Below is a range of leaflets suitable for use by Health and Education professionals. Please also see the other sections for more general information.

The documents below are in three sections:

- view the documents in the preview panes, or

- click Open to view the document at larger size in a new page, or

- click to Download the document (as a pdf to your computer) for printing or sharing via email.

SMIRA Leaflets

—

Where to Get Help with Selective Mutism

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

The information charts below are particularly relevant for England and Wales (UK) but contain general points which may be useful elsewhere.

NB: Page 4 below contains a glossary of abbreviations

The links shown on the flowcharts are given in clickable form underneath each flowchart

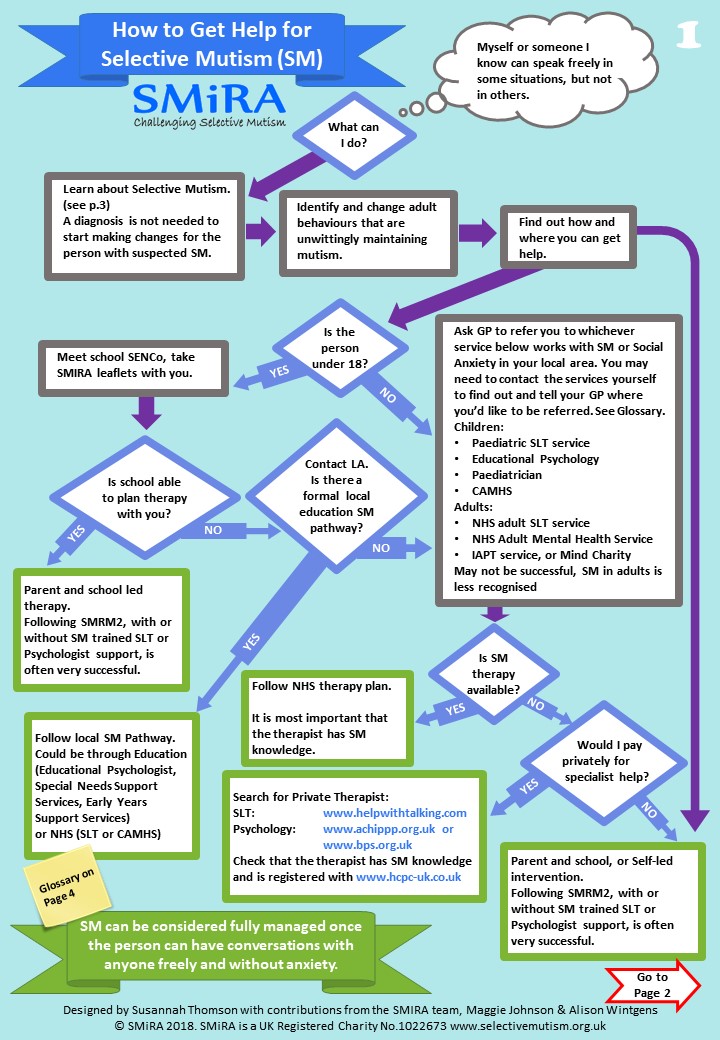

1. How to get help for Selective Mutism

Links given on page 1 above:

Search for Private Therapist

- Speech & Language Therapy: www.helpwithtalking.com – go to ‘advanced search’, tick the SM button and extend the distance it reports on as support can be done remotely for you

- Psychology: www.achippp.org.uk or www.bps.org.uk

Check that the therapist has SM knowledge and is registered with www.hcpc-uk.co.uk

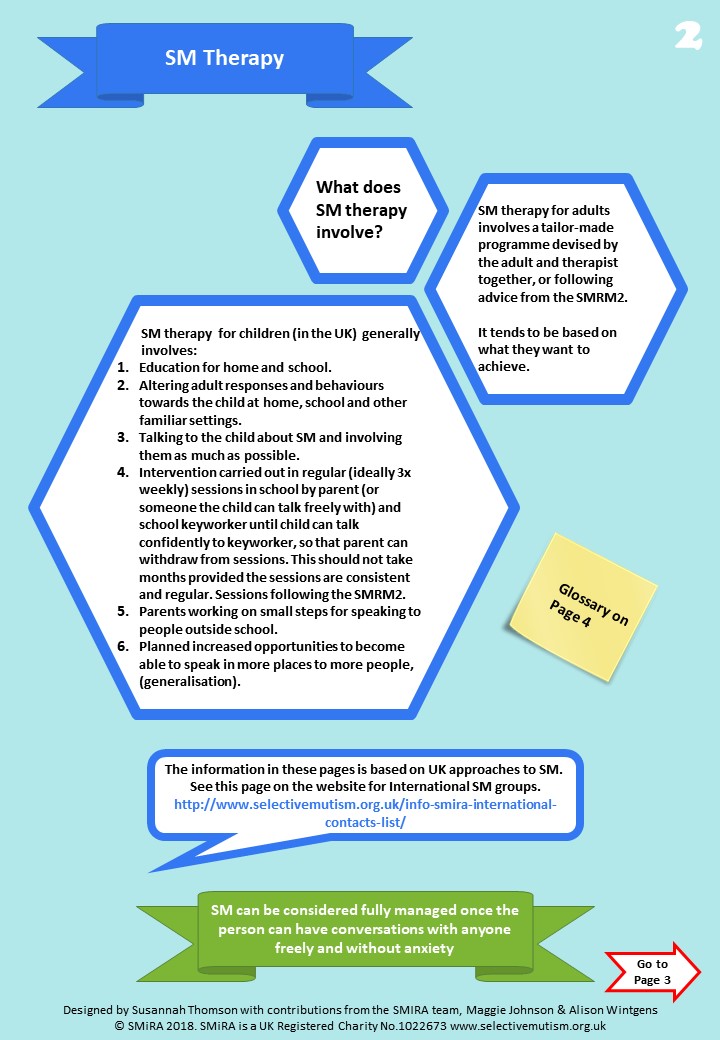

2. Selective Mutism Therapy

Links given on page 2 above:

SMIRA International Contacts List

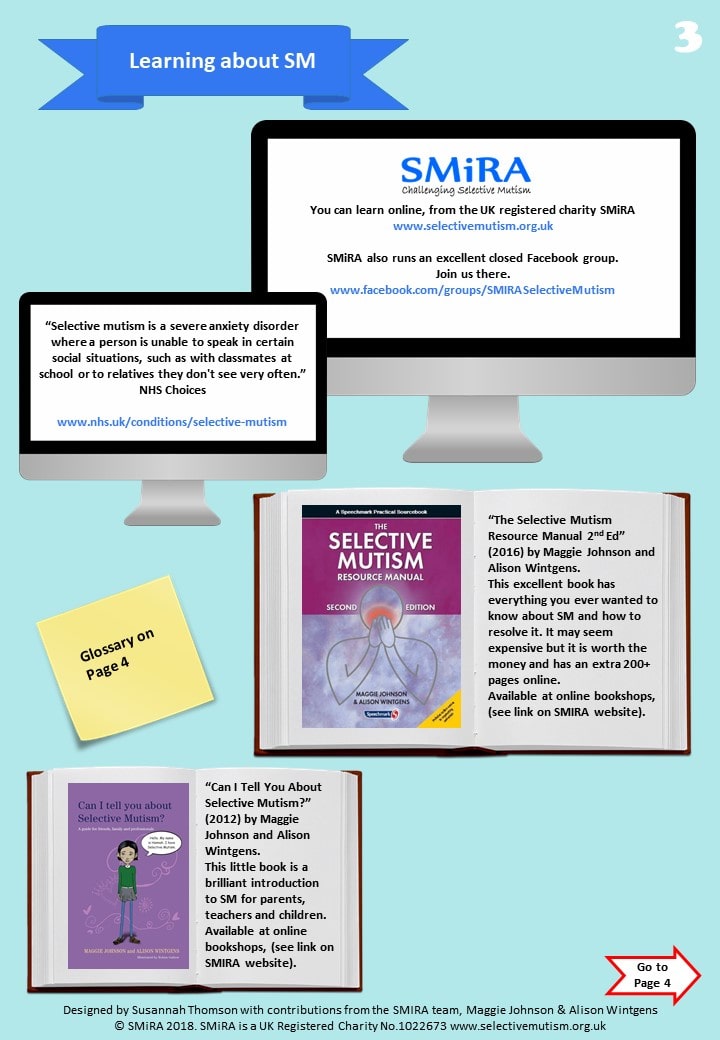

3. Learning About Selective Mutism

Links given on page 3 above:

- Learn online, from the Information section on this website

- Join the SMIRA Facebook Group (it’s a closed group so there may be a short wait while we approve your membership request.)

- See NHS Choices – Selective Mutism

Additional Reading

Details and purchase links for all of the books below are on the Books page on this website.

- “Selective Mutism Resource Manual 2nd Edition” (Johnson & Wintgens). Most changes in 2nd Edition are for older people with SM and generalising outside school

- “Tackling Selective Mutism” (Sluckin & Smith, ISBN-13: 978-1849053938, ISBN-10: 1849053936)

- “Can I tell you about Selective Mutism?” (Johnson & Wintgens, ISBN-13: 978-1849052894, ISBN10: 1849052891)

- “Can’t Talk? Want to Talk!” (Jo Levett, ISBN-10: 1909301310,ISBN-13: 978-1909301313)

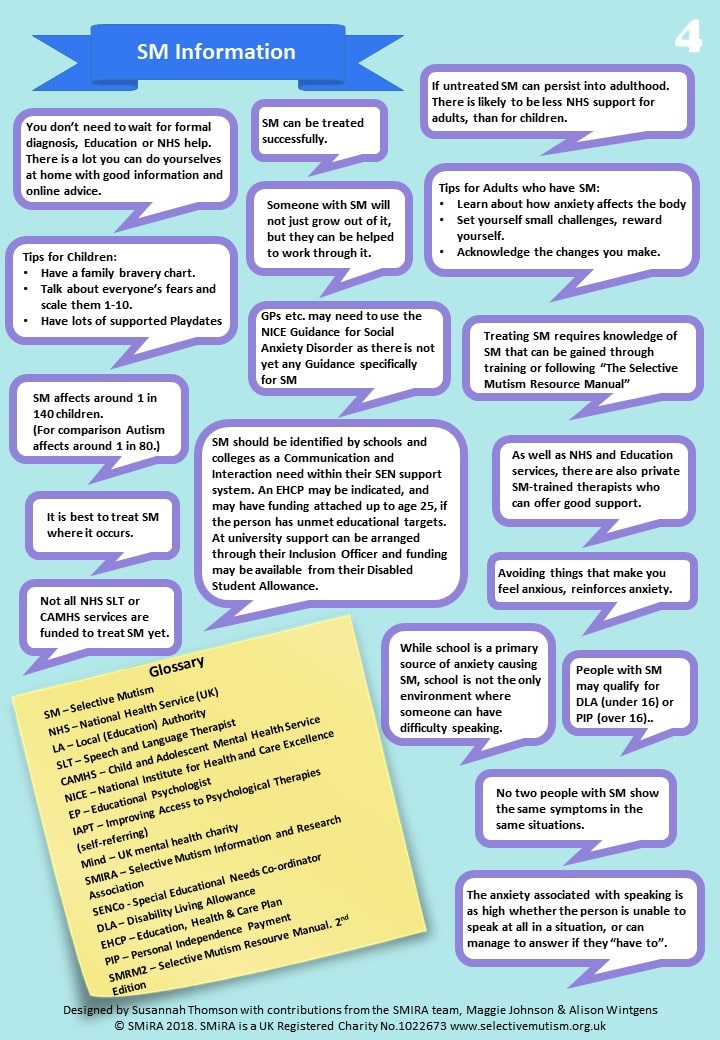

4. Selective Mutism Information

You may download these flowcharts to your computer as a PDF file, for emailing or printing out:

Suggestions for Intervention

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

Suggestions for Intervention for Selective Mutism in Children

The Selective Mutism Information and Research Association (SMIRA) has put forward the following suggestions for health professionals and families:

-

- Assessment: because some SM children suffer from other communication disorders that can easily be missed, a Speech and Language Therapist’s assessment should be requested. This can be managed by a home visit or use of recordings if necessary. A psychologist’s assessment is also advisable, but intervention should begin at once.

An experience all too commonly reported, is that children are moved around from one waiting list to another, without actually receiving the help they need.

- Early diagnosis and treatment is important. It is unhelpful to ‘wait and see’ as this could lead to entrenchment and possibly longer term problems. The ability to speak in some situations, but not in others, indicates Selective Mutism.

- Parents and carers must be provided with support and up to date information such as that provided by the SMIRA helpline or its handouts and website.

- All pressure to speak must be removed by all those with contact with the child.

- Offering help at a very young age through an informal play approach has the best chance of success. This usually takes the form of facilitated noisy play during which confidence is instilled and trust is built; adults make mistakes which children become eager to ‘correct’ and uninhibited laughter is generally encouraged. Interaction with animals can also help.

- Older children have been shown to respond well to a very gradual ‘step by step‘ desensitisation approach based in the behaviourist tradition. (Trained professionals from several disciplines, as well as teaching assistants have been able to deliver this.)

- A small minority of SM children will need specialized services such as CAMHS, as their problems are complex and their environment may be problematic. This is sometimes combined with formal CBT. It should be noted however, that unusually minute and gradual steps in the behavioural aspect of treatment are required if the actual speech behaviour is to be changed. Broad, general recommendations are not effective.

- The possible role of medication requires careful thought and is currently used more in the US than in the UK. It is discussed by a Child Psychiatrist in Smith and Sluckin 2015 pp 131-137.

Information and Support

Selective Mutism Information and Research Association (SMIRA) Reg Charity No.1022673.is a national UK support group based in Leicester. It also has overseas links.

It deals mostly with children and parents and has a ‘facebook’ membership of over 3000. It is in touch with many of the leading specialists in the field of Selective Mutism (SM).

www.selectivemutism.org.uk

Email: info@selectivemutism.co.uk

Phone: 0800 2289765

Facebook: Smira – Selective Mutism

There is a completely separate support group for SM adults:

www.ispeak.org.uk or email carl@ispeak.org.uk

Books

Tackling Selective Mutism: A Guide for Professionals and Parents

Benita Rae Smith and Alice Sluckin Eds. 2015

Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London and Philadelphia

ISBN 978 1 84905 393 8 paperback, 308p, £19.99 (royalties to charity)

The Selective Mutism Resource Manual (2nd Edition) Johnson, Maggie and Wintgens, Alison (2016) Speechmark, Bicester, Oxfordshire:

Can I tell you about Selective Mutism? A guide for friends, family and professionals

Johnson, Maggie and Wintgens, Alison (2012) Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London.

Selective Mutism. An assessment and Intervention Guide for Therapists, Educators and Parents

Kotrba, Aimee (2015)

PESI Publishing and Media. Eau Claire, Wisconsin:

Helping your Child with Selective Mutism

McHolm, Angela E., Cunningham, Charles E. and Vanier, Melanie K. (2005) New Harbinger Publications, Inc., Oakland, CA

The Selective Mutism Treatment Guide: For Parents, Teachers and Therapists. Still Waters Run Deep

Perednick, Ruth (2011) Jerusalem. Oaklands

Helping Your Anxious Child

Ronald M. Rapee. 2nd Edition 2009

New Harbinger Press

Also Recommended:

Silent Children – approaches to Selective Mutism – Book & DVD

Edited by Rosemary Sage & Alice Sluckin (2004),

University of Leicester

(Available to purchase from SMIRA)

Guidance for Diagnosis of SM

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

Guidance for the Diagnosis of SM

One question that comes up frequently, with relation to Selective Mutism, is how can we diagnose SM in a case where the patient also has a diagnosis for another disorder such as ASD? At SMIRA we have seen many cases of comorbid (or co-existing) SM with other disorders particularly those on the Autism Spectrum (ASD). Many of the diagnoses of SM precede ASD assessments, although some SM assessments do come after an ASD assessment. The problem we see is that in some cases the SM assessment is not performed because it is assumed that the ASD assessment is enough to explain all of the behaviours apparent in the patient.

SMIRA’s position on diagnosis of SM:

a. Diagnosing practitioners should make an assessment for SM where they believe the patient meets the criteria for such a diagnosis.

The preferred diagnostic criteria prior to the publication of ICD-11 in 2018 were those published in APA DSM5, which lists SM as an anxiety disorder. ICD-11 classifies SM as an ‘Anxiety or Fear Related Disorder’. It lists as exclusions:

- Schizophrenia

- Transient mutism as part of separation anxiety in young children

- Autism spectrum disorder

Exclusions in the context of ICD-11 are ‘terms which are classified elsewhere’ and which ‘serve as a cross reference in ICD and help to delimitate the boundaries of a category’. This means that SM and ASD are classified as separate disorders and can therefore be diagnosed as co-morbid. This differs from the definition of exclusions used in DSM5 as ‘does not occur exclusively’.

b. Diagnosing practitioners should make a separate diagnosis for SM even if there is a pre-existing diagnosis for another disorder. SMIRA believes that ‘excluding’ SM as a comorbid diagnosis in DSM5 has been very unhelpful to medical practitioners and their patients. This is especially true in the case of ASD. We believe a person with ASD can also be selectively/situationally mute (SM), and this is allowable using ICD-11 classification.

This position is made clear in The Selective Mutism Resource Manual 2nd Edition and in Tackling Selective Mutism, the latter being endorsed by Professor Sir Michael Rutter (Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London).

Alice Sluckin and Benita-Rae Smith (2016)

Revised Shirley Landrock-White (November 2018)

References:

icd.who.int (Accessed 6/11/18)

The Selective Mutism Resource Manual 2nd Edition, Johnson & Wintgens, Speechmark Publishing Ltd, London (2016)

Tackling Selective Mutism, Smith and Sluckin, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London (2015).

Copyright 2018 SMIRA

SM Professionals Leaflet

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

Selective Mutism in Children

Help for Professionals from SMiRA

Selectively Mute children will speak in some situations, but be silent in others. This leaflet gives information about and strategies for dealing with the condition.

What is Selective Mutism?

Selective Mutism is a relatively rare anxiety disorder in which affected children speak fluently in some situations but remain silent in others. The condition is known to begin early in life and can be transitory, such as on starting school or on being admitted to hospital, but in rare cases it may persist and last right through a child’s school life.

These children usually converse freely at home or with close friends, but do not talk to their teachers. In more serious cases they may also be silent with their peers, but communicate nonverbally. Other combinations of non-speaking can also occur, affecting specific members of the child’s family. The child may have no other identifiable problems and make age-appropriate progress at school in areas where speaking is not required, although some children may exhibit delayed development in language and learning skills.

Selective Mutism is relatively rare, but there may be many children with the condition who are never reported, as they are not troublesome in school. Having such a child can be very distressing for parents, as they can feel blamed for the child’s mutism.

What causes Selective Mutism?

No single cause has been established, though emotional, psychological and social factors may influence its development. In the past it had been thought that these children were manipulative or angry, but recent research confirms an underlying anxiety. This may lead to other behaviours, such as limited eye contact and facial expression, physical rigidity, nervous fidgeting and withdrawal, in addition to non-speaking in certain situations.

Can the Selectively Mute child be helped?

Yes, but early identification is important, so that some form of intervention can be planned. The condition may not improve spontaneously and can become intractable. If the child is not speaking after a time of ‘settling in’, then an Educational Psychologist or a Speech and Language Therapist should be consulted.

How can professionals help the parents?

Parents can feel very stressed and will need to have a sympathetic and supportive listener with whom to talk.

Concerns about the child should be discussed with parents, so that a strategy involving both home and school can be established.

Parents should encourage but not pressurise the child to socialise and speak in a range of situations. The child should not be punished for non-speaking, as this will only increase anxiety, but should be praised for participation in social activities and for vocalising, i.e. speaking, singing, making noises in play.

How can professionals help the child?

Any educator involved with a Selectively Mute child has a crucial role to play in helping both the child and the parents. Recognising that S.M. is an anxiety response in the child should help to reduce the frustration often felt by adults when dealing with this condition.

No pressure to talk should be put on the child, but plenty of encouragement given to interact with peers. It is important to create an accepting and rewarding atmosphere in which the child feels comfortable, whether or not he/she talks.

Any form of non-verbal communication from the child should be accepted and encouraged, as this helps to build the positive relationships, which are so vital in overcoming this problem.

Obtaining an audio or video recording of the child speaking at home will enable an assessment of speech and language skills to be made.

Every achievement by the child should be praised and rewarded in order to help enhance self esteem.

A supportive attitude should be encouraged amongst peers, to avoid teasing or bullying and to challenge any labelling of the child as non-speaking.

Suggested Strategies

- If the child does not answer the register verbally, allow them to acknowledge their presence in other ways, e.g. a smile, a nod, a look, raising a hand.

- Encourage self-expression through creative, imaginative and artistic activities.

- Sometimes sit the child at the front of the group for a story, to encourage attention and involvement.

- In discussion and circle-times, give the child the opportunity to speak and be patient when awaiting a response.

- If the child is socially isolated, link them with other quiet, shy children, singly or in small groups.

- Play games involving interaction between pairs or the group, e.g. rolling a ball, pulling on quoits, rowing ‘boats’, ring games and rhymes.

- Try non-verbal activities which require expelling air and using the mouth, e.g. blowing out candles, blowing bubbles, blowing ping-pong balls with a straw, breathing on a mirror, blowing swanee whistles and recorders, mouth ‘popping’, tongue ‘clicking’, teeth chattering, drinking

through long curly straws. - Make noises for toy vehicles and animals in play situations or as sound effects for a story.

Introduce play with puppets, because the child may speak ‘through’ the puppet, especially

from behind a screen; masks may also be helpful. - Use musical instruments for fun and to allow the child to communicate through the

instrument; have a ‘conversation’ between two instruments; make a ‘band’ and march round

the room, taking turns to be the leaders. - Encourage participation in noisy games and rhymes with predictable language, e.g. “What’s the time, Mr. Wolf?”

- Use activities that focus on the senses, to develop the child’s self-awareness.

- Use a ‘Kazoo’, which requires the child to hum in order to make a sound.

- Try a ‘Chinese Whispers’ game.

- Try amplifying vocalised sounds with a balloon.

- Try talking into a recording device or a telephone.

- Let the child record speaking and reading at home, which can be played back at school, if the child agrees.

- Arrange some home visits, taking a book, toy or activity to use with the child.

- Arrange for the parents to work with the child in school at specific times.

These last three strategies are known as Person or Situation Fading. This technique involves starting with the person or in the situation where the child does speak and then gradually introducing other people or situations. The child is rewarded for speaking as he/she adjusts to the new person/situation. As the child’s confidence grows, the presence of the initial security source can be phased out. For a detailed programme see “The Selective Mutism Resource Manual: 2nd edition” (2016) by Maggie Johnson and Alison Wintgens (ISBN 978-1-90930-133-7).

Remember that the child must be given time to adapt and that changes may only happen slowly. However, if the child is still not speaking after three-six months of intervention strategies, then a further professional review should be sought.

Is S.M. associated with other disorders?

Selective Mutism may hide other educational or physical problems, so as much information as possible should be gathered, particularly regarding the child’s performance in situations in which they do speak.

Children whose Mother Tongue is not English may go through a period of silence as they absorb English, before speaking it; this is a developmental stage in language acquisition and not true S.M., although Bilingual children can be affected by Selective Mutism.

Where can I find support?

The Local Education and Health Authorities should be approached with concerns. Independent of these is SMiRA, a mutual support group for parents and professionals. It maintains a website and

Facebook group, a reference list of books and articles, produces leaflets, a DVD and the books ‘Silent Children’ and ‘Tackling Selective Mutism’, and holds conferences.

SMiRA is a support group for those affected by SM, parents and professionals. It was founded by Alice Sluckin, O.B.E., and is based in Leicester, U.K.

For further details, contact SMiRA Co-ordinator: Lindsay Whittington on 0800 228 9765

E-mail: info@selectivemutism.org.uk

Website: www.selectivemutism.org.uk

© Copyright 2017 SMIRA

What is SM? Leaflet for Primary School

Statement from SMiRA regarding the use of the term ‘Situational Mutism’

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

Statement from SMiRA regarding the use of the term ‘Situational Mutism’

Recently, SMiRA has had a number of enquiries about whether the term

“situational mutism” is now preferred over “Selective Mutism”. We are aware of some grassroots change and some trainers advising the use of ‘situational” as the preferred term.

We are releasing this statement to clarify our position, as the UK’s national charity for selective mutism.

Currently, “Selective Mutism” is the official medical term which MUST therefore be used in all diagnostic reporting and signposting . “Situational mutism” is not a recognised diagnosis and may make it harder for affected families to find support groups, access disability benefits and so on.

“Selective” is a medical term which means “some of the time; in some situations” as opposed to “pervasive” which means “all of the time; in all situations”. This is a different use of the root word “select” and does not imply “selecting” meaning making a choice.

It takes many years for labels like these to be changed by the World Health Organisation and other diagnostic manuals and is not done lightly. Whilst selective mutism remains the official term, it should be used. An explanation can be given to those who don’t understand, that SM is “situational” but they should then also be advised on the true meaning of “selective” as used in this context.

The use of different, unofficial names and labels for Selective Mutism, makes it harder to raise awareness, campaign, and educate people in how they can support people with the condition.

Until such time as there is an official change of name, SMiRA’s strong recommendation is the use of the official term ‘Selective Mutism’. People may wish to add “sometimes known as situational mutism”, especially if this is the family’s preference.

Summer Holidays – ways to continue progress

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

Summer Holidays – ways to continue progress

Written by Gail Kervatt M.Ed for the USA-based group SMG-CAN and reproduced here with her kind permission

Summer break conjures up thoughts of lots of “fun”. To most families summer break means fun at the beach and the pool, fun having barbeques with friends, fun visiting Grandma and Grandpa, fun on that special vacation, fun playing with siblings and neighbourhood friends, fun sleeping late!

However, for a selectively mute child, summer break also means a “break” in the school intervention to help the child overcome the anxiety induced mutism. It means a two month break in routine, a two month break in provided services, a two month break in socializing with the teacher and classroom peers within the school setting. The summer break often can result in a regression in progress, in the lowered anxiety in the school setting and in the coping skills that have been practiced during the school year .

Parents can prepare and take some steps early to make sure that progress continues in September from the point where the child left off in June. Here are some suggestions:

- Meet with your school principal in sufficient time to discuss placement for next year. Discuss teacher choice and children with whom your child relates. This is very important and you may have to insist upon your request being granted. You may want to meet with the new teacher and discuss their knowledge, strategies and feelings of having your child in their classroom.

- Once the placement is made, find ways to slowly introduce and acclimatise your child to next year’s teacher. This can be accomplished through the “key worker” who works with your child in a small group and through the classroom teacher. The “key worker” in the school can invite possible teacher choices, one at a time, to the small group setting to play a game with the group. The classroom teacher can invite possible teacher choices into the classroom to participate in group activities and/or reading groups. The classroom teacher can send your child with a friend to deliver notes to the possible teachers.

- Spend some time with your child and a new classmate on the playground and then in the new classroom where he/she will be placed. This can be done after school and during the summer. Ask your child to choose the desk where he/she would like to sit.

- Ask the new teacher to make an effort to communicate with your child during the summer. This can be accomplished with a welcoming note or postcard, a phone message and/or a visit to your home. Take your child to school during August to help the new teacher set up the classroom. There should be no pressure for your child to speak during these encounters.

- As soon as possible, get a list of the new class and arrange play dates often with children of your child’s choice. This way your child will enter the new classroom in September knowing there will be a friend or two there with him.

- During the summer break provide opportunities for your child to practice communicating in the “real world” such as at a restaurant, the snack bar at the park, the library or a store. Even if your child can only point to a menu choice or item in a store, continue to expose him/her to these situations. Also, it’s important to model appropriate social interactions for your child. You might want to read Angela McHolm’s book, Helping Your Child with Selective Mutism, which demonstrates how to set up a “communication ladder” and go from there.

Enjoy that summer break, a wonderful time to relax and be together doing fun activities, but continue to help your child to ‘rid the silence’.

The SM Child in School

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

The Selectively Mute Child in School

The Teacher’s Response

As Selective Mutism is relatively rare, many teachers will never have encountered such a child before and may have no idea how to respond. Recognising that Selective Mutism is an anxiety response, similar to a phobia, may help the teacher to better understand the child.

Negative responses by the teacher can include:-

- feeling threatened or frustrated at being unable to elicit a verbal response from the child

- modelling verbal responses, e.g. answering register, ‘over-talking’ for the child

- denying there is a problem or hoping it will clear up in time without any intervention

- pressuring, bribing, threatening, flattering or cajoling the child into speaking.

Positive responses by the teacher can include:-

- removing the pressure to speak from child

- removing the pressure to make the child speak from yourself

- trying to help the child feel secure and accepted as they are at that time

- working hard to establish a rapport and a good relationship with the child

- accepting any non-verbal responses or attempts to communicate

- linking the SM child with a small group of peers and a key adult

- encouraging social interaction and physical movement through games

- letting the child know that other children and even adults fear speaking at times

- seeking outside help from agencies, e.g. SNTS, EPS, and support groups like SMIRA

- working with the parents to make a ‘bridge’ between home and school.

The Teacher’s role

1. Early identification

- the condition may be manifested in school settings and rooted in the child’s anxiety over speaking in unfamiliar social settings and to unfamiliar people

- allow a ‘settling in’ period, but if the child is still not speaking even to peers after a term, action needs to be taken, because they will not “just grow out of it”

- early treatment produces good results quickly, but a long established pattern of silence is harder to break and needs a highly structured programme

2. Establishing a partnership with the child’s parents

- communication, honesty and trust are vitally important in learning about the child

- visiting the child at home can help in transferring speech to the school setting

- parents visiting school with child before entry, especially when the school is empty, can help the child to gain ‘ownership’ of the building before having to share it

- tape/video of the child speaking at home can be brought to school, if the child agrees

- friends from school visiting to play at home can also help in transferring speech.

3. Effecting Intervention

- assess child’s stage of communication, e.g. non-verbal, sounds, single words, phrases

- plan a strategy to move the child on to the next stage

- use Stimulus Fading* (‘sliding in’) technique, if a conversation partner is available for child

- use Shading technique* if no existing conversation partner is available

- use Interactive Therapy Group games with young children in school

References

Johnson, M. & Wintgens, A. (2001) “The Selective Mutism Resource Manual”.

*p.117-204 Speechmark Publ. Ltd. (ISBN 0-86388-280-3)

Roe, V. (1993) ‘An Interactive Therapy Group’ in “Child Language, Teaching and Therapy” Volume 9, Number 2, pp.133-140

© Victoria Roe. November 2003

Interactive Therapy

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

How can I help children who are shy, socially isolated or even selectively mute in school? This was the question I faced when my school’s SEN screening system identified a large number of such children a few years ago.

Drawing on ideas from Speech, Movement, Music and Drama therapy, I put together a programme for small groups. This was implemented during school time, for 20 minute sessions several times a week.

The aims were to provide a relaxed environment in which all forms of communication were accepted and encouraged, to encourage relationships between a limited number of children, to provide chances for the children to experiment with being loud and to make the sessions an enjoyable experience.

I adopted the role of a senior group member, initiating ideas, building on their ideas and participating in the games with the children. The content of the sessions was varied but each contained several different activities.

The games involved individuals responding to me or each other, pairs work between the children, and whole group activities. Games like rolling balls, boats and quoits pulling helped develop eyecontact.

Activities like parcels, statues, sliding and swinging developed trust. Musical instruments and puppets (especially squeaky puppets) allowed the children to be legitimately noisy, something they do not normally have a chance to do in the classroom.

All the children involved in such groups over the years have benefited from the experience, becoming more confident and better able to relate and communicate. A few selectively mute children have begun to speak as a result of sharing in the Interactive Therapy Group sessions.

Victoria Roe – Teacher (SENCo)

Leicester

© Victoria Roe & SMIRA 1998

Phonics Testing

Below is a link to a pdf document regarding Year 1 Phonics Test from The Communication Trust:

“Communicating Phonics – A guide to support teachers delivering and interpreting the phonics screening check for children with speech, language and communication needs”

Guidelines for Nursery & Pre-School

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

Shy and Selectively Mute Children of Nursery Age

Guidelines for nurseries and play-groups

1. When parents approach play-group leader/nursery supervisor it is useful to ascertain present language level, i.e. how long has child been talking and whether he/she talks away from home, to other children or strangers, or other members of the family. Is the child considered shy and are there perhaps others in the family who are also shy?

2. If there is non-speaking with strangers the play-group leader might suggest visiting the home prior to the child commencing in the nursery. It might be necessary to repeat this several times to enable the child to get to know at least one person from the nursery. Also, it would help if the child got to know at least one child or more currently attending the nursery so they do not feel a total stranger.

3. Selective Mutism is nowadays considered a sign of anxiety, not a form of stubbornness as viewed in the past. Therefore, once the child has been admitted, no pressure should be put on the child to talk, but plenty of encouragement given to interact. It is important to create an accepting and rewarding atmosphere in which the child feels comfortable, whether he/she talks or not. Accept that he/she may not like to make eye-contact, as SM children often find this threatening.

4. If the child does not answer the register, find other ways of acknowledging his/her presence with a smile, i.e. accepting a nod, shaking hands, let the child put his/her hand up when their name is called.

5. SM children lack social skills and may get overwhelmed in the rough and tumble of the room. Often they stand rigid and find it difficult to get a friend. Try to get him/her to pal up with a quieter child, preferably one at a time. The two might play together with the Wendy House or on a slide. Phase in others when the relationship has been established.

6. Encourage artistic expression through clay, etc. Make sure the SM child has paintings or art-work to take home to show parents and siblings. Also, it might be useful for the SM child to bring their favourite toy from home to the nursery.

7. At story time get the SM child to sit close to the front, occasionally turning to him/her. Observe how the child reacts to (a) funny aspects and (b) sad bits.

8. Introduce play with puppets. These can be useful, particularly if the child is able to talk from behind a screen.

9. Some SM children are particularly good with jigsaws and they then like being praised.

10. Encourage noisy games, musical instruments, etc. i.e. beating the drum and blowing a trumpet.

11. Observe whether the child is willing to go to the toilet at play-school and eat or drink during breaks.

12. Observe posture and facial expression. SM children tend to look unhappy and often do not stand straight.

13. Use techniques as outlined by Victoria Roe (1993) which draw on speech, music and drama therapy. (Further details from SMIRA).

14. Remember that these children must be given time and that changes will come about imperceptively slowly.

15. If, after 6 months in the play-group, the child is still not talking, look around for help.

16. Always remember that the non-speaking may hide other educational or physical problems.

References:

Roe V. (1993) An Interactive Therapy Group

Child Language Teaching and Therapy Vol. 9 2 1993 pp. 133-140

Alice Sluckin/SMIRA/1999

Helping SM Students in Secondary Schools – Staff Guide

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

‘What is useful for staff in secondary schools to know about helping

teenagers with Selective Mutism? In their own words:

a summary of interviews with teenagers who went on to be able to talk’

Libby Hill, Speech and Language Therapist at Small Talk

To read the rest of the report please click on ‘Open’ or ‘Download’ below:

Why Doesn’t This Child Talk? (for teachers and youth group leaders)

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

For Teachers and Youth Group Leaders

Why Doesn’t This Child Talk?

He or she has an anxiety disorder called Selective Mutism

Children suffering from selective mutism (SM) become mute in some social situations and CANNOT utter a sound

- Selective Mutism is a form of social communication anxiety disorder, which leads to difficulty with some social interactions.

- These children typically may not be able to speak, laugh out loud, make any noises, or move their lips in the school environment with both their peers and adults, despite speaking normally and fluently at home, in familiar settings and with familiar people.

- They are often also unable to initiate any social exchange and may be reluctant or slow to join in.

- They typically try to avoid, or are very slow to respond, in situations where they feel they are expected or required to speak.

- Some, but not all, children may also have difficulty smiling or making eye contact, and their body language and facial expressions may be rigid.

- These children are often very sensitive, alert and self aware, with high respect for rules and authority; they are non-disruptive and can be easily overlooked in the classroom by peers and adults alike.

- These children are NOT usually unhappy, shy and quiet; often they are quite the opposite when feeling relaxed!

- They are NOT rude, purposely ignoring you, or trying to get attention.

- Their behaviour is NOT due to wilfulness, stubbornness or manipulation.

Anxiety and fear can literally make it impossible for these children to speak.

For more information about Selective Mutism, please visit www.selectivemutism.org.uk

How to relate to a child with Selective Mutism

- DO convey to the child that you understand their difficulty and you are happy for him or her to speak when they feel ready.

- DON’T try to make the child speak or ask why he or she is not talking….this will only increase anxiety!

- DO provide many opportunities for speech to happen but remove from yourself and the child any expectation for him or her to speak.

- DO talk to the child normally but don’t expect a response right away.

- DO use comments, statements, and rhetorical speech to elicit a response rather than direct questions.

- DON’T ask open-ended questions; instead phrase questions so that the child can respond non-verbally; choose YES/NO questions or questions where a one or two word answer will suffice.

- DO minimise eye contact; play side by side rather than facing the child; a low-key, matter-of-fact and a silly/fun approach works best!

- DO make him or her feel included and valued by encouraging their non-verbal participation in ALL activities; try to give him or her responsibilities and tasks that they can feel proud of doing; give lots of praise and reward these accomplishments.

- DO build a closer rapport with the child by getting down on the ground to play at their level and finding out what subjects really interest him or her.

- DO stand up for the child when others ask why he or she isn’t speaking; make sure everyone knows the child can speak at home and when ready he or she will also speak at school.

- DO watch out for any bullying as these children are vulnerable and cannot stand up for themselves.

- DON’T act surprised or ‘make a big deal over it’ if the child does begin to speak, as this may embarrass them and cause a setback.

Just enjoy, have fun and get to know the selectively mute child, who has so much to say, is keen to talk, but needs some time, help and encouragement from you to relax and to be able to do it!

SMIRA – Selective Mutism Information & Research Association

www.selectivemutism.org.uk

Autism vs SM – similarities, differences and overlap

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

Autism vs SM – similarities, differences and overlap

To read the rest of this document please click on ‘Open’ or ‘Download’ below:

SMIRA Conference Presentation Northamptonshire NHS SM Pathway BS and HW

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

SMIRA Conference Presentation Northamptonshire NHS SM Pathway BS and HW

To read the rest of this document please click on ‘Open’ or ‘Download’ below:

Letter templates for young people and adults when writing applications, formal letters etc

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

Letter templates for young people and adults when writing applications, formal letters etc

Is your selective mutism (SM) holding you back at work or in your educational setting? Do you find it difficult to communicate effectively with your GP and other services? Would you like your supervisor, employer, course tutor, interviewer, health practitioner or link worker to understand your SM?

A carefully worded letter or email could be your best way forward. You can explain SM as it affects you in this particular situation. You can also ask for certain allowances to be made to ensure you have as good an experience as possible. The law calls these allowances ‘reasonable adjustments’.

By putting all this in writing, you have a document you can use to protect yourself in case of unfair treatment or discrimination.

There’s a template on the next page which you can tailor to fit your circumstances, but first spend a few moments writing down what you want your letter or email to achieve. You can then use these notes to make sure your letter captures what you want to say.

Click Open to see the full document or Download to download it to your computer.

Please click ‘Open’ or ‘Download’ below to see the whole presentation as a pdf.

Selective Mutism Bibliography

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

Books and Articles on Selective Mutism

N.B. Although this list is extensive, it is not exhaustive. Researchers should conduct their own document searches, especially for more recent publications.

This document contains listings of books and academic publications – please click on ‘Open’ or ‘Download’ below to access the full document.

SMIRA Articles Archive

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

SMIRA Articles Archive

Paper versions of articles stored by SMIRA and donated from Cline, A. & Baldwin, S. (2004) ‘Selective Mutism in Children. 2nd edition.’ London: Whurr. Roe. V. (2011) ‘Silent Voices Research Project’ and Alice Sluckin. Copies on request for printing/postage cost.

Please click on ‘Open’ or ‘Download’ below to access the full document.

Selective Mutism Bibliography by Category

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

Books and Articles on Selective Mutism by Category

N.B. Although this list is extensive, it is not exhaustive. Researchers should conduct their own document searches, especially for more recent publications.

This document contains listings of books and academic publications arranged by category – please click on ‘Open’ or ‘Download’ below to access the full document.

Leaflets from the Selective Mutism Resource Manual (2nd Edition)

—

Video chat – small steps

We are posting this link to Maggie Johnson’s resource at the top as it is especially relevant for online therapy at the moment:

Do’s and Don’ts at Pre and Primary School

Do’s and Don’ts at Secondary School

Transition Plan

TRANSITION PLAN

Preparing to change School, Class or Teacher or start at school or nursery

Time invested in agreeing and implementing a Transition Plan will ensure that the child adapts quickly to a new environment, builds on progress made and develops in confidence and independence.

A change of class and/or teacher can be a stressful time, particularly if a child is doing well and parents are afraid of losing momentum. However, if the transition is managed well, children can leave old memories and associations behind and gain confidence and independence in the new setting.

The following recommendations also apply to starting school or nursery for the first time.

1, It is vital that all staff in the new setting understand the nature and implications of selective mutism and that there will be no pressure on the child to speak until they are ready. Reassurance should be given to the child to this effect, both by parents and staff (see Phase 1 intervention for relevant information). Identify a learning mentor / keyworker / support teacher in the new setting who will provide an escape route if necessary and meet with the student regularly to ensure they are happy, not being teased/bullied etc.

2. Preparation should start several weeks in advance with positive comments about the move and familiarisation with the building, classroom and staff.

eg:

- social visits with parents for summer fair, concerts, charity events, play schemes etc

- look round school/class when building is empty (during holiday or after school)

- take photos and make a booklet about My New Class/School

- meet the head and classroom teacher/key staff in as informal a situation as possible.

- include younger siblings if available and appropriate.

- routine visit with current class plus one extra visit with familiar adult or friend

- new teacher/teaching assistant (TA) to visit child in current class or at home. (Home visits likely to be extremely beneficial – SMRM page 131).

- slide-in new teacher/TA before end of term (Phase 2 intervention)

3. If it is not possible to meet new staff in advance, try to ensure continuity by

eg:

- keeping the child with a best friend

- arranging for previous teacher/TA to spend some time with the child on their first day

- ‘borrowing’ previous keyworker to hand over to new keyworker at beginning of term (Phase 1 or 2 intervention)

- keeping current keyworker (but beware of child becoming too dependent on one adult over a long period of time)

4. It will be helpful if new teachers/teaching assistants (TAs) can make some time for a few minutes of rapport-building with the child on a one-to-one basis during their first week in order to achieve as many of the following as seem appropriate:

eg:

- reassure the child that they will not ask them questions or pick them for demonstrations unless the child volunteers

- enlist the child’s help and then praise for a job well done

- reassure the child they will be checking they are OK, have a friend to sit with, understand the work, have been to the toilet etc.

- give the younger child confidence to respond by playing games that initially only require pointing, nodding, shaking the head etc.

- reassure older children they can contribute/ask questions by writing things down until they feel relaxed enough to talk.

- explain that they will need to use a loud voice sometimes but this does not mean they are angry (SM children are very afraid of getting things wrong and will withdraw rather than risk being told off).

5. Foster friendships with other children as actively as possible, particularly outside school by inviting peers home to play/have tea. Try to find out in advance if there are children nearby that attend the same school/playgroup and make contact with their parents. Teachers can help by suggesting which children would make good friends and introducing parents after school if parents find it difficult to make the first move.

6. Parents should stay with children in pre-school settings until the child is comfortable for them to leave. Do not EXPECT the child to be anxious, as this anxiety will be conveyed to the child. Parents need to stay relaxed and calm themselves and praise the child for being brave and staying on their own for longer each day. Do not delay the initial separation too long however, as it is only by facing their fear and successfully coping on their own that children will learn not to be afraid.

7. If children are finding it hard to join in at pre-school/reception class, parents can come early and join in the last few activities/story with the child so they leave with a positive experience. Alternatively, a parent can stay for the first half an hour, joining in the activities and helping the child to integrate/make friends/build rapport with a designated adult (SMRM page 132). This may occasionally be necessary in Year 1/Year 2.

8. Pupils preparing for transition to secondary school or college need to focus on developing their independence outside school and confidence in talking to strangers as much as possible during their final year, e.g. making phone calls, running errands, dog-walking, ordering pizza, banking birthday money, earning money car-washing and baby-sitting, going swimming, joining clubs, developing interests etc. etc. (SMRM page 170). The summer holidays are a good time for shared activities and trips with friends who will also be attending the new school/college, and for meeting new people who know nothing of the child’s difficulties. Confidence grows through achievement and as the child becomes their own person, the seeds can be sown that a fresh start in a new educational establishment is exactly what they need. If they can talk to strangers, they will be able to talk in a new environment.

• See Danielle aged 15 in BBC Documentary ‘My Child Won’t Speak’

SMRM = Selective Mutism Resource Manual, Johnson & Wintgens, 2001, Speechmark Publishing Ltd.

Copyright Maggie Johnson 2011.

Planning and Managing Intervention with Small-steps Programmes

Implementing a small steps programme

The majority of selectively mute children have developed a chronic anxiety reaction in situations where they are required to talk to people for the first time, especially when they can be overheard (a phobia of speaking). As a result, they have a very limited talking circle and are only able to talk to certain people in certain situations.

Following assessment, all work to overcome this type of difficulty starts with ensuring that people in the child’s school/home environments understand:

a) what to do to encourage communication and the confidence to try new things, and

b) what is unhelpful and maintains the mutism.

This might be achieved by arranging a meeting in school with parents/key staff using the Silent Children DVD(*1) as a springboard for discussion and information-sharing, both in general terms and in relation to the individual child. One crucial step will be to begin talking to the child with open acknowledgment and explanation of their difficulties.

For younger children, a change in other people’s reactions and expectations, together with encouragement and support to enjoy non-verbal communication, can be sufficient to facilitate a progression towards verbal communication. When no change is noted however, selectively mute (SM) children are likely to benefit from a more formal behavioural programme designed to reduce their anxiety and extend their talking circle.

Such programmes use three behavioural techniques to elicit and generalise speech:

a) ‘stimulus fading’

It is the audience/conversational participants or setting which changes rather than the child’s speech effort. The child talks to a trusted conversational partner (usually a parent) in a minimal anxiety situation and then one factor is changed – an anxiety trigger is introduced. If the child is relaxed to start with and the change is only slight, the child can tolerate the anxiety trigger and keep talking. For example they can tolerate another person gradually coming closer and joining in the activity.

When this is carefully planned and broken into very small steps we call it ‘the sliding-in-technique’. At first the child talks freely to a member of their family with the keyworker outside the room; this is repeated with the door slightly ajar, then with the door open and finally with the keyworker inside the room. If the child is able to maintain some voice at this stage, the keyworker can move forward and join in the activity. Direct eye-contact is generally avoided until the child is talking more confidently. The process is further facilitated by setting specific targets and starting with very short, undemanding turn-taking activities, such as counting to 10, which are gradually extended to longer sentences. Specific target-setting is only appropriate for older children who understand the principles involved and are motivated to overcome their difficulties, having reached a point where the selective mutism has become well entrenched and beyond their control.

b) ‘shaping’

It is the speech target that changes. The child starts with non-verbal communication with a keyworker in a minimal anxiety situation and then takes tiny steps towards verbal communication by gradually increasing articulatory effort, voicing, eye-contact, syllable-, word- and sentence-length etc.

c) ‘desensitisation’

The child gets used to the thought of doing something they previously believed they couldn’t manage by carrying out related, but less-threatening activities. For example they allow a teacher or classmates to hear their voice on tape. Or they talk to a classmate over the phone before trying it face to face.

Stimulus fading or shaping?

In practice we use a combination of techniques depending on the age of the child, how anxious they are and whether the parent(s) can be involved. Desensitisation activities can play a valuable part in both stimulus fading and shaping programmes but should never be allowed to become a substitute for speech.

a) Up to 6-7 years

Shaping works very well with the very young or less anxious SM child and leads on from rapport building with a familiar and trusted staff member (keyworker) in the child’s school setting. The children benefit from both individual and group sessions where they feel absolutely no pressure to talk, but are gradually encouraged to move from non-verbal communication and action-rhymes, to sound-making, singing, humming, speech sounds and words. At the same time, parent(s) spend time in the classroom/playgroup and at home using the stimulus fading principle to help the SM child speak near to, and eventually with, other children and adults. Other professionals (speech and language therapists or psychologists) have a valuable role with overall coordination, supervision and support. As they can represent an extra pressure, they should avoid direct involvement with the child unless there are other concerns about the child’s language development, learning, behaviour, or family dynamics.

a) parent supports generalisation to other people and places and slides out as child’s confidence grows (omit this step if parent not available)

b) rapport-building with keyworker

c) shaping games with keyworker to elicit speech

d) keyworker/parent supports generalisation to other people and places including transition to new school/class

b) 5-6 years and above

After working through the above strategies, more anxious children may need a specific programme to elicit speech with a keyworker. They need to feel in control of their anxiety, so are made fully aware of each target and record their success at each step. Stickers etc. are a confidence boost and provide a natural break which reduces the anxiety level between targets. For most children, stimulus fading with the parent provokes far less anxiety and yields quicker progress. Some teenagers find it difficult to work in front of their parents and prefer shaping however. And sometimes there is no talking partner available so stimulus fading is not an option.

How often and how long will it take to elicit speech?

A shaping programme to elicit speech should only be attempted if the child can be seen individually for a short time three or more times a week for at least a term without a break.

Any less than this and it’s like starting again each time for the child.

Stimulus fading also needs a commitment of three sessions a week with close collaboration between home and school or clinic, but speech is usually elicited with a familiar keyworker after 2-4 sessions. Once the child is talking comfortably to the keyworker, sessions need to continue on a twice-weekly basis to slide-in other significant adults and children and transfer back to the classroom. Once talking in the classroom, targets can be managed within the school day and extra sessions need only be arranged to manage transitions from one year group to another.

Transitions between schools and classes must be carefully managed as part of the programme. It is relatively easy to elicit speech with key adults and friends, but generalisation to other children and adults in all situations can take several years, depending on the age and anxiety levels of the child. What we can be sure of is that the earlier we start and the more we do, the quicker the difficulty will be overcome.

Specialist involvement?

Sometimes it may be appropriate for an outside professional to establish speech with the child in the first instance – for example a speech and language therapist may already have established rapport with a child during assessment, or be able to capitalise on a holiday period to get a programme underway in preparation for a new term. Or the child may have put up so many barriers at school that they need to gain confidence and belief that progress is possible on neutral ground. Equally, therapists and psychologists will benefit from the experience of working with at least one SM child in order to advise and support more effectively in future. But whichever approach is chosen, it is essential to find or hand over to a keyworker in the child’s school as soon as possible. Only staff on site have the day to day contact necessary to sensitively and effectively manage the generalisation phase.

If a school-based keyworker has been identified:

a) elicit speech with keyworker at home or at school using sliding-in technique with parent or shaping programme

b) fade out the parent either at home or school so that child can talk to keyworker without parent present (omit if parent not involved)

c) keyworker facilitates generalisation to other people and places at school including transition to new class/school

d) when half the class have heard child’s voice, conduct activities during class time

parent supports generalisation in wider community

If the keyworker has to be a parent (not ideal but sometimes unavoidable):

a) parent visits school regularly to slide-in selected children and adults in a room where they will not be disturbed, and slides-out for part of the session as child’s confidence grows with new people

b) new adult (e.g. teacher) introduces new activity while parent is out of the room

c) if possible, new adult starts next session and parent arrives later to take over

d) parent transfers activities to the empty classroom

e) parent continues generalisation to other people and places including transition to new class/school, always sliding out for part of session.

f) when half the class have heard child’s voice, conduct activities during class time

g) parent supports generalisation in wider community

If the initial keyworker is not school-based:

a) elicit speech with keyworker A at home, school or clinic using sliding-in technique

b) slide out the parent either at home, school or clinic so that child can talk to keyworker A without parent present (or do this after next step)

c) keyworker A hands over to a school-based keyworker B

d) slide out keyworker A

e) keyworker B facilitates generalisation to other people and places at school including transition to new class/school

f) parent(s) support generalisation in wider community

Full details of target-setting are set out in ‘The Selective Mutism Resource Manual’ (SMRM)*2.

Common practices that prevent or hinder progress

Firstly it must be stressed that although there are many factors that can impede progress, they can all be resolved or avoided! It is never too late to repair the situation after a setback, with open discussion between all involved to identify and modify the relevant factors.

1. The programme was started too early.

Inadequate assessment may lead to an inappropriate diagnosis and/or intervention plan.

a) The child may have additional problems such as autistic spectrum disorder, attachment disorder or receptive language difficulties which need to be addressed alongside the mutism.

b) Their reluctance to speak may be due to cultural or personal inhibitions which need to be addressed in the first instance.

c) Factors at home or at school which may be reinforcing the child’s mutism or raising their anxiety may not have been fully explored and addressed.

It may be helpful to revisit the child’s speaking habits and to use the Parental and School Interview forms in the SMRM(*2) as a tool to obtain more information about other concerns and possible maintaining factors.

2. Lack of teamwork, information or support.

Insufficient time has been invested in information sharing, joint planning and monitoring, leading to loss of momentum or the programme being abandoned.

An on-going team-approach involving both home and school is paramount and will be flagged up again in point 5, for any unaddressed anxiety or inconsistent handling will undermine the effectiveness of direct work with the child. Even when parents are not able to contribute to the programme directly, every effort should be made to forge a home-school link as parents can provide information, ideas and back-up that are crucial to the overall success of an intervention plan.

It must also be recognised that working with SM children is emotionally draining and keyworkers need ongoing support and regular opportunities for reviewing progress and sounding out ideas with the school SENCo, class teacher or visiting specialist. Outside agencies should note that leaving a programme in school without building in this support is rarely successful. Inexperienced keyworkers will need help to plan targets with encouragement and reassurance to maintain momentum. Never put the onus on a keyworker to make contact only if they have a problem, as this implies failure if the need arises. Review meetings should be set in advance and then cancelled if not required, with additional telephone contact arranged within a week or two of leaving a programme. Aim to review progress once a month for the first term and twice a term thereafter. By the second year, once a term is usually sufficient but contact can be maintained between meetings via telephone or email.

3. There has been inadequate discussion with all involved about the nature of intervention and the time it is likely to take.

Some schools may not have been aware of the time commitment required to successfully address selective mutism, nor appreciate that a relatively small time investment now, will eliminate the need for prolonged intervention and anxiety in later years. Other schools may be committed to the long haul but have allocated a keyworker to the child for only one or two over-lengthy sessions per week.

Frequent 10-15 minute individual sessions will be required to establish speech initially

(minimum three times a week), with a gradual reduction in frequency in the generalisation phase (sessions can now be increased to 20-30 minutes). Generalisation to other people and situations, and the transitions into new classes and schools must be managed as part of the intervention plan.

4. The child is not an active partner in the intervention process.

i) There has been little or no discussion with the child about the nature and resolution of their difficulties. Never ask children WHY they do not talk – how can they possibly know why this is happening to them?! All they know is that talking fills them with dread and they will do anything to avoid that feeling.

Instead, TELL them why. Before embarking on a programme, children need reassuring that you understand why they cannot talk in certain situations and know they are not doing it deliberately – it is anxiety that is stopping their voices from coming out of their mouths. Go on to tell them that this anxiety developed when they were much younger – they got scared when first separated from parents/teased for speaking/found it hard to use a new language/felt different or awkward in a new/noisy/crowded environment etc.

Explain that this happens to lots of children and it’s nothing to worry about – as they get older and braver the anxiety will disappear.

ii) There has been insufficient reassurance that progress will be made by moving one small step at a time at the child’s pace. The child therefore has no sense of where each activity is heading, leading to heightened wariness and anxiety. Do not fall into the trap of thinking you can fool SM children into talking or that it is somehow kinder to avoid explanations! They can only control their anxiety by knowing exactly what is happening and what is about to happen.

Breakdown at this stage often leads to a sense of being ‘tricked’ into talking and a dread of further consequences. Many children fear that if they talk to one person, they will immediately be expected to speak to everyone else as well – the secret will be out! They need to hear from everyone involved – parent, keyworker and teacher are the usual minimum – that time is NOT the essence, and that they can get used to talking to just one new person at a time. Only through trusting that what the keyworker says will happen, actually does happen, will children be able to relax sufficiently to take new risks. For example, if told they will be working alone they need to see a ‘Do Not Disturb’ sign on the door, rather than worrying that someone will come in at any moment. They should be given opportunities to help plan their programme.

5.There has been a lack of overall co-ordination with consequent inconsistency for the child.

For example, if the child has been assured that everyone at school understands their difficulty and that they need only talk to their keyworker for the time-being, valuable trust can be lost if other staff try to elicit speech. Or if one person is offering money, chocolate bars or Happy Meals for achieved targets, it should not be surprising that someone else’s stars appear less exciting.

It is worth emphasising that rewards are a valuable incentive – they are fun to win and provide tangible evidence of progress – but they are NOT bribes. The value of a reward lies not in its material worth, but in fostering the child’s belief that success IS possible with an opportunity to enjoy that success.

6. There is a poor relationship between the child and designated keyworker.

Young children need very regular contact with a keyworker in a familiar place to gradually feel comfortable and confident in their company. Sessions therefore need to be either at home or school in the early years with an appropriate adult who is part of the child’s day to day routine.

Perhaps there has been insufficient time to develop rapport before attempting the sliding-in technique or the keyworker has little understanding of the condition and conveys impatience or insensitivity. Sometimes the keyworker has not been particularly sympathetic to the child in the past and the child has a clear memory of this. A genuine apology and fresh start can work wonders!

7. The child has no clear indication about how often sessions with a keyworker will take place or how long they will last.

There is no warning that sessions are about to take place and no explanation if sessions are missed. Or there is a rather ad hoc approach to the sessions with no agreed time-limit (10-15 minutes recommended). SM children need to know exactly what is happening, otherwise they worry which is counter-productive to ‘having a go’ and taking risks. Many selectively mute children have a heightened sense of ‘abandonment’, and it is vital they believe that, all things being equal, their keyworker is not going to let them down.

8. The child is not clear about the content of the sessions/the keyworker is not clear about the child’s limitations.

The keyworker is attempting to build rapport through general chat rather than specific target-setting activities. This is appropriate for shy children but not SM children for whom social conversation carries the highest ‘communication load’ and generates acute embarrassment when they cannot respond. Provide an outline of the session (e.g. 10 minutes on targets, questionnaire about bullying, check to see how coursework is going) and give students the option of choosing the order (they may prefer you to choose). Younger children may simply be working on targets.

9. The programme has come to a standstill.

The child is enjoying the keyworker’s attention but little or no progress is being made. Perhaps the keyworker lacks confidence and is holding the child back by their own fear of failure. They are repeating tasks excessively rather than moving on each time. Or perhaps the keyworker is getting a boost from the unique relationship they have built with the child, and is sub-consciously delaying the generalisation phase while genuinely believing that the child cannot cope with more pressure.

Sometimes children are given too much control and are allowed to set not only the pace of the programme, but also the content. They then avoid taking risks and choose to repeat ‘easy’ anxiety-free activities. It is important for children to be given options, but only within an overall structure or progression which has been set by the keyworker.

In order to move the programme forward, the keyworker may need to reiterate their role (point 4) and remind the child that they are there to help the anxiety (‘nasty feeling’) go away so that the child can have friends and fun, get help with their work and so on. The phrase ‘I can’t do that because then I wouldn’t be helping you’ is a useful one to have ready! Keep the child’s favourite activities for rewards rather than time-fillers, and terminate sessions early if the child is not ready to try something new (see point 12).

10. The rule of changing only one variable at a time when setting a new target has not been adhered to.

The child is being expected to cope with too many changes at once. Variables include the identity of those present, the number of people present, the location, and the task.

If new activities are carried out within earshot of other people, perhaps through an open window or door, this alone represents a significant change for the child. Similarly, if group-size is increased, it is unreasonable to expect the child to cope with a change of activity at the same time. Either the number of people present should be increased or the complexity of the activity, but not both together.

So, if succeeding in a withdrawal room with the keyworker, the next step should be to either repeat the same activity in the classroom with no-one else present, or to repeat the activity in the withdrawal room with an extra child or adult of the child’s choosing. Or if the child talks to a teacher at home, they could try the same thing at school in an empty classroom with a parent present. Repeating the activity without the parent is a separate step.

11. Only one variable has been changed but it has been too big a step for the child.

How can the step be made smaller? Many factors can influence anxiety levels, so it is important to understand which factors are operating for a particular individual. For example, does it make a difference if the listener looks at the child or is turned away, if the child is required to silently mouth or use voice, or if a visible or hidden articulatory movement is involved (as in ‘p’ vs. ‘s’)?

More detail is given in the SMRM2, but essentially the keyworker should try to reduce or modify one or more of the following factors:

- the choice of person present

- the number of people present, either as part of the task or hovering in the background

- the extent of physical involvement (articulatory effort, eye-contact and gesture)

- the length of the task (keep it short and specific rather than open-ended: ‘read 5 words’ or ‘read for one minute’ cause far less anxiety than ‘read to me’)

- the ‘communication load’ of the task itself

The communication load is low when using rehearsed or familiar speech, minimal responses and factual language, and high when a child is required to initiate, express opinions, use complex language or hold open-ended conversations.

With regard to the choice of person present, care must be taken to ‘slide-in’ the child’s teacher at the appropriate time. If the child has little rapport with their teacher, sees them as an authority figure, is afraid to fail or wants to succeed almost too much, their anxiety level may be too high to allow the sliding-in technique to be successful. They will gain more confidence if the keyworker slides in a child or less ‘threatening’ adult first. Sometimes the child has such strong associations of failure with their current teacher, having tried to speak and failed on many occasions, that it is better to develop their communication with a classroom support worker in the first instance, and work towards generalising speech to the teacher in the next year group.

12. The child is being rewarded for silence rather than communication.

The child has failed to meet a target but was still rewarded – either with their usual token ‘for trying’ or by spending the remainder of their special time with the keyworker repeating anxiety-free activities. This reinforces silence and lack of risk-taking, and leads the child to view the keyworker as someone nice to spend time with, rather than someone who is there to help them move forward (see point 9 for related discussion).

Children should never be allowed to feel they have failed – only that their anxiety was too great to allow them to succeed. The keyworker’s job is to make the steps toward a challenging target smaller, giving reassurance that this will make it easier for the child to manage. This can either be done immediately with a shorter or simpler task (see point 11), or by terminating the session early with a very casual “Never mind, we’ll try again next time”. The experienced keyworker will use both these options to the child’s advantage, but less experienced workers are advised to opt for early termination. This provides breathing space and planning time, and means the child will feel disappointed that the session is over, rather than relieved that the pressure is off. If they have a good relationship with their keyworker (point 6) they will look forward to the next session, remaining motivated to attempt activities or discuss other ways forward. Fixed times for the sessions (point 7) ensure that the end is always in sight and that both child and keyworker usually finish ‘on a high’.

13. The child has been moved through the programme using a whispered voice.

Generalisation will be significantly delayed if this is the case, for whispering indicates audience-awareness and extreme tension around the vocal cords. It will be necessary to back-track with the sliding-in technique, moving more slowly (see point 11) so that a quiet but audible voice is maintained throughout, reminding the child to ‘use big voice’ or ‘switch voice-box on’. For example the keyworker may need to enter the room backwards to prevent reversion to whispering, or join in talking games while still outside the room. As long as the child is relaxed, volume then usually increases naturally as short manageable tasks are achieved and confidence grows. Activities involving silly noises and humming may also be helpful, as are blindfold or barrier games where the keyworker cannot lip-read and says ‘Pardon?’ if unable to hear.

N.B. It is perfectly acceptable for children to whisper at other times outside the special time allocated to working on targets. Any communication in natural settings is to be accepted until the programme helps them to feel better about using a stronger voice.

14. The programme has been discontinued too early with not enough attention paid to transitions.

It cannot be assumed that once a child is talking to one or two people they will now improve spontaneously and transfer easily to a new class or school. Change can sometimes be an advantage as mentioned in point 11, but for most children the generalisation phase needs to be closely monitored and facilitated. Prepare children for transition by introducing them to a new school or teacher in the term before the move, and take advantage of school fetes, informal visits and existing friendships to establish positive links and associations. Examples that help children settle include exploring and talking in a new school when it is empty, looking forward to sitting with a friend in a new class, having the continuity of a support-worker across two year groups, and being visited by a new teacher before the transfer for rapport-building and sliding-in.

Maggie Johnson

Speech & Language Therapist Advisor

Alison Wintgens

Consultant Speech & Language Therapist

(*1) Silent Children: approaches to Selective Mutism, 24 minute DVD made with grant from DfES, available from SMIRA, email: smiraleicester@hotmail.com.

(*2) The Selective Mutism Resource Manual, Maggie Johnson and Alison Wintgens.

Speechmark Publishing, 2001, ISBN 0 86388 280 3.

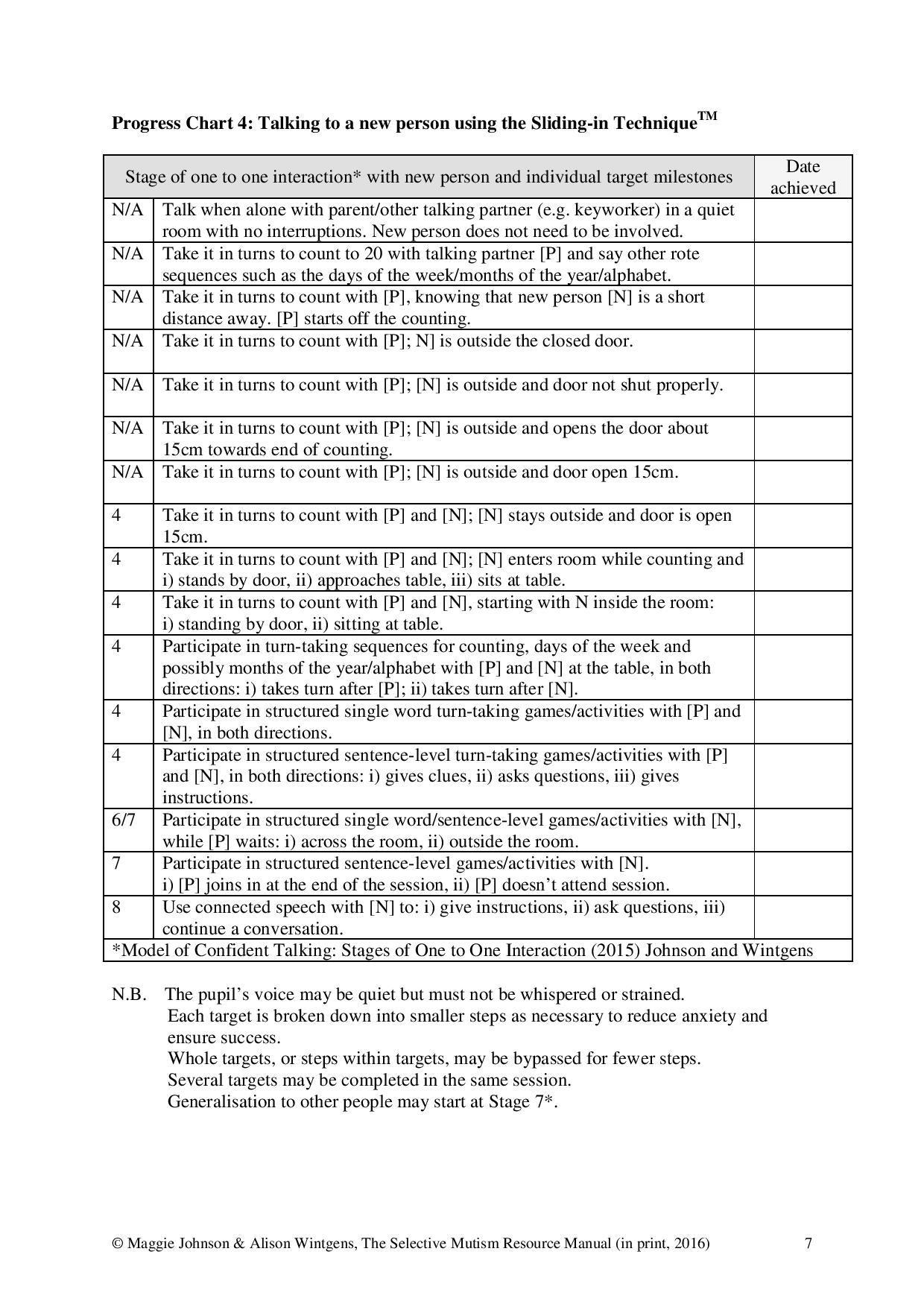

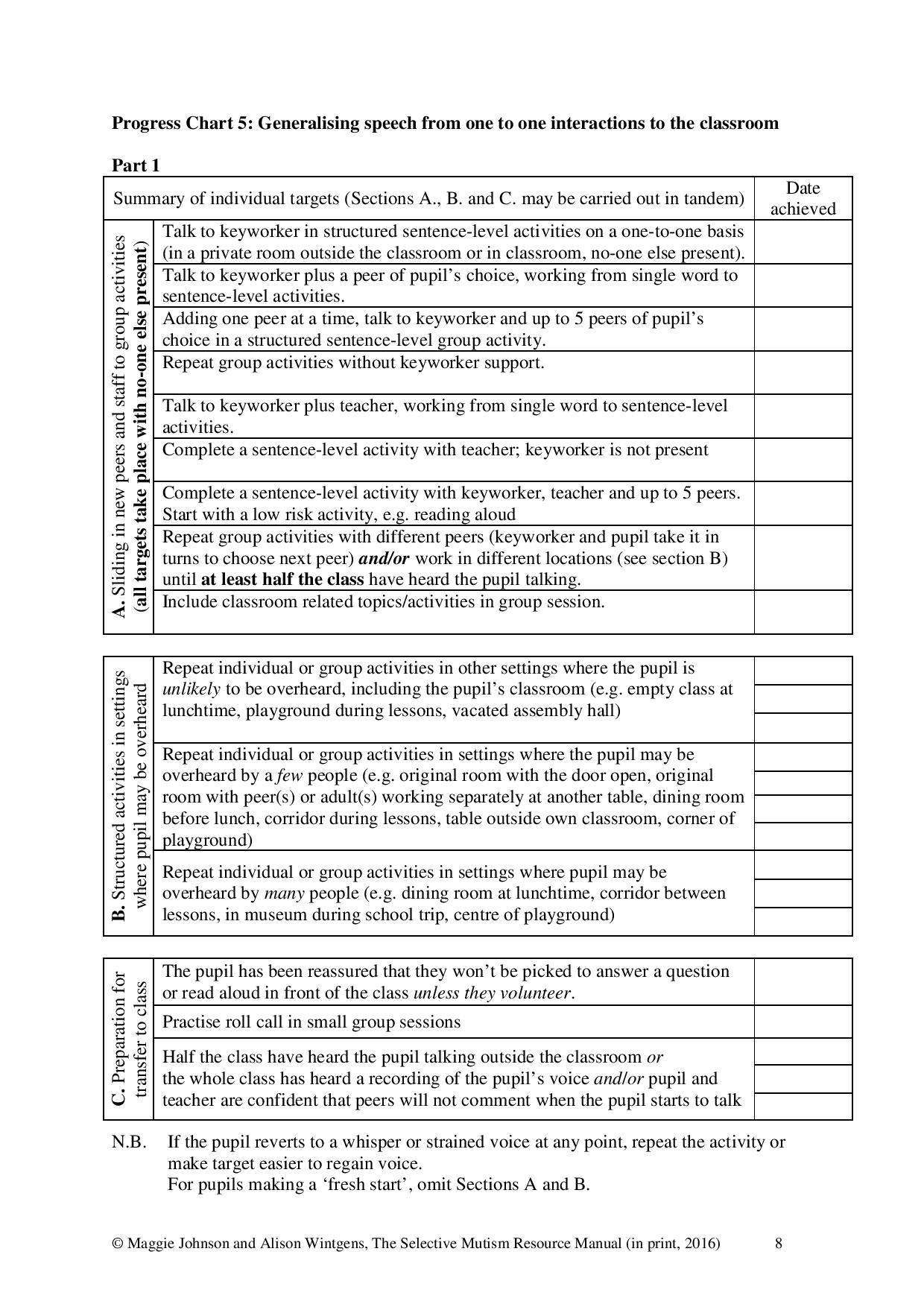

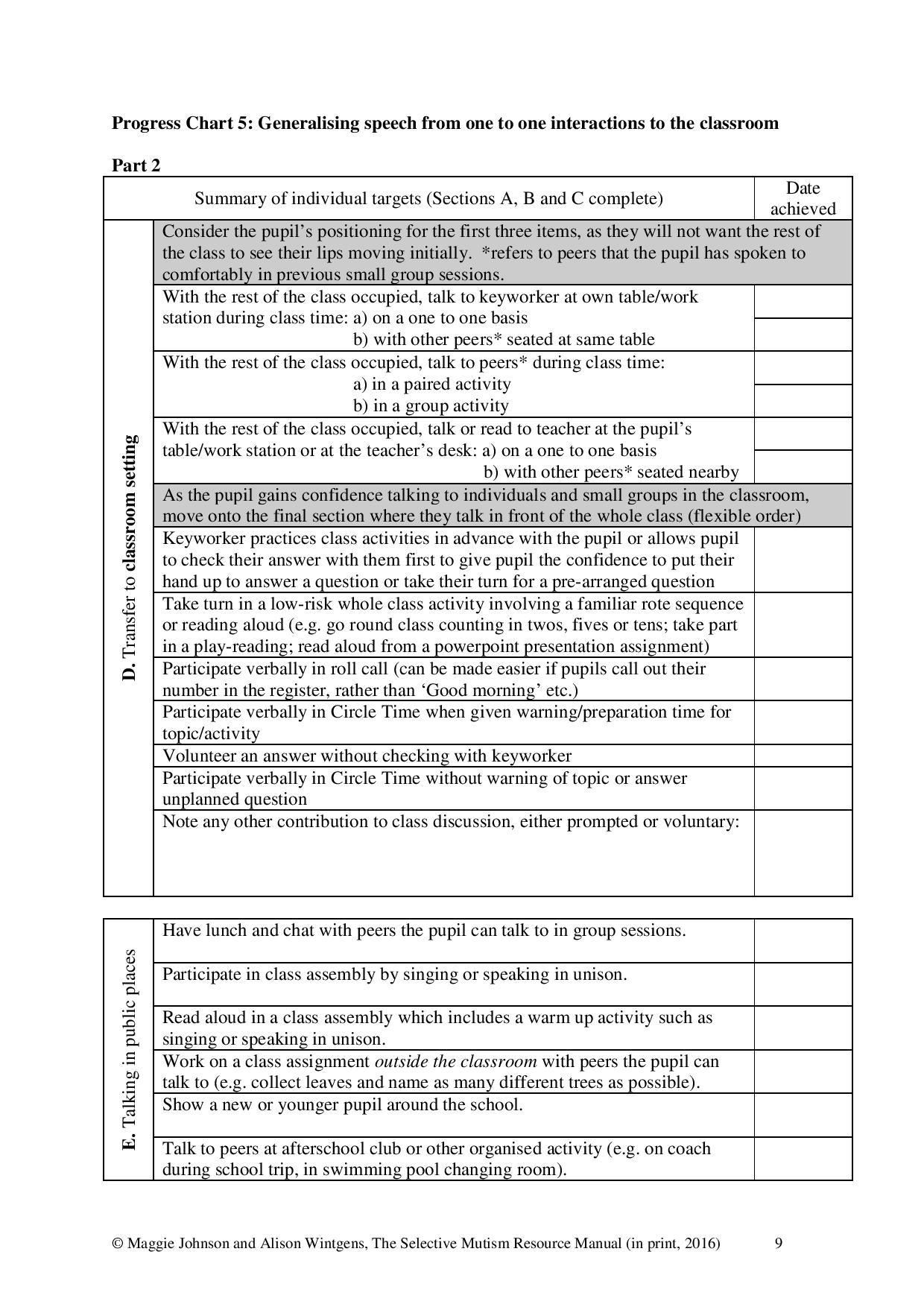

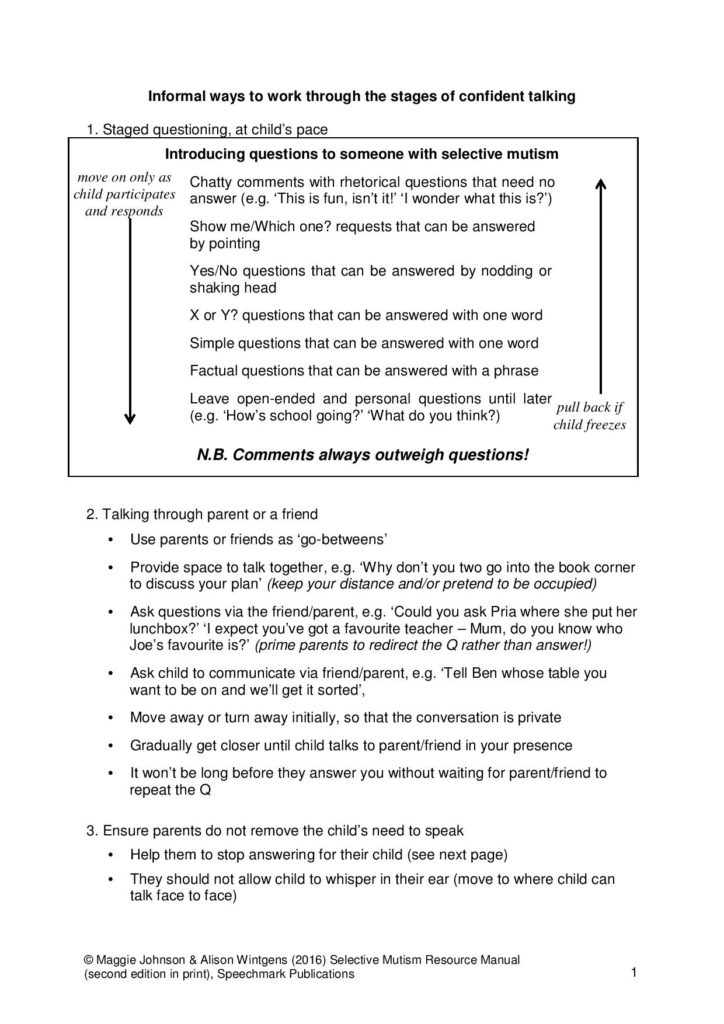

The Sliding-in Technique and Progress Charts

Informal Techniques

Older Children and Teens

The Older Child or Teen with Selective Mutism

Ricki Blau

Selective Mutism in the Older Child

Selective Mutism (SM) is usually noticed when a child begins pre-school or kindergarten, if not before. So when a student in the upper elementary or secondary grades has SM, it’s safe to assume that he or she has been living with Selective Mutism for many years. Within the lifetime of today’s teens, researchers and treating professionals have learned much about this anxiety condition. Young children who receive prompt and appropriate treatment now make great strides. But information about SM is still not as widely available as it should be—educators, doctors, and psychologists often fail to recognize SM or understand how to help affected children. Consequently, many children do not receive early diagnosis or appropriate support.

Older students with SM may have received no treatment or may have suffered years of inappropriate treatment and negative reinforcement. Instead of being helped to control their anxiety and become more comfortable at school, they may have been pressured to do the things they feared, such as speaking. Over the years they have developed ingrained behavior patterns and maladaptive coping mechanisms by which they avoid situations that make them anxious. Not speaking has become a habit that is difficult to break. They begin to see themselves as “the kid who doesn’t speak” as do many people around them. The fear of receiving attention if they should start to speak makes it harder to imagine changing. They may also have developed phobias about speaking or having their voice heard. Older children with SM often lag behind their age peers in social competence because they’ve had less experience with peers and adults. Treatment plans for the older child must take these complications into account. 1

Students with SM are, in general, extremely sensitive individuals. Older children and teens are acutely aware of their differences and the responses they elicit from their teachers and other adults. People have been trying to get them to talk for years! They understand that they repeatedly fail to meet standard expectations in the school setting. Consequently, they are wary and keenly aware of the most subtle pressure to communicate. Wanting to avoid attention, they typically have learned to hide the appearance of anxiety; while younger children may freeze and show a blank expression, older students more commonly appear relaxed and “ok,” even when they’re not.