Below is a range of leaflets suitable for use by parents and carers.

The documents below are in three sections:

SMIRA Leaflets

—

Advice to Parents and Carers during COVID 19

We at SMiRA – many of whom have family members who have SM ourselves – know that it is very hard to juggle all that is expected of us in terms of our own work, home schooling and so on. We can only do what we can do. So we want to say – if you can only focus on one thing with your SM youngsters during this lockdown period it would be to prevent them from withdrawing completely to the small comfort zone of home.

Returning to School After Lockdown:

Here is an additional document with regard to returning to school after lockdown:

Open Download

Where to Get Help with Selective Mutism

Registered Charity No. 1022673

The information charts below are particularly relevant for England and Wales (UK) but contain general points which may be useful elsewhere.

NB: Page 4 below contains a glossary of abbreviations

The links shown on the flowcharts are given in clickable form underneath each flowchart

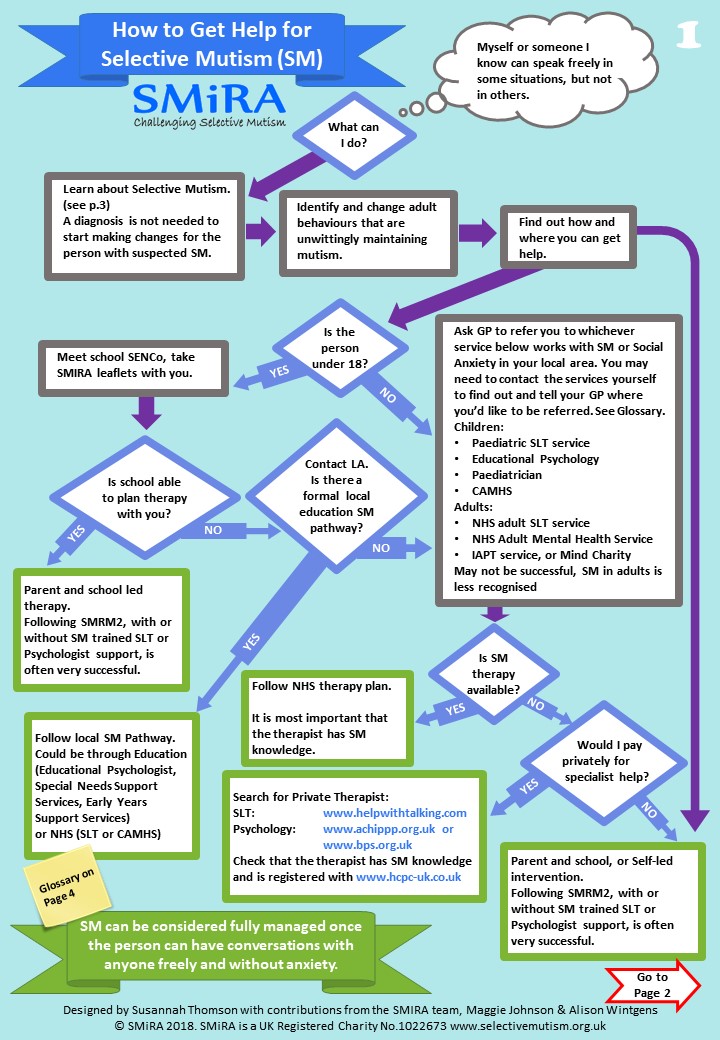

1. How to get help for Selective Mutism

Links given on page 1 above:

Search for Private Therapist

- Speech & Language Therapy: www.helpwithtalking.com – go to ‘advanced search’, tick the SM button and extend the distance it reports on as support can be done remotely for you

- Psychology: www.achippp.org.uk or www.bps.org.uk

Check that the therapist has SM knowledge and is registered with www.hcpc-uk.co.uk

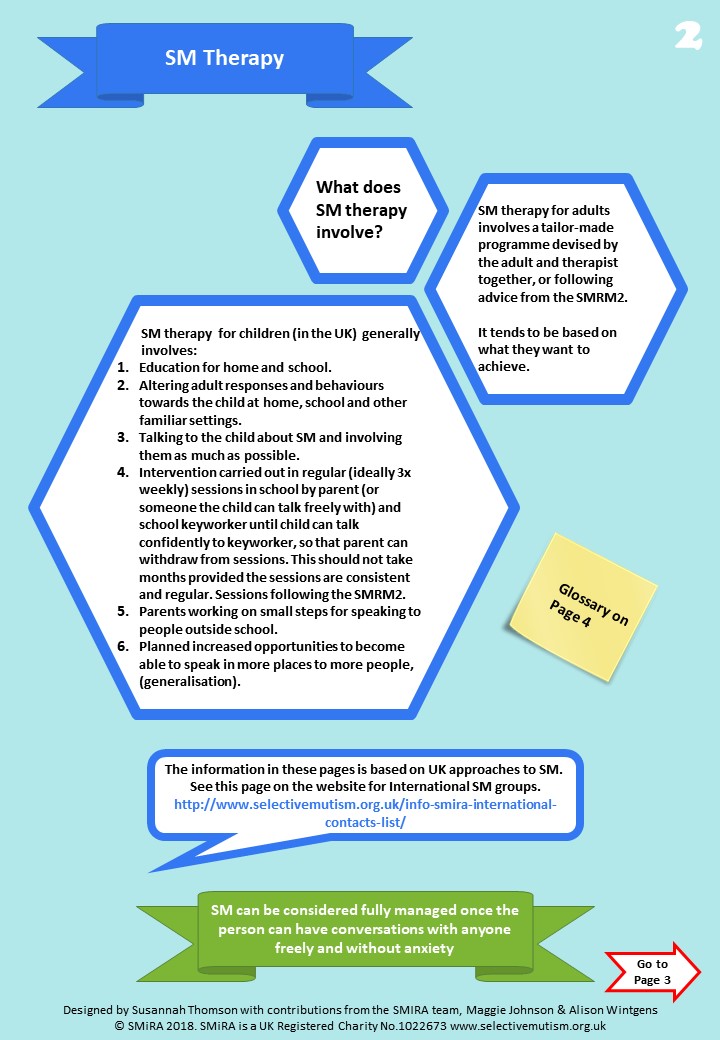

2. Selective Mutism Therapy

Links given on page 2 above:

SMIRA International Contacts List

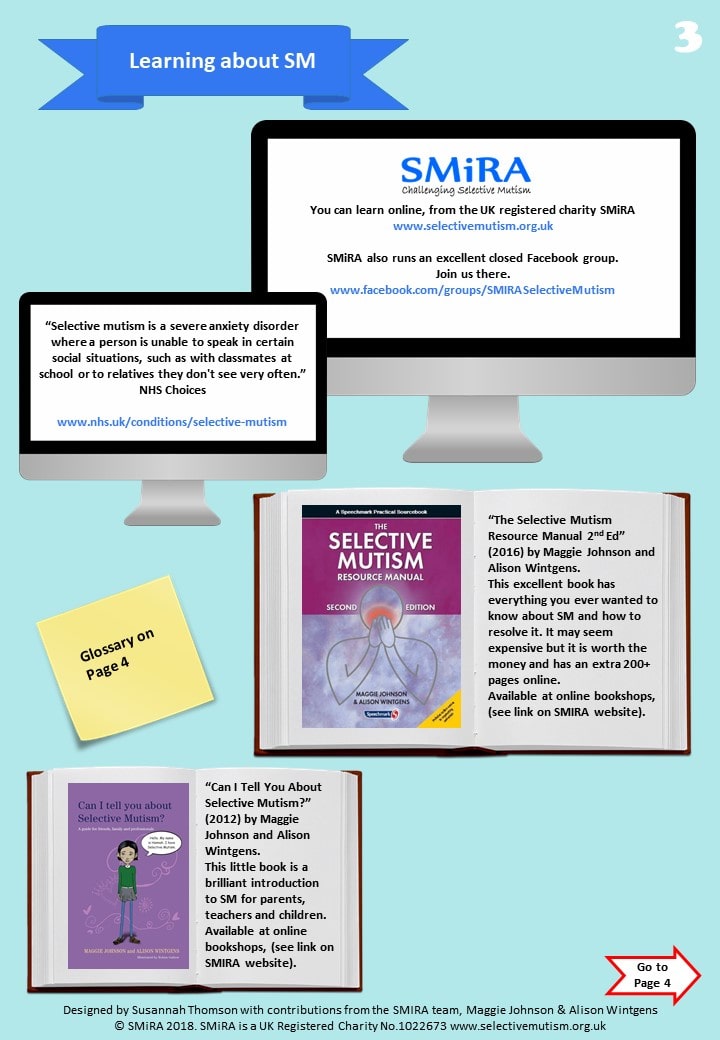

3. Learning About Selective Mutism

Links given on page 3 above:

- Learn online, from the Information section on this website

- Join the SMIRA Facebook Group (it’s a closed group so there may be a short wait while we approve your membership request.)

- See NHS Choices – Selective Mutism

Additional Reading

Details and purchase links for all of the books below are on the Books page on this website.

- “Selective Mutism Resource Manual 2nd Edition” (Johnson & Wintgens). Most changes in 2nd Edition are for older people with SM and generalising outside school

- “Tackling Selective Mutism” (Sluckin & Smith, ISBN-13: 978-1849053938, ISBN-10: 1849053936)

- “Can I tell you about Selective Mutism?” (Johnson & Wintgens, ISBN-13: 978-1849052894, ISBN10: 1849052891)

- “Can’t Talk? Want to Talk!” (Jo Levett, ISBN-10: 1909301310,ISBN-13: 978-1909301313)

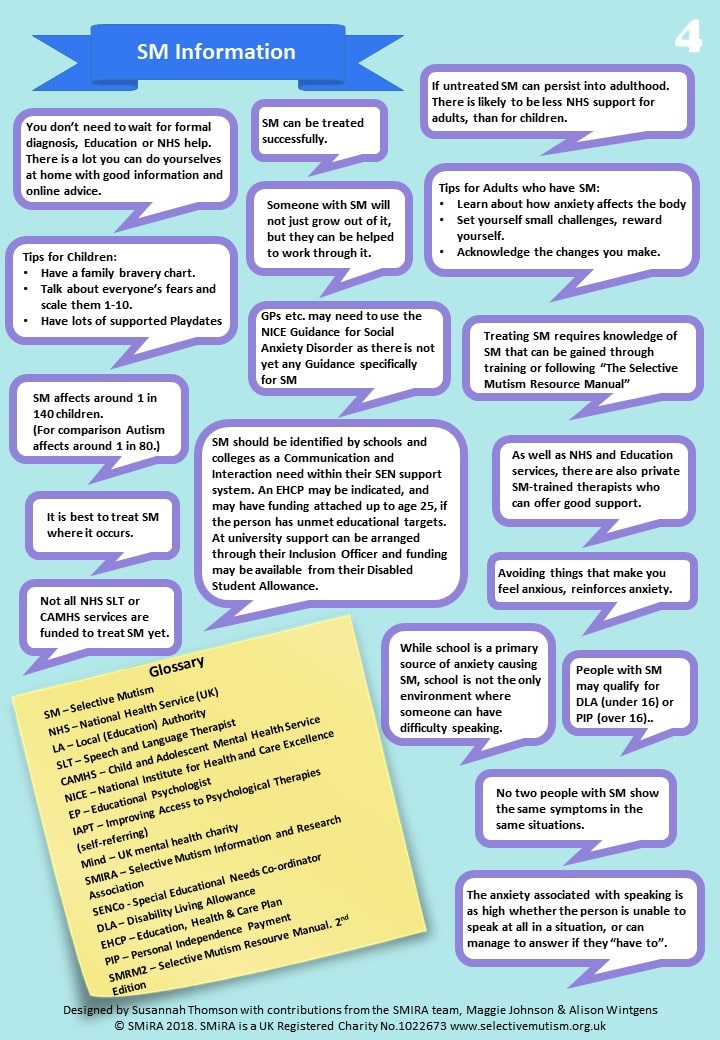

4. Selective Mutism Information

You may download these flowcharts to your computer as a PDF file, for emailing or printing out:

SMIRA Parents Leaflet

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

Your Selectively Mute Child

Help for parents from SMiRA

Selectively Mute children will speak in some situations, but be silent in others. This leaflet gives information about and strategies for dealing with the condition.

What is Selective Mutism?

Selective Mutism is a relatively rare anxiety disorder in which affected children speak fluently in some situations but remain silent in others. The condition is known to begin early in life and can be transitory, such as on starting school or on being admitted to hospital, but in rare cases it may persist and last right through a child’s school life.

These children usually do not talk to their teachers and may also be silent with their peers, although they do communicate non-verbally. Other combinations of non-speaking can also occur, affecting specific members of the child’s family. Often the child has no other identifiable problems and converses freely at home or with close friends. He/she usually makes age-appropriate progress at school in areas where speaking is not required.

Selective Mutism is rare, but there may be many children with the condition who are never reported, as they are not troublesome in school. For parents, having such a child can be very distressing, as they may feel blamed for the child’s mutism.

What causes Selective Mutism?

No single cause has been established, though emotional, psychological and social factors may influence its development. In the past these children were thought to be manipulative or angry, but recent research confirms an underlying anxiety, similar to ‘stage fright’. This may lead to other behaviours, such as limited eye contact and facial expression, physical rigidity, nervous fidgeting and withdrawal.

Is Selective Mutism associated with other disorders?

Selective Mutism may hide other educational or physical problems. If this is suspected, then a G.P. or Health Visitor should be consulted and referral to a Speech Therapist considered. They may ask about the child’s experiences and any delays in speech development, which may affect the child’s confidence in social situations. The child’s strengths and abilities in other areas should also be emphasised by the parents.

Can the Selectively Mute child be helped?

Yes, but early identification is important, so that some form of intervention can be planned.

The condition may not improve spontaneously and can become intractable. If the child is not speaking after a time of ‘settling in’, then the school’s Special Education Needs Co-ordinator (SENCO) should be consulted.

How can schools help?

All schools in England and Wales should follow the DfE’s Code of Practice for SEN and the Disability Rights Commission Code of Practice, to identify and monitor children with Special Educational Needs and/or disabilities. Initially, help is given within the school, but in later stages outside agencies like Educational Psychologists, Speech and Language Therapists can become involved. If the child’s difficulties are severe, then Formal Assessment may be undertaken. This may lead to an Education, Health and Care Plan, which would be reviewed annually.

The teachers may never have encountered a S.M. child before. Although anxious to help, they may feel threatened and frustrated. Understanding that S.M. is an anxiety response may ease these reactions. There are a number of strategies and treatment programmes available. Help and advice for professionals can be obtained from SMiRA.

How can parents help?

Acceptance, tolerance and understanding should be shown to the child, since anxiety can be infectious and may lead to overprotection. Patience and perseverance will be required for dealing with the condition.

The child should not be labelled as ‘non-speaking’ in front of other people or punished for remaining silent, as this will only increase anxiety, but should be praised for participating in social activities and for communicating verbally or non-verbally.

Conversation should be encouraged at home, and in other settings, about school activities, family events, thoughts and feelings, in order to develop verbal skills and confidence in selfexpression. Humour, jokes and laughter can teach the child that speaking is fun.

Talking and reading could be recorded at home, to allow the child to get used to hearing its own voice, and then played back at school with the child’s permission.

The S.M. child should be treated the same as other siblings and given the chance to speak or communicate non-verbally. Adults and other children should be discouraged from speaking for the child.

If the S.M. child cannot talk to some family members, then the condition should be explained to them, so as to avoid offence and enlist their co-operation. Use of the telephone may be one way to overcome this difficulty.

Some S.M. children seem particularly attached to pets. This interest could provide a motivation for speaking.

Imaginative play, dressing up and puppet play should be encouraged as S.M. children may speak when ‘in role’. Turn taking games will help with socialisation.

Non-verbal activities using the mouth, e.g. blowing bubbles, whistles, kazoos, tongue ‘clicking’, teeth chattering, drinking through long curly straws, can be fun and develop confidence.

When giving a party, it may help the S.M. child if only a few quiet children are invited. Too much social stimulation can be counter-productive and may increase the child’s anxiety.

The S.M. child should be encouraged to join leisure time organisations, even as a silent member initially, since this will help them learn necessary social skills.

Several home visits by the child’s teacher or teaching assistant can help to establish a different relationship.

If the S.M. child will speak to the parent on school premises, then a ‘situational fading’ programme could be used, with the teacher’s agreement. In this approach, the situation in which the child will speak is gradually adjusted, by changing the location and/or the people present, until the child speaks confidently.

A detailed and structured programme to help the S.M. child is given in “The Selective Mutism Resource Manual: 2nd edition” (2016) by Maggie Johnson and Alison Wintgens. (ISBN 978-190930-133-7)

If there are additional problems, then a child psychiatrist can recommend play or music therapy, which, in some places, is available under the NHS.

Children who have been S.M. for a long time often fear their classmate’s reactions if they should speak. Sometimes a change of class or school may lead to a breakthrough, but this should be carefully planned.

Photographs or a video of the school building and staff can give the S.M. child the chance to talk about them at home and practice verbal responses required in school.

Who can help the parents?

Having a S.M. child can be very stressful for parents, not least because the condition is so little understood. Early intervention is important in treating S.M. children, so concerns should be addressed seriously, although parents may need to be assertive.

Sources of sympathetic support are needed and are available. SMiRA maintains a website and Facebook group through which parents can contact and support each other. It has a DVD and books available for purchase. Parents can attend annual conferences held in Leicester, U.K..

Every Local Education Authority should provide an Independent Advice and Support Service for the parents of children with SEN and/or Disabilities.

IPSEA (Independent Panel for Special Educational Advice (0800 018 4016) may help you to identify your child’s educational entitlement and provide support if you are in disagreement with your L.E.A.

SMiRA is a support group for those affected by SM, parents and professionals. It was founded by Alice Sluckin, O.B.E., and is based in Leicester, U.K. For further details contact:

SMiRA Co-ordinator Lindsay Whittington on 0800 228 9765 E-mail: info@selectivemutism.org.uk

Website: www.selectivemutism.org.uk

What is SM? Leaflet for Primary School

Choosing a School

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

There are many factors to be taken into consideration in selecting a suitable school for your child. Amongst these may be the school’s geographical location in relation to your home, the ease of access, the presence of siblings or friends, the ethos or religious affiliations of the school, its reputation and results. The admissions policy of the Local Education Authority also needs to be followed.

Parents of a child with Special Educational Needs will be particularly concerned that the school should be able to provide support for their child.

All schools have an obligation to identify and make provision for children with Special Educational Needs. This requirement is enshrined both in law and the National Curriculum and should be detailed in the school’s S.E.N. Policy.

Each school should have one member of staff designated as S.E.N. Co-ordinator, (SENCo) who is likely to have specialist training in the subject, although amongst individual teachers, the knowledge and experience of children with S.E.N. may vary.

Each Local Authority should have some system of support for schools in assessing and meeting the needs of children with S.E.N.

Practical steps to be taken in choosing a school might include

- asking the Local Authority for information about their Admissions Policy and the location of schools in your area;

- asking other parents in your locality about their experience of the various schools in the neighbourhood;

- arranging to visit local schools with your child, to ‘get a feel’ of the school for yourselves;

- asking for a copy of the school’s S.E.N. Policy, which should be considered carefully, in addition to the usual School Prospectus;

- questioning the Headteacher about the number of children on the S.E.N. Register and the likelihood of special help for your child;

- checking the school’s OFSTED report for evidence on S.E.N. provision and support for individuals;

- comparing the school’s profile and numbers of children on the S.E.N. Register with those of other similar schools;

- comparing the school’s SATs results and Value Added scores with those of other similar schools, e.g. each LA publishes data on the Achievement of pupils with S.E.N. for every school and these are public documents.

No school is perfect, but they usually strive to do their best for the pupils in their care and are willing to work with parents in helping their children. If approached with respect, they are even willing to learn from parents about an unfamiliar condition like Selective Mutism.

© Denise Lanes, Shirley Landrock-White & SMIRA, 2007

www.selectivemutism.org.uk

Changing Schools Guidelines

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

Guidelines for Parents Who Contemplate Changing an SM Child’s School

SMIRA is asked from time to time whether a change of school might break the vicious circle of non-speaking. Here are some comments made by knowledgeable professionals that might be helpful.

- Before contemplating a change, it is desirable that the child should be in full agreement. If the child is well-settled and the teachers sympathetic, then a change may have an adverse effect.

- A change of school may be beneficial if the child already speaks outside the school situation, both with adults and children who do not go to the same school. This may indicate a decreased anxiety level, but the child may be currently afraid of how his/her peers in class will react should he/she start talking. This is a perfectly normal reaction as, like adults, children like to present a consistent picture of themselves to the outside world. Also, the child may feel it does not have the social skills to deal with the new situation.

- Once the parents and the SM child have agreed on a change of school, the new school must be taken into full confidence and with their help a gradual introduction should be planned. Meeting a member of staff, perhaps a class-room assistant, within home is likely to be very beneficial. The SM child should get to know at least one child attending the new school and preferably meet him/her at home for tea. Visits to the new school should be preferably when the building is empty. This could be combined with meeting the head and classroom teacher in as informal a situation as possible. Younger siblings, if available, should be taken. Good times for a transfer might be the end of term events, a Christmas Party or charity sale in the hall! It is inadvisable to rush a transfer, even if the child reassures parents that he/she feels very confident. Becoming a ‘talking person’ in class is likely to be a great event in the child’s life, requiring readjustment emotionally and involving responses of the sympathetic nervous system, which need time.

- If the transfer brings about the required result, i.e. the SM child is now talking in class, this should not be taken as a sign that the previous school had been at fault. On the contrary, it should be acknowledged that most of the groundwork had been done there and due to this the SM child is now ready for the next step, which is talking in class to peers and teachers. Perhaps this needs to be said as it would be a pity if the previous school, who might have taken a lot of trouble with a programme etc, were left to feel unappreciated.

WWW.SELECTIVEMUTISM.ORG.UK

©SMIRA 2006

Tips for Holidays

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

Tips for Holidays / Family Gatherings

The holidays can be a stressful time for anyone, but particularly stressful for a child with social anxiety or Selective Mutism. The unpredictability, new people and change in routine can sometimes be too much!

Here are some ideas that might make things go more smoothly for your holiday or family gatherings:

Prepare and over-prepare your child.

Show photographs of family/friends you might be seeing. Try making a “memory” or “matching game,” with duplicates and colour copies of photographs of each person – you could laminate them if you have facilities – and create a memory matching game. What a fun way to get to know family members you don’t see regularly but will be seeing! This might help ease some of the stress of meeting new people. You can even take them the photos along. It would make a great “nonverbal” interaction with someone at your gathering!

Find out where you’re going for the gathering. If it is close by, try to go to that person’s house a few days before the event so your child can “check it out” and at least be familiar with the setting.

Talk about where you’ll be going. Even “study” that area. If you’re travelling away from home, show your child where you are going on the map. Help him find some interesting facts on the area you’ll be visiting. Sometimes taking the focus off the trip details and making it fun and an “adventure” can decrease anxiety.

For children who get stressed by change in routine as much as new people and places, draw stick figure cartoons covering each day of the holidays and go over the pictures several times explaining what will happen (when/where/how long etc.) like an exciting story that’s about to unfold. This ensures that children aren’t overwhelmed by words, and gives them the security of something visual to refer back to as often as they like.

Prepare friends and family members

It is important to tell others how to relate to your child. Usually when this is explained and people understand that your child has a form of social anxiety, people are more willing to accommodate your child. SMIRA’s leaflet ‘What Selective Mutism Means’ can be useful in these circumstances and is available to print off from the website. Business-sized cards containing information are available to purchase – please ask for information.

Let your child be your gauge

Allow time for warm-up. Sometimes this takes a lot longer for SM children than others. It may even be 45 minutes to an hour. Be patient and if you have to sit in the room with the other children to help him or her get used to things, usually that pays off and he or she becomes comfortable more quickly. Don’t do everything for them or always talk for them, but having a “safe haven” can be comforting for them and helps them progress more quickly. Or it may not! If your child is obviously uncomfortable, find a quiet spot where he or she can do something calming. If that outgoing relative keeps coming up for kisses and hugs, take charge and speak up for your child! It doesn’t have to be made into a big deal, but if your child is struggling, it will probably affect the whole situation and make the event less pleasurable, and of course, make things more stressful on you!

Don’t be afraid to speak up for your child. You don’t need to say “He’s shy” but maybe “He’s not in the mood for hugs right now” or “She’s had all the kisses she needs today!” It’s okay to use humour or be silly, but no need to negatively reinforce something that isn’t your child’s fault! It also might help to let your child bring something familiar like a toy, book or game to have a “little piece of home” away from home.

Be realistic

Be realistic in your scheduling around the holidays. Children with Selective Mutism also often have sensory issues and get overwhelmed easily. Add a new setting, different schedule, new people and foods, and you’ve got the formula for a guaranteed meltdown! Be wary of trying to fit too much into the day and try to maintain routine as much as possible. You might run into friends and family who just “don’t get it.” Sometimes it is necessary to limit time spent around those people until you are further along in your child’s treatment or until they are more willing to understand what you and your child are going through. It’s also okay to say “no.” If things get overwhelming, cut back on commitments or create new traditions that maintain the peace for all involved.

Take care of “you”

Make sure you include time for yourself. Being the carer to a child with additional needs is stressful year-round. The ups and downs associated with SM can be enough to put you over the edge! Find something you enjoy doing and try to fit in it each day or at least every other day. Also try to include family time or down time for you and your children. This is valuable time to just have fun and, if you’re lucky, sometimes that is when they open up!

The holidays can be a stressful time. When raising a child with Selective Mutism, sometimes you have to be the one to “take charge” and set limits in order for the holidays to be enjoyable for you and your family.

Adapted for the UK from an article written by Gretchen Aerni for SMG-CAN Quarterly Newsletter,

November 2006

Summer Holidays – ways to continue progress

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

Summer Holidays – ways to continue progress

Written by Gail Kervatt M.Ed for the USA-based group SMG-CAN and reproduced here with her kind permission

Summer break conjures up thoughts of lots of “fun”. To most families summer break means fun at the beach and the pool, fun having barbeques with friends, fun visiting Grandma and Grandpa, fun on that special vacation, fun playing with siblings and neighbourhood friends, fun sleeping late!

However, for a selectively mute child, summer break also means a “break” in the school intervention to help the child overcome the anxiety induced mutism. It means a two month break in routine, a two month break in provided services, a two month break in socializing with the teacher and classroom peers within the school setting. The summer break often can result in a regression in progress, in the lowered anxiety in the school setting and in the coping skills that have been practiced during the school year .

Parents can prepare and take some steps early to make sure that progress continues in September from the point where the child left off in June. Here are some suggestions:

- Meet with your school principal in sufficient time to discuss placement for next year. Discuss teacher choice and children with whom your child relates. This is very important and you may have to insist upon your request being granted. You may want to meet with the new teacher and discuss their knowledge, strategies and feelings of having your child in their classroom.

- Once the placement is made, find ways to slowly introduce and acclimatise your child to next year’s teacher. This can be accomplished through the “key worker” who works with your child in a small group and through the classroom teacher. The “key worker” in the school can invite possible teacher choices, one at a time, to the small group setting to play a game with the group. The classroom teacher can invite possible teacher choices into the classroom to participate in group activities and/or reading groups. The classroom teacher can send your child with a friend to deliver notes to the possible teachers.

- Spend some time with your child and a new classmate on the playground and then in the new classroom where he/she will be placed. This can be done after school and during the summer. Ask your child to choose the desk where he/she would like to sit.

- Ask the new teacher to make an effort to communicate with your child during the summer. This can be accomplished with a welcoming note or postcard, a phone message and/or a visit to your home. Take your child to school during August to help the new teacher set up the classroom. There should be no pressure for your child to speak during these encounters.

- As soon as possible, get a list of the new class and arrange play dates often with children of your child’s choice. This way your child will enter the new classroom in September knowing there will be a friend or two there with him.

- During the summer break provide opportunities for your child to practice communicating in the “real world” such as at a restaurant, the snack bar at the park, the library or a store. Even if your child can only point to a menu choice or item in a store, continue to expose him/her to these situations. Also, it’s important to model appropriate social interactions for your child. You might want to read Angela McHolm’s book, Helping Your Child with Selective Mutism, which demonstrates how to set up a “communication ladder” and go from there.

Enjoy that summer break, a wonderful time to relax and be together doing fun activities, but continue to help your child to ‘rid the silence’.

Phonics Testing

Below is a link to a pdf document regarding Year 1 Phonics Test from The Communication Trust:

“Communicating Phonics – A guide to support teachers delivering and interpreting the phonics screening check for children with speech, language and communication needs”

Pages 55-59 are the ones relevant for SM.

Leaflets from the Selective Mutism Resource Manual (2nd Edition)

—

Video chat – small steps

We are posting this link to Maggie Johnson’s resource at the top as it is especially relevant for online therapy at the moment:

Supporting Children with Selective Mutism – Advice for Parents

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

1. Ensure that your child feels valued and secure

Children with selective mutism are so anxious about talking that the muscles they need for speaking freeze (especially their vocal cords) and they cannot make a sound. Any anxiety, disapproval or uncertainty they pick up from adults will increase their own sense of guilt, failure and fear about the future – they’ll then tense up and find it even harder to speak.

It’s not just teasing that makes children feel bad about themselves. Asking ‘Why don’t you talk?’ or ‘When will you have a go?’ implies that you don’t like them the way they are, wish they were different and worst of all, have no idea what to do about it. They will worry that they are upsetting you and try to avoid situations that are likely to highlight their difficulty. Repeatedly asking ‘Did you talk today?’ or ‘How did you get on?’ makes children dread going to school in case they let you down.

We need to tell children why they find it hard to speak at certain times rather than ask questions they cannot answer. Reassure them that everyone grows up with childhood fears and although they find talking difficult right now, they’ll find it gets easier as they get older. Their fear will go away because they will get used to talking, one tiny step at a time, and meanwhile there are lots of other ways to join in and have fun. Your child needs approval whether they speak or not, so be positive about their efforts and tell them how brave they are when they try new things. The calmer you are, the more relaxed your child will be and the quicker they’ll improve.

2. Try to reduce embarrassment or anger about your child’s behaviour

We have to accept our children as they are and not put them on the spot by pushing them to talk to other people or drawing attention to their speech. Allow them to warm up in their own time, help them to loosen up through physical play, join in activities yourself or give them a job to do which you know they will do well, and they are much more likely to relax sufficiently for their speech muscles to start moving again.

3. Educate family and friends about the nature of your child’s difficulties

This should be no different to telling other people that your child has a real fear of water or dogs and expecting them to make allowances. Never let your child hear you tell people that they can’t or won’t speak, as this reinforces their belief that talking is impossible and can make it very difficult for them to break the pattern – especially when you are present! Your message needs to be much more positive. Explain that when they are worried about talking they can’t get their words out, and that asking questions and putting pressure on just makes it worse. They will be able to speak once they conquer their fears and when they do, it’s important that no fuss is made – everyone needs to carry on as if they’ve always spoken! Meanwhile, help others respect alternative forms of communication – nodding, pointing, smiling, waving, writing, talking through a friend or parent etc.

eg:

- Joe needs a little while to warm up, please don’t think he’s being rude.

- Amy will be full of this when she gets home but don’t worry if she doesn’t talk straightaway. She needs to watch and listen first

- Sam’s having a great time and if we just let him join in at his own pace he’ll be able to start talking.

- Jade would love to play with you. She can show you what her dolls like to do and later she might tell you about them too.

- Sarah’s going to listen while we have a chat. She’ll interrupt or text me if she wants to add anything.

- When Gemma is used to everyone she’ll talk as much here as she does at home!

- Can you please make sure no-one makes a big fuss when Dale starts talking? If you just talk back quietly he’ll find it easy to carry on.

- Ali is getting much braver about talking to grown-ups but to start with it would really help him if you could let him tell his friends what he wants to say.

4. Build confidence by focusing on your child’s achievements

In conversations with your child, your friends and yourself, focus on what your child CAN do, not on what they CAN’T. Support them in their interests and creative talents and find ways in which they can comfortably demonstrate their skills to others.

5. Keep busy and have a routine

Activity and physical exercise are good for mind, body and soul and help to keep anxiety at bay. Sitting around doing nothing increases stress, as does uncertainty about the day’s events. Start each day with a plan that includes exercise – whether this is letting off steam after school for younger children, sweeping up leaves or walking the dog for older children.

6. Remember that avoidance strengthens fear

When we do things for our children or let them avoid activities, we are confirming the child’s belief that these things are too difficult or threatening for them. Of course we do not want our children to fail or become distressed, but by removing the need to engage at some level, we are taking away their opportunities to learn, experience success and become independent. The secret is to make activities easier, shorter or more manageable so that children are less overwhelmed and have a go. In this way, we show that anxiety is a normal part of life and can be managed. If their only way to deal with anxiety is to eliminate it completely through avoidance, they will grow up with no coping strategies.

eg:

- Instead of ordering for your child, ask them to show the waiter what they want.

- Instead of avoiding a party completely, arrange to arrive first when it’s quiet and only stay 15 minutes – chances are your child will ask to stay a bit longer!

- Instead of taking something that is offered to your child, first reassure your child that it’s OK to take it and if necessary, ask for it to be put somewhere handy so your child can take it when they are ready.

- Instead of turning down an invitation, ask if you can go too as a helper.

- Before children opt out of an activity completely, try to work out with them which part they find difficult/distressing and look for a solution.

- If children miss school, do not let avoidance become a fun option. Make sure they stay in bed or do schoolwork during school hours rather than play. Discuss any concerns and enlist the school’s support to ensure a positive return.

- Rather than answer for your child (which quickly becomes a habit!), try one of the following:

- repeat the question so that your child can look at and answer you

- rephrase it as a ‘Yes/No’ question so a nod or shake of the head will do

- deflect it, e.g. ‘I’lI ask Peter that in a moment once he’s settled in’ or ‘That’s a good question – Peter, do you want to have a little think about that and tell me later?’

7. Accompany child but as a general helper rather than their personal assistant

If the only way your child will attend a school trip, Brownies, football etc. is if you go with them, volunteer yourself as a general helper, make a point of talking to other children and get actively involved to assist socialisation rather than dependency.

8. Let children know what is happening

Warn children of changes to their routine and prepare them for new events by talking through what will happen. Rehearse or make a game of real-life scenarios such as going to the doctors, opticians, McDonalds or ordering a Chinese takeaway. Take it in turns to be the patient, doctor, server, etc. and practice/write down phone calls. Visit new schools as soon as possible to meet and educate key staff, take photos to show relatives, throw wet sponges at the summer fair etc.

9. Provide an escape route

Feared situations are a lot easier to tolerate when we have the control of knowing we can opt out if it all gets too much – the signal to the dentist, the rescue text, independent means of transport.. Children have far less control over their escape routes than adults so it’s important to give them the same security. If children are anxious about a school trip or going to a friend’s house for example, arrange to pick them up at lunchtime so they only go for half the day or say you will phone at intervals to see if they need collecting. Gradually extend the time.

10. Don’t spring surprises on your child

Many parents don’t like to warn their children about a forthcoming event because then they see their child worrying for days or weeks and doing all they can to avoid it. They prefer to tell their child on the day and find they cope reasonably well because they haven’t had time to think about it.

This is a risky strategy that increases rather than reduces anxiety. On the surface it works well but it’s a very short term gain. Even when children cope reasonably well with the event that was sprung on them, they will usually have tolerated it in a high state of tension rather than feeling relaxed and in control. In the long term, they are constantly on the alert, waiting for the next surprise, and doubt sets in that they can trust anything to be what it seems. Furthermore, they are being deprived of the opportunity to learn that anxiety doesn’t have to be eliminated, it can be managed through preparation and coping strategies such as educating key people and having an escape route.

11. Remember that it can be just as scary talking to children as adults

Help your child play with other children rather than leaving them to get on with it. Join in with them, starting with activities or games where talking is optional, so you can all concentrate on having fun.

12. Establish safe boundaries with your child so they can take small steps forward

Laughing, singing, talking in unison and talking to parents will be a lot easier than talking to other people. But children are often afraid to do these things in case it draws attention to them and leads to an expectation to speak. Reassure your child:

eg:

- Grandma knows you can’t talk to her just yet, but it’s OK to talk to me and Daddy in front of her.

- It’s hard to talk to your teacher at the moment but it’s OK to laugh.

- It’s OK to join in the singing, no-one will make you talk afterwards.

- It’s fine to talk to us here in a very quiet voice, no-one will make a fuss. You don’t need to speak on your own, you can just try joining in when everyone speaks together.

13. Use telephone and recording devices as a stepping-stone to the real thing

Go to www.talkingproducts.co.uk for lovely ideas for presents and talking practice – children can personalise greetings cards with a recorded message or make a talking photo album for example. If children cannot speak to their relatives or teacher face to face yet, they could leave a message on a mobile phone or have a conversation via a ‘Talking Pod’ or MP3 player. How about encouraging siblings to take it in turns to record the message on your home answerphone? Teachers can listen to children reading to their parents over the phone rather than in the classroom. Finally, children can get used to talking to strangers by practising with voice recognition software (e.g. Train Tracker 0871 200 4950). This builds up confidence, volume and the ability to repeat without panicking, safe in the knowledge that it’s a robot, not a real person. Before you know it they’re ordering a Chinese or pizza over the phone!

14. Push the boundaries, starting with safe strangers

Do not be afraid to let children go without every now and then so they develop that bit of extra determination to confront and overcome their fears. They’ll often surprise you! e.g. Explain you are too busy to stop what you are doing but there is the money if they want to get an ice-cream. Do not get it for them. If the ice-cream van drives away, calmly say, ‘Never mind, you can try again tomorrow’. Reassure children that only a couple of words are needed and there will be no need to have a conversation.

15. Encourage a very quiet voice rather than whispering

Accept whispering on the odd occasion if you can genuinely hear and are in a hurry but do not lower your head so that your child can whisper in your ear. This easily becomes a habit and encourages avoidance. A very quiet voice is much better than a whisper as it will gradually get louder as your child gains confidence.

So, if your child wants to talk to you but is worried about being overheard, either:

a) turn so that you are blocking your child’s view of whoever they are concerned about and, maintaining eye-contact, quietly say ‘Pardon?’ (do not whisper!) or ‘it’s OK, X isn’t listening’. or

b) move far enough away from onlookers so that your child can speak to you face to face rather than in your ear. If you are in the middle of a conversation, ask your child to wait for you to finish and then pull away to speak to your child.

There is no need to explain what you are doing but if your child asks why they can’t whisper, explain that too much whispering will give them a sore throat so it’s better to stand where they can talk normally. Stick to this and very soon your child won’t need to move so far away. N.B. This technique only works for parents and people with whom the child has no difficulty talking when there’s no-one else around.

16. Ask friends, relatives, shop-assistants etc to speak to your child through you if you know they will not be able to respond directly.

eg:

‘What colour would your son like to try on first?’

‘Max, what colour would you like to try on first?’

(Max points to brown shoes) ‘He’d like to try on the brown ones please.’

‘I love Max’s blazer. Could you ask him what school he goes to?’ ‘Max – you like your school don’t you, what’s it called?’

‘St. Joseph’s’

‘Max says it’s called St. Joseph’s.’

If children are relaxed with you in public and know you are not pushing them to talk directly to other people, you will find that they begin to cut out the middle man!

17. Help your child offload their stress safely

Being watchful, anxious and unable to speak for much of the day is a great strain. It’s common and can be challenging for the whole family to get the brunt of SM children’s pent up emotions when they come home from school, but they need you to understand that it is natural to feel this way and to provide a calm, safe place rather than more emotional upheaval. Your child may need a chance to relax completely after school before attempting homework, or a physical outlet for their frustration – trampolining, swing-ball or swimming for example. Violent computer games are NOT a good idea!

When upset, your teenage child may use a flat tone of voice which sounds rude and confrontational. Do not rise to this or you will escalate your child’s stress and make things even worse. Recognise their anxiety, take a deep breath and continue in a calm gentle tone. If they lash out verbally or physically, calmly reflect, ‘I’m sorry you’ve had such a bad day’ and leave them on their own to listen to music, bash a pillow or put it on paper until they feel better. When things are calmer, acknowledge their frustration but explain that the family do not have to suffer their outbursts so will keep out of their way if they try to take it out on other people. Discuss alternative outlets and say that if you know what has upset them there may be something you can do to help.

Finally, look at your own lifestyle. Does your child have good reason to be concerned about your behaviour? They cannot improve while worrying about you.

18. Show your child it is OK to relax and have fun

If parents have unrealistic standards and try to keep their children and house spotless with everything in its place, their children will constantly worry about spilling or breaking something, getting food on their hands or faces, touching something unhygienic or making the room untidy. They will get extremely anxious at school or other people’s houses where they perceive a different set of standards. They will not be able to tolerate lively, unstructured behaviour or engage in normal messy play like finger-painting, papier mâché or digging for worms.

This fear of getting dirty and putting something in the wrong place can spread to a fear of using toilets outside the home and inability to take risks. It will certainly impact on children’s ability to relax around other people and make friends. It is important for all the family to enjoy mealtimes, gardening, cooking and play without fear of making a mess – put away the wet-wipes til the end of the activity!

19. If different languages are spoken at school and home, set a good example

Your child needs to hear you having a go at speaking the school language at school and with their new classmates. Show them learning is fun and mistakes are OK! Ask the teacher if your child can spend some time with other children who speak the same language for part of the day, teaching their vocabulary to English speaking children so everyone sees what it is like to learn something new.

20. Make explanations, instructions and reminders visual

Anxious children quickly feel overloaded, forget things easily and tend to take things literally or at face-value. Anxiety causes ‘brain-freeze’ so we are unable to take in all we hear and cannot think laterally or rationally. Put things on paper so that children have a checklist to follow rather than trying to remember instructions. If they repeatedly ask the same question for reassurance give them a visual reminder and respond to further questions by asking them to refer to it and tell you the answer.

21. Acknowledge anxiety but do not fuel it with an emotional reaction; calmly provide a diversion or clear plan of action

Children need brief sympathy followed by matter of fact guidance and strength – not anger, worried looks or protective cuddles which just confirm that there is something to be afraid of. For example, if they complain of a tummy-ache before visiting a friend’s house say ‘Poor you, I know you’re a bit worried but Josh’s Mummy knows all about waiting until you’re ready to talk. I know what will help until our taxi gets here, where’s that catalogue you wanted to look at?’

Or, if they don’t want to go to the doctor’s say ‘We can take something with us to play in the waiting room. Let’s choose something and have a game now’.

If they have difficulty separating from you, stay but do not cling to them or put them on your lap – explore the room together and find things to do. If appropriate, explain how you or others are going to make situations manageable for your child.

Older children will need to discuss their fears about starting a new school, changing class, going on a school trip etc. Externalise their anxieties by breaking the events down and writing each component on a post-it note – the coach-journey, taking the right clothes, getting to the toilet in time etc. Then sort the post-it notes into 3 columns – things I don’t have to worry about, things that worry me a bit and things that worry me a lot. Now you can agree on which part to tackle first and strategies to help. Some post-it notes you will leave to deal with another time but already the anxiety will be out of the child’s head and seem more manageable. Unless problems are broken down in this way, children will want to avoid situations completely without understanding the specific source of their anxiety.

22. Answer anxiety questions with another question so that your child becomes the problem solver

Children tend to bombard parents with questions as they try to control their anxiety,

e.g. Who’s going to be there?

How long will it last?

Have they gone?

Are you going to talk to my teacher? etc. etc.

Instead of answering (which rarely alleviates the anxiety) respond with another question so that children start to understand their anxiety, and can think about coping strategies:

e.g. Who do you hope will be there?

How long do you think you can manage?

Why do you want them to go?

If I talk to your teacher, what would you like me to say?

23. Celebrate your child’s unique qualities

We cannot change the personality of SM children – and wouldn’t want to! They are naturally sensitive individuals who take life seriously and set themselves impossibly high standards. The downside is a tendency to be overwhelmed by novelty, change and criticism; the upside is an empathetic, loyal and conscientious nature. When treated fairly and allowed to show their true colours, SM students often display far more creativity and insight than their peers.

Maggie Johnson

Selective Mutism Advisory Service, Kent Community Health NHS Trust

Do I answer if someone asks my child a question?

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

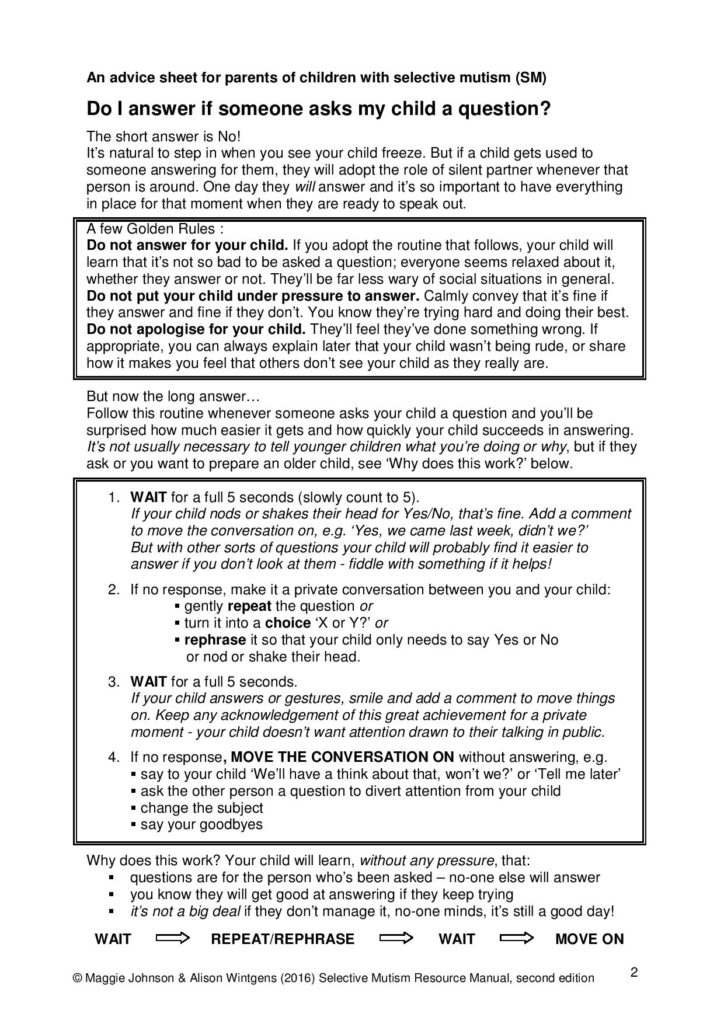

HANDOUT 11 : An advice sheet for parents of children with selective mutism

Do I answer if someone asks my child a question?

The short answer is No!

It’s natural to step in when you see your child freeze. But if a child gets used to someone answering for them, they will adopt the role of silent partner whenever that person is around. One day they will answer and it’s so important to have everything in place for that moment when they are ready to speak out.

A few Golden Rules :

Do not answer for your child. If you adopt the routine that follows, your child will learn that it’s not so bad to be asked a question; everyone seems relaxed about it, whether they answer or not. They’ll be far less wary of social situations in general.

Do not put your child under pressure to answer. Calmly convey that it’s fine if they answer and fine if they don’t. You know they’re trying hard and doing their best.

Do not apologise for your child. They’ll feel they’ve done something wrong. If appropriate you can always explain later that your child wasn’t being rude, or share how it makes you feel that others don’t see your child as they really are.

But now the long answer…

Follow this routine whenever someone asks your child a question, and you’ll be surprised how much easier it gets and how quickly your child succeeds in answering. It’s not usually necessary to tell younger children what you’re doing or why, but if they ask or you want to prepare an older child, see ‘Why does this work?’ below.

1. WAIT for a full 5 seconds (slowly count to 5).

If your child nods or shakes their head for Yes/No, that’s fine. Add a comment to move the conversation on, e.g. ‘Yes, we came last week, didn’t we?’ But with other sorts of questions your child will probably find it easier to answer if you don’t look at them – fiddle with something if it helps!

2. If no response, make it a private conversation between you and your child:

- gently repeat the question or

- turn it into a choice ‘X or Y?’ or

- rephrase it so that your child only needs to say Yes or No or nod or shake their head.

3. WAIT for a full 5 seconds.

If your child answers or gestures, smile and add a comment to move things on. Keep any acknowledgement of this great achievement for a private moment – your child doesn’t want attention drawn to their talking in public.

4. If no response, MOVE THE CONVERSATION ON without answering, e.g.

- say to your child ‘We’ll have a think about that, won’t we?’ or ‘Tell me later’

- ask the other person a question to divert attention from your child

- change the subject

- say your goodbyes

Why does this work? Your child will learn, without any pressure, that:

- questions are for the person who’s been asked – no-one else will answer

- you know they will get good at answering if they keep trying

- it’s not a big deal if they don’t manage it, no-one minds, it’s still a good day!

WAIT >>> REPEAT/REPHRASE >>> WAIT >>> MOVE ON

© Maggie Johnson and Alison Wintgens

Do’s and Don’ts at Pre and Primary School

Do’s and Don’ts at Secondary School

Easing in Friends and Relatives

An advice sheet for parents of children with selective mutism

Easing in Friends and Relatives

An Informal Approach to Building Rapport and Facilitating Speech:

Do you have a family friend or relative that your child sees on a fairly regular basis but is unable to speak to? Try these six steps at home over several sessions or over the course of a few hours.

C = Child P = Parent F = Familiar adult

Whenever C speaks, P and F must not draw attention to this fact, but calmly respond to what C says as if they’ve always spoken.

1. EDUCATION

Make sure F understands the nature of selective mutism and accepts that it is a phobia which needs sympathetic support to overcome. You need to agree:

- C is not being rude, difficult or silly. Their silence is caused by anxiety like stage-fright, so no-one must take it personally.

- No-one will put pressure on C to talk – no bribery, persuasion, negative comments or expectation to say ‘hello’, ‘please’, ‘thank you’ etc.

- It will help C talk in F’s presence if F initially avoids watching C while C is speaking or trying to speak.

2. REASSURANCE

Before F arrives, tell C that F does not expect C to talk to them unless they want to. They just want to have a nice time chatting to P and possibly joining in whatever C is doing or wants to show them. Set C up with a practical activity they enjoy. Tell C they can chat to you as normal and F will not butt in or make any comments about them talking. Remind them that if they want to be brave and have a go at talking to F that’s fine, but it’s up to them and F won’t be upset if they don’t.

3. BEING COMFORTABLE IN THE SAME SPACE

The first target is for C to feel comfortable around F so stick with this stage until C appears fairly relaxed and is moving and smiling easily:

- F greets C but does not ask any questions. F can make positive comments about C (e.g. admiring a picture they’ve drawn) but initially their focus should be on light-hearted chat with P.

- P should also give F more attention than C initially, to let C physically relax in the same room at their own pace. At this point young children will very often dip in and out of the room, as if they are testing the water.

- P includes C by making casual comments that don’t require an answer,

e.g. “We had a great time at the zoo, didn’t we?”, and distracts C with physical activity such as handing out biscuits, drawing a picture, finding their model collection, decorating cupcakes etc. - P can ease C in gently by asking C ‘Yes/No’ questions which C can answer non-verbally by nodding or shaking their head. However…

If C uses gesture to try to tell P something (e.g. points at the biscuit tin) P must not interpret this or try to guess what C means. Such behaviour delays progress by showing C that gesture is a successful and acceptable form of communication. P can say, “Sorry, I’m not sure what you mean” or ask C an ‘X or Y?’ question, e.g. “Are you asking for a biscuit or do you want to offer F a biscuit?” WAIT for an answer (at least 5 seconds) and if no response, P smiles and says, “it’s OK, you can tell me in a little while”, and carries on talking to F.

4a. TALKING TO PARENT

Once relaxed, the next target is for C to talk to P face to face in F’s presence (whispering in P’s ear is not an option!):

- P starts to ask C questions that cannot be answered Yes or No, so C can no longer just nod or shake their head. Questions starting ‘What?’ ‘Who?’ ‘Where?’ ‘When?’ are best. WAIT for an answer (at least 5 seconds) while F looks away and stirs their tea, studies the newspaper, looks in their bag for a tissue, etc.

- If C wants to whisper in P’s ear, or appears to be on the verge of speaking, P maintains eye contact with C and says “It’s OK to talk in front of F”.

- Smile and WAIT for an answer (at least 5 seconds).

- If no answer, P prompts C by offering an alternative, ‘X or Y?’, e.g. “Are you having coke or juice?” WAIT for an answer.

- If no answer, repeat the options, e.g. “Coke or juice?” Pause. Add “Or something else?” WAIT for an answer.

- If no answer, P says “Tell me in a little while” and carries on talking to F.

- If this doesn’t seem to be working, P says “You can tell me while F _____” (e.g. checks their phone messages/makes a drink/gets on with the crossword). This enables F to feign disinterest while P repeats the sequence.

- If C tries to pull P out of the room P says, “Don’t pull me, I’m having a nice time with F”. Then distract C, e.g. “Why don’t you go and get your ____?”; “Shall we look in the oven and see if the cakes are ready?”; “Could you go and pick me some mint please?”

- Stay calm and stick with it, after 10 minutes in the room with F, C’s anxiety will have dropped considerably!

- C may speak in a very quiet voice which is fine; do not ask C to repeat as their voice will get louder as they relax.

- C may feel more comfortable talking at the doorway at first, rather than in the room; this is again fine. They’ll come closer of their own accord.

4b. INTERACTING WITH FAMILIAR ADULT

A simultaneous target is for C to interact non-verbally with F, using eye contact, relaxed facial expressions and gesture:

- F shows interest in what C is doing or shares an activity. F chats away without expecting an answer in the style of a running commentary, leaving pauses so that C can comment if they feel ready: “You’re cutting out some really good shapes!”, “I wonder if that’s a flower… or maybe it’s a star…”.

- F can also direct questions via P, e.g. “I’d love to know what C’s favourite film is?” This provides the opportunity for C to respond, or for P to ask C the question following the above procedure ‘TALKING TO PARENT’. e.g. “C, what’s your favourite film?” C may then answer F via P.

5. TALKING TO FAMILIAR ADULT

When C can talk to P in front of F (4a), and engage with F non-verbally (4b), the next target is for C to answer F and eventually take the lead in conversation by making comments or asking questions:

- When C is happy, relaxed and occupied, F occasionally asks C questions by providing an alternative, X or Y: e.g. “C, I’ve forgotten your cat’s name, is it Lucky or Licky?” (it helps to be a bit silly!); “What Level shall we do now C, 2 or 3?” It helps to include C’s name so that C does not wait for P to answer, and to remind P not to inadvertently answer for C.

- WAIT. Allow plenty of time for C to answer (at least 5 seconds) and then repeat X or Y if necessary, e.g. “2 or 3?” Pause. Add “Or a different one?”

- WAIT again and don’t worry if C doesn’t answer. F smiles and says something like “I can see you’re thinking really hard about that” and moves on. F talks to P for a while before trying again.

- F repeats with more ‘X or Y?’ questions.

- After C has answered a couple of times, take a break – such a massive achievement can be exhausting for C.

- When C can answer ‘X or Y?’ questions easily, F asks ‘Wh___?’ questions, e.g. “Where do you keep your rabbits?”. WAIT…

− ‘What?’ ‘Who?’ ‘Where?’ questions are easiest as they can be answered with single words and short phrases.

− ‘When?’ is harder as it often requires a longer answer.

− ‘How’ and ‘Why’ should be avoided until later as these questions often require more explanation than C can manage initially.

− Be aware that ‘Which?’ can often be answered by pointing. - If no answer, F prompts C by falling back on an ‘X or Y?’ question, e.g. “Do they sleep outside or indoors?” WAIT for an answer.

- Hopefully natural conversation will follow if F shows an interest, e.g. by helping to clean out the rabbit hutch or asking C to show them how a phone App works. But a good way to help conversation along is by introducing games or activities where C needs to give F clues or ask F questions in order to reach a solution.

6. TALKING TO FAMILIAR ADULT ALONE

The final step is for C to talk to F without the comfort of P’s presence:

- As soon as C appears to be comfortable with F, P should be withdrawing for short periods, so that C and F are engaged in an activity without P. P can stay in the room but needs to concentrate on something else.

- Once C can talk to F, P must make excuses to leave the room for a while so that C does not have time to associate talking to F with P’s presence.

- On subsequent visits, P should always be present initially, but leave sooner and for longer until all C’s anxiety around talking to F has subsided.

GOOD LUCK!

Practice and memorise this sequence!

WAIT for C to speak…

If no response:

Rephrase question with an alternative, X or Y?

WAIT….

If no response:

Repeat “X or Y?” Pause. Add “or something else?” WAIT….

If no response:

Move on.

Gradually increase complexity of questions

EASIEST

Questions that can be answered ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ (can be answered by nodding or shaking head)

Which one? (can be answered by pointing)

‘What?’ ‘Who?’ ‘Where?’

‘When?’

‘How?’ ‘Why?’

Reasoning questions, e.g. ‘Can you explain…?’ ‘What’s the difference…?’

Personal questions, e.g. ‘How do you feel about…? ‘What do you make of that?’

HARDEST

Joining a Family where there is an SM Child

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

Joining a Family where there is a Child with Selective Mutism

This information sheet seeks to explain the nature of selective mutism (SM) and provides advice on how to build a happy and lasting relationship with children who suffer from this condition. The advice may initially seem to be counterintuitive but this in no way reflects upon you as a partner or parent. SM has been around for many years but only now is it becoming more widely understood.

Please do not under-estimate the value of your co-operation in following these guidelines. Your support will be a positive investment in both the future stability and cohesion of the family, and the prospective outcomes for the SM child.

Dos and Don’ts

Do…

- If your partner has explained that his/her child suffers from SM or if you suspect this to be the case, it is useful to do some further reading on the subject (see useful references below). Here you will learn that what may seem like stubbornness or deliberate behaviour is in fact an automatic anxiety reaction which the child cannot control. They are experiencing something very similar to stage-fright whenever they are expected to talk to or in front of certain people.

- You may initially get the impression that the child dislikes you – a selectively mute child that doesn’t speak, avoids eye-contact and never smiles, can easily give that impression! This is likely to leave you feeling hurt or even angry. It is important that you recognise that the child is simply reacting to the feelings of anxiety which they always get when meeting someone new. If they feel under pressure to speak they may even run away or hide in order to let their panic subside.

- Understand that it may take time to digest all this information which may go right against your natural instincts. But however hurt, helpless, angry or frustrated you may feel, it is vital that you do not show your true feelings. Any disapproval, disappointment or unreasonable demands will make it even harder for the child to relax and behave normally in your company.

- Be assured that the child’s inability to speak and interact freely with you is only a temporary setback, it will resolve with time, provided you are patient and tolerant.

Likewise your partner should explain to the child that talking and relaxing will get easier in time. You should reiterate this, and reassure the child that you understand their difficulties. - Remove all pressure on the child to speak until he or she is comfortable enough for this to happen naturally. You and your partner should continue to speak to the child and include him/her in all family activities as usual but avoid direct questions and make it clear that you are more interested in enjoying their company than hearing them speak. It is good to include siblings (when present) as this provides familiarity and may draw the child’s focus away from you, this will help the child get used to your presence.

- Always respond positively and warmly to any attempts by the child to communicate with you, either verbally or otherwise! Pointing nodding, drawing, listening to a story and sharing activities and are all valuable forms of communication, each a step nearer to talking.

- Whenever possible, please allow your partner and his/her child to take short breaks away from you and the company of others; this will allow the child to talk freely and convey urgent needs, without having to resort to whispering in your partner’s ear. This is particularly important when relatively long periods of time are spent in company.

- To begin with, please allow your partner to have some individual time with his/her child and siblings (if any). This will reduce the child’s anxiety on a regular basis and allow them to use a relaxed loud voice again. You will find that you can join in these sessions after a while if you use a step by step approach at the same pace as the child adapts to your presence – gradually get closer as the child continues to use a normal voice, and pull away as they get quieter.

- Please let your partner remain in charge of their child. The child will respond more quickly if your partner retains full responsibility for their day-to-day discipline and management. Handing over control to you is likely to significantly increase the child’s anxiety. This is true, no matter how well-meaning or competent your parenting skills are! SM is highly contextual in nature; an adult taking on the role of an authority figure tends to be more intimidating than one acting as a trusted friend, so it is important for you to concentrate on building a trusting friendship, rather than feeling pressured into quickly assuming a parental role.

- You or your partner should inform the child’s nursery or school about the change in family circumstances as this may influence his/her behaviour outside the home. SM children find all change difficult, even the little things in life, but with time to prepare, understand and adjust, they can happily adapt to a new situation.

Don’t…

- Do not feel your partner is being over-protective. It can seem as though your partner has chosen to side with the child; this is not the case. It is your support and co-operation that will ultimately help to forge a positive relationship with the child, and will draw the family closer together, in the long term.

- Don’t ask leading questions such as; “Why are you behaving this way?” “Why don’t you like me?”

Young SM children are unlikely to be aware of the concept of anxiety, so won’t to be able to explain their behaviour in terms of feeling anxious. In fact they are unlikely to be aware that their behaviour is odd at all! Behaviours such as avoiding eye contact, failure to speak and frozen facial expressions are instinctive reactions to anxiety provoking stimuli. There is no conscious thought involved, on the part of the child; in other words these behaviours are not premeditated! If you suggest that he/she dislikes you, it is likely to lead to confusion on the part of the child, he/she may simply agree with you because you’re an adult! - Don’t be pressured (or upset) by relatives or friends who advocate a zero tolerance, quick fix approach. SM is not widely recognised or understood by the public at large. so for those unfamiliar with the condition, it is tempting to think that it can be easily dealt with by confronting or correcting the child. As your new partner has probably discovered the hard way, this will only make matters worse! Any parent with experience of an SM child will tell you that patience and perseverance are required, over a prolonged period of time.

Useful references

- The free downloads section on: https://www.selectivemutism.org.uk/ especially the leaflets What is Selective Mutism? and Planning and Managing a Small Steps Programme.

- “The Selective Mutism Resource Manual” by Maggie Johnson and Alison Wintgens especially Chapter 2, Frequently Asked Questions, Chapter 6, Creating the Right Environment and Chapter 9, the Sliding-in Technique.

- ‘Silent Children – approaches to Selective Mutism’ – a DVD produced by SMIRA (Selective Mutism Information & Research Association) and obtainable from the online shop at www.selectivemutism.org.uk. Email enquiries may be made to info@selectivemutism.org.uk.

© Maggie Johnson and Vivienne Ponsonby for SMIRA 2010

Integrating a New Partner into a Family with SM Child

SELECTIVE MUTISM INFORMATION & RESEARCH ASSOCIATION

Registered Charity No. 1022673

Helping a New Partner join a Family where there is a child with Selective Mutism

Generally, children with selective mutism (SM) are most comfortable around those they have always lived with; this commonly includes parents, siblings and other familiar individuals who have always resided alongside the child – for example a live-in grandparent. Integrating a new, less familiar, adult into the home environment can therefore be problematic.

When in a comfortable, familiar environment (usually at home), children with pure SM will speak and interact in ways that are both age appropriate and characteristic of their own personality; however there is a discernible cut off point between the child’s immediate family and people outside their comfort zone. When people outside the child’s nuclear family enter the home, the child will tend to experience a marked rise in anxiety, this is when the characteristic symptoms of SM start to appear. Typically; the child appears more subdued than usual; facial expression may be frozen (unable to smile or react); there is a failure to speak (frequently, even when the child is spoken to); the child may markedly avoid eye contact; may become distressed; may fail to eat while being watched; may try to hide or avoid entering the room; may attempt to whisper to a familiar adult only. Young children may freeze completely when spoken to by an unfamiliar adult. All these responses can seem like rejection or dislike of the outsider if the child’s anxiety is not properly understood.

Integrating a new partner into a family which includes a child with SM can be particularly stressful, both for the child and main carer. In part, this can be because there is an expectation for that partner to assume a parental role and form a bond with the child as soon as possible. When this does not happen, frustration can build in both the natural parent and new partner which only feeds the child’s anxiety. If there is a concern or expectation that the child will be resentful of the new relationship the SM behaviour is likely to reinforce this belief and be mistaken for defiance. The natural parent’s attempt to explain the situation can appear at best over-protective and at worst, disloyal to the new partner.

Thus, successfully integrating a partner into a family with a selectively mute child can be a challenge! But if it is carried through in a sympathetic step-by-step fashion, a trusting relationship can be achieved.

Dos and Don’ts

Do…

- Explain in detail about your child’s condition and back this up with written information. Encourage your partner to go online or do some reading about SM (see useful references and website below).

- Remember that your partner may initially get the impression that the child dislikes him/her and may be feeling confused or disappointed; an selectively mute child that doesn’t speak, pointedly looks the other way and never smiles, may give that impression! It is important that you stress that the child is simply reacting to his/her feelings of anxiety.

- Understand that it may take time for your partner to digest all this information which may go right against their natural instincts. But however hurt, helpless, angry or frustrated they may feel, it is vital to remain calm. Any disapproval, disappointment or unreasonable demands will make it even harder for the child to relax and behave normally in their company.

- Remove all pressure on the child to speak until he or she is comfortable enough for this to happen naturally. You and your partner should continue to speak to the child and include him/her in all family activities as usual but avoid direct questions and make it clear that your new partner is more interested in enjoying their company than hearing them speak. It is good to include siblings (when present) as this provides familiarity and may draw the child’s focus away from your partner; this will ultimately help the child get used to their presence.

- Always respond positively and warmly to any attempts by the child to communicate either verbally or otherwise! Pointing, nodding, drawing, listening to a story and sharing activities and interests such as football, cycling, swimming etc.are all valuable forms of communication, each a step nearer to talking.

- Whenever possible, you and your child should take short breaks away from the company of others, this will allow him/her to talk freely to you and convey urgent needs, without having to resort to whispering in your ear. This is particularly important when relatively long periods of time are spent in company.

- At first, allow long periods of quality time together with your child, in the absence of your partner; this will reduce anxiety; allowing your child to return to his /her normal self and speak freely. Ideally your partner can gradually be included in these periods, first by occupying themselves nearby, then as an observer, and finally by taking part in your game or activity as the child gets used to speaking at normal volume in front of them.

- Reassure your partner that the child’s inability to speak and interact freely is only a temporary setback and with time, perseverance and patience the situation will resolve! Likewise, explain to the child that talking and relaxing will get easier in time.

- Do remain in charge of your child. Retain full responsibility for the day-to-day discipline and management of your child. Handing over control to your partner is likely to greatly increase your child’s anxiety. For many children, SM tends to be highly contextual in nature i.e. an adult taking on the role of an authority figure tends to be more intimidating than one acting as a trusted friend; that is why it is important for your partner to concentrate on building a trusting friendship, rather than quickly assuming a parental role, bearing in mind the child also has an absent father/mother with whom he/she may or may not have a talking relationship.

- Do inform your child’s nursery or school about the change in family circumstances; as this may influence your child’s behaviour outside the home. SM children find all change difficult, even the little things in life, but with time to prepare, understand and adjust, they can happily adapt to a new situation.

Don’t…

• Don’t feel that you have to choose between the child and your partner! Try and get your partner on side, his or her co-operation will ultimately bring the family closer together in the long term!

- Don’t ask leading questions such as “Why don’t you like John?”

Young SM children are unlikely to be aware of the concept of anxiety, so won’t to be able to explain their behaviour in terms of feeling anxious. In fact they are unlikely to be aware that their behaviour is odd at all! Behaviours such as avoiding eye contact, failure to speak and frozen facial expressions are instinctive reactions to anxiety provoking stimuli. There is no conscious thought involved, on the part of the child; in other words these behaviours are not premeditated! If it is suggested that the child dislikes someone, it is likely to lead to confusion on the part of the child, he/she may simply agree with you because you’re an adult! - Don’t be pressured and try not to be upset by relatives or friends that advocate a zero tolerance, quick fix approach. SM is not widely recognised or understood by the public at large, so for those unfamiliar with the condition, it is tempting to think that it can be easily dealt with by confronting or correcting the child. This will make matters worse as you will no doubt have discovered already! Any parent with experience of a selectively mute child will tell you that patience and perseverance are required, over a prolonged period of time.

Useful references

- The free downloads section on: https://www.selectivemutism.org.uk/ especially What is Selective Mutism? and Planning and Managing a Small Steps Programme

“The Selective Mutism Resource Manual” by Maggie Johnson and Alison Wintgens especially Chapter 2, Frequently Asked Questions, Chapter 6, Creating the Right Environment and Chapter 9, the Sliding-in Technique.

‘Silent Children’ DVD available from SMIRA https://www.selectivemutism.org.uk

‘My Child Won’t Speak’ – documentary made by Landmark Films, shown on BBC1, Feb 2010

© Maggie Johnson & Vivienne Ponsonby for SMIRA 2010

Transition Plan

TRANSITION PLAN

Preparing to change School, Class or Teacher or start at school or nursery

Time invested in agreeing and implementing a Transition Plan will ensure that the child adapts quickly to a new environment, builds on progress made and develops in confidence and independence.

A change of class and/or teacher can be a stressful time, particularly if a child is doing well and parents are afraid of losing momentum. However, if the transition is managed well, children can leave old memories and associations behind and gain confidence and independence in the new setting.

The following recommendations also apply to starting school or nursery for the first time.

1, It is vital that all staff in the new setting understand the nature and implications of selective mutism and that there will be no pressure on the child to speak until they are ready. Reassurance should be given to the child to this effect, both by parents and staff (see Phase 1 intervention for relevant information). Identify a learning mentor / keyworker / support teacher in the new setting who will provide an escape route if necessary and meet with the student regularly to ensure they are happy, not being teased/bullied etc.

2. Preparation should start several weeks in advance with positive comments about the move and familiarisation with the building, classroom and staff.

eg:

- social visits with parents for summer fair, concerts, charity events, play schemes etc

- look round school/class when building is empty (during holiday or after school)

- take photos and make a booklet about My New Class/School

- meet the head and classroom teacher/key staff in as informal a situation as possible.

- include younger siblings if available and appropriate.

- routine visit with current class plus one extra visit with familiar adult or friend

- new teacher/teaching assistant (TA) to visit child in current class or at home. (Home visits likely to be extremely beneficial – SMRM page 131).

- slide-in new teacher/TA before end of term (Phase 2 intervention)

3. If it is not possible to meet new staff in advance, try to ensure continuity by

eg:

- keeping the child with a best friend

- arranging for previous teacher/TA to spend some time with the child on their first day

- ‘borrowing’ previous keyworker to hand over to new keyworker at beginning of term (Phase 1 or 2 intervention)

- keeping current keyworker (but beware of child becoming too dependent on one adult over a long period of time)

4. It will be helpful if new teachers/teaching assistants (TAs) can make some time for a few minutes of rapport-building with the child on a one-to-one basis during their first week in order to achieve as many of the following as seem appropriate:

eg:

- reassure the child that they will not ask them questions or pick them for demonstrations unless the child volunteers