

Change can be described in a cyclical way, as per the following figure which starts with the question Why?

Figure 1: Change cycle

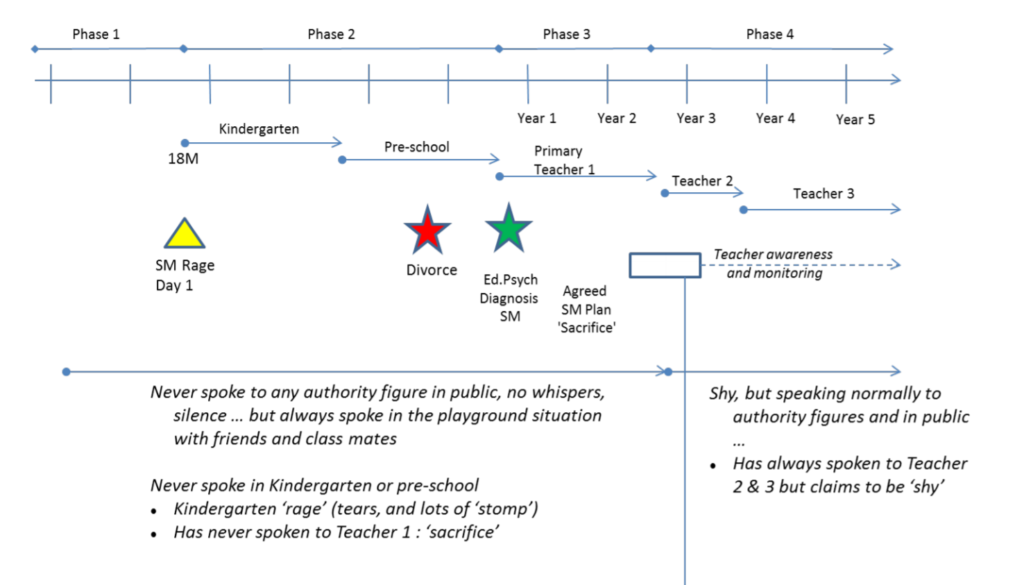

4. Timelines

I use timelines a lot at work. They help to describe events over a period of time in a visual way and allow a multi-agency group to get around the table and see things together. This is one way of looking at the effect of changes.

Individually we could all describe our own timelines. A sequence of events over time including birth, starting school , getting a job, reaching a landmark birthday, retiring etc. Each timeline, sometimes unfortunately, comes to an end.

The basic elements of a timeline are

– A line with the time period marked on it

– Events or milestones can be marked on that line

– Phases or stages along the timeline. This might include future plans or past periods of time.

The following timeline as a real SM timeline for a certain person I know very well. I have simplified it and removed a lot of details from the original in order to make it more generic.

The features of this SM Timeline are the points at which change occurred over the timeline. The milestones are clear. The changes were dictated. There was no concept of giving the child a choice in any of this before the age of 8.

Milestones

– SM day 1 (onset of SM, first anxiety attack)

– Divorce

– Diagnosis of SM by a professional Ed. Psych.

– Plan start date

– Generalisation start date (vertical line)

Changes

– First day at nursery

– First day at kindergarten

– Divorce (yes it was a significant change in the timeline)

– First day at primary

– Teacher transition 1

– Teacher transition 2

SM Timeline

5. Planning Change

In this timeline there are a number of plans which were set and implemented. These were not all beneficial:

– Plan to start kindergarten (Dump and Run strategy)

– Plan to start pre-school (No introduction session)

– Plan to start primary (No introduction session)

– Plan to start SM therapy (No communication to the child)

Aged 6, I decided to NOT communicate the plan for SM therapy, in conjunction with school staff. It worked. Their own internal processes were already in place, and adding knowledge from the SMRM helped that programme.

Recommendations for planning these kinds of changes include items such as

– TAC Team Around the Child

– Gradual exposure of the child to the new situation (Stimulous fading, or formal sliding-in)

– Awareness knowledge transfer to those in the TAC

– Age appropriate discussions with the child about the planning etc.

A plan should have

– Reason (Why)

– A defined end result (What)

– An organisation (Who)

– Defined target benefits (How much)

– Defined stages or steps along the way (How)

– Regular communications to the organisation

– Flexibility in the event of unexpected events. (All plans change)

I did not put the ‘When’ in this last list.

If the change is unexpected, you still have to do the ‘How do I live with the change?’. In all cases I adopt and adapt any good ideas. Whatever the idea is. Adapt the idea to the situation you are in.

Where would MissT be today if I hadn’t dictated some changes on her life? If I hadn’t been given the SMRM? If I hadn’t have had the support from school? Would she have grown out of SM? She’s tall like me. She grows out of her clothes too. She overcame her SM with a little help … Like it says at the bottom of the page, I’m just a dad 😉

—

*Carmody L. The Power of Silence: Selective Mutism in Ireland – a speech and language perspective. Journal of Clinical Speech and Language Studies, 2000;1,41-60

—

I’m just a dad

Multi-Lingualism and SM

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

Summary

This document was co-authored by a parent and Maggie Johnson (UK, NHS) and includes numerous references to research materials related to the specific topic covered by the document.

The parent is just a dad, father of three multi-linguals, the eldest of which was diagnosed with SM aged 5. Following intervention based on literature originally authored by Maggie Johnson and Alison Wintgens (Selective Mutism Resource Manual, 2001) his daughter was speaking in school 18 months later.

Since then, Dad continues to monitor her progress, and this document is one result of her experience.

This document is published by SMIRA and is written by a dedicated parent, known to SMIRA, from their own experiences, in the hope that it will be useful to others.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed here are not necessarily the views of SMIRA.

Multi-lingualism and SM

This is a favourite subject of mine, simply because my daughter MissT is tri-lingual, and used to have SM. She migrated from one European country to a neighbouring European country aged 3. Both countries are at least bi-lingual. For this reason, I will discuss migration as an issue in this document, as migration sometimes incurs a new language.

In the Carmody Factors* list, two factors are mentioned in the list of 3Ps

P2: Precipitating

• Frequent moves or migration

P3: Perpetuating

• Family belonging to an ethnic or linguistic minority

The Silent Period

For anybody learning a second or even third language, it takes time, time to acquire the vocabulary (words) and time to hear the accent. The research has shown that many children have a so-called ‘silent period’, while they try to acquire a new language. This is a very different concept to what we know as SM.

http://www.ascd.org/publications/books/106048/chapters/Key_Concepts_of_Second-Language_Acquisition.aspx

The younger the child, the longer the silent period tends to last. Older children may remain in the silent period for a few weeks or a few months, whereas pre-schoolers may be relatively silent for a year or more. However, a silent period of several months is by no means inevitable nor even typical in second language learning.

There is probably no set timescale for learning a language. Everybody learns at different speeds. Some young children will be fluent in class with their peers in 6 months. It would be dangerous to let 6 months of silence go by and then expect children to suddenly start speaking. But as parents of children with SM will know, bombarding a child with questions as recommended by Priscilla Clarke (1992) is not the answer either! See:

www.naldic.org.uk/Resources/NALDIC/Initial%20Teacher%20Education/Documents/Stagesof earlybilinguallearning.pdf

Identifying SM

The diagnostic criteria for SM are globally the same. Defined by the United Nations UNWHO F.94 or DSM5 (previously DSM-IV-TR). Nursery staff, teachers is pre-school or primary, or Secondary depending on the age of a child will see an anxious child undergoing a culture shock as they try to assimilate culture and language in a new environment. Yes, a new space!

Diagnosis

Recently Maggie Johnson has told me that she advises of “potential SM during the silent period in a second language learner’s new school environment”. This does not mean a longer period (e.g. 6 months) before diagnosing a child with SM, where the child is living in a world using their second language. This silent period is “a time of language learning and inner language rehearsal when, for whatever reason, the child is not ready to speak outwardly, but is processing the language inwardly. Their understanding may be no more delayed than their speaking counterparts.” As we know with SM, the simple ‘failure to speak’ will hit a child very hard if they are trying to learn a second language. Maggie’s advice goes on to say “If a bi/multi-lingual child was showing signs of anxiety in the ‘silent period’, with other signs of selectivity (e.g. limited non-verbal communication in school setting) and was capable of using the new language in some settings (e.g. playing with new school friends at their home) I’d definitely be making a diagnosis of SM before the child emerged from the silent period, rather than waiting six months.”

Research Statistics

Maggie Johnson has also given me access to research from Israel which shows statistics giving a higher than normal rate of SM for immigrant children 2.2% instead of 0.76%. (See below Elizur & Perednik, 2003). Anxiety tends to rise when you migrate as is noted in the Carmody list.

Environmental factors

SM is a global phenomenon. It is identified by the World Health Organisation (WHO) which deals with most of the world’s population via the United Nations. The majority of cases of SM will not be bi-lingual.

Some countries are legally bi-, tri-, or even quadri-lingual. Think about Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, India, China, Singapore etc. These countries do however have education systems which recognise other languages in a much better way than a mono-lingual country. At the same time, migration is and has always been a global issue. Peoples have always moved around. It’s a natural process. The idea to cross international frontiers is artificial, but it is a fact of life which sometimes causes harm. I can think of so many cases where international borders are causes of dispute, which in turn ‘force’ families to migrate. It’s nothing new.

Cultural boundaries exist as well. A foreigner will always be different, until that is another group migrates into the foreigner’s area, and they themselves become the locals. Think ‘Irish in New York’ …

Differences always cause friction. Friction can appear as violence, bullying, or even teasing in the negative sense. Some cultures accept difference positively, others don’t.

Support Approach for SM

Treatment, therapy and awareness all have a role to play.

SMIRA always advises ‘sliding-in’ for treating SM, either an informal approach or a formal sliding in programme with small steps targets.

A new child in class? Make them at ease by helping children settle into new environment without feeling pressured to speak before they’re ready giving time to slowly acclimatise to their new environment. Informal sliding-in using parents and peers is absolutely fine however (no specific target sheets, just respecting child’s space and only gradually getting closer as they talk to and play with parents/peers). Sometimes it will take longer than you planned. With SM, even longer, and by putting pressure on them, even longer still.

Personally, I think this ‘informal’ sliding can be used almost anywhere where there is anxiety. I’ve been sliding MissT in and out of places for years, and I personally slide in and out of her space whenever I see the need. I’m managing her space from the outside.